Just when you thought the Mortmain law was dead (Mississippi Baptist Foundation v. Fitch)

October 1, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

This is an unusual post. It is about a 2023 case dealing with Mississippi’s Mortmain law – a law that was repealed in the early 1990’s.

Reverend Harvey McCool died on August 31, 1969, survived by his wife Maggie McCool. In his will, he devised a mineral interest that he owned to the Mississippi Baptist Foundation (MBF), to be held in trust for his wife and his sister for their lives. At the death of his wife and sister, the MBF was to use the property “for the use and benefit of Foreign Missions carried on by, under the auspices of, or participated in by, the Mississippi Baptist Convention.”

Maggie died on April 17, 1973, with a will leaving her property to 3 children from a previous marriage (including the mineral interest). Reverend McCool’s sister died on February 5, 1986.

In December 2019, MBF filed a complaint in Amite County Chancery Court to probate Reverend McCool’s will and confirm title to the mineral interest. Because MBF was challenging the constitutionality of Mississippi’s Mortmain statute, the Attorney General, in addition to the heirs and successors of Maggie, were made parties to the suit.

The case was assigned to Chancellor Debbra K. Halford. The chancellor held that the Mortmain laws were constitutional, and that MBF was divested of any interest in the property in 1979 – ten years after the death of McCool.

MBF appealed and the case (Mississippi Baptist Foundation v. Fitch, 359 So. 3d 171 (Miss. 2023)) was decided by the Mississippi Supreme Court on March 16, 2023. The case was heard by a panel of Justices King, Chambelin, and Ishee. Justice King wrote the opinion for a unanimous court affirming Chancellor Halford.

The outcome in this case turns on the validity of Mississippi’s Mortmain law. These laws, which trace their origins to the Magna Carta, were designed to restrict the ability of organizations (explicitly including charitable and religious organizations) to hold property. In Mississippi, Mortmain laws date back to 1857. The 1890 constitution prohibited all testamentary devises to religious or ecclesiastical institutions. By 1940, the Constitution had been amended to provide that no person could devise more than one-third of their estate to “any charitable, religious, educational or civil institutions to the exclusion” of certain heirs, and also included the following restrictions: (1) any devise, regardless of amount, was invalid if devised less than 90 days before the death of the testator; and (2) the organization could only hold the property for 10 years after the death of the testator, and if the organization had not sold the property within 10 years, it reverted back to the estate of the testator. The loosening of the prohibition from 1890 to 1940 was to bring some balance – by continuing to protect against the concerns that the Mortmain law was designed to address while at the same time providing some ability for the testator to promote religious or charitable organizations.In 1987/1988 the Constitution and statute were amended again to make it clear that the ten year restriction begins to run “after such devise becomes effective as a fee simple or possessory interest.”

Thereafter, in 1992/1993 the Mortmain law – both the Constitutional provision and the related statutes were repealed.

It was the 1940 version of the Mortmain law that was in effect at the time of Reverend McCool’s death. Under that law, MBF could only hold the property in fee simple absolute for 10 years before it reverted back to Reverend McCool’s estate. MBF argued that McCool’s will devised a life estate to Maggie and McCool’s sister, and that MBF did not acquire a fee simple absolute interest – triggering the 10 year limitation – until 1986 at the death of McCool’s sister. And, MBF argued, since the Mortmain laws were repealed in 1992/1993 – their limitations did not apply when the 10 year reversion kicked in in 1996. In addition, MBF argued, if the Mortmain statute did apply, it was unconstitutional.

In a Court of Appeals case from 2012 (Hemeter Properties, LLC v. Clark, 178 So. 3d 730 (Miss. Ct. App. 2012)), the court held that, where a legal life estate was left to family members, with a remainder interest to a charitable organization, the 10 year time frame did not start until the family members died because the organization could only sell the property with the right of possession after the family member’s death.

The Court noted that this case was not like Hemeter. Here, the MBF owned the property as a trustee with the right to dispose of the property at any time (unlike Hemeter). Therefore, because MBF had the right to dispose of the property at the death of Reverend McCool, the ten years to dispose of the property began running at Reverend McCool’s death in 1969. MBF did not sell the mineral interest before 1979, therefore the property interest reverted to estate of Reverend McCool in 1979.

The Court refused to address MBF’s argument that Mississippi’s Mortmain law is unconstitutional – holding that MBF knew (or should have known) about the Mortmain statute issue at Reverend McCool’s death and waited more than 40 years to challenge the statute’s constitutionality. Therefore, MBF was barred both legally (under the statute related to claiming an interest in land) and equitably (failure to act timely to protect their rights) from making a constitutional argument.

Professor Thoughts

One thing I always tell my students in Wills & Trusts and Property Law classes is how far reaching their representation can be. Mistakes in property transfers (either by deed or by will) may not be recognized until years later. This case is certainly an example of that. I only teach Mortmain statutes in passing, because they have been repealed or declared unconstitutional in almost all jurisdictions today.

Because a number of lawyers practicing today have probably never studied (or perhaps heard of) Mortmain laws, I thought a short discussion would be worthwhile. If nothing else, this should get you a point if this is the answer to a trivia question.

The Statutes of Mortmain were first enacted in the late 1200’s during the reign of Edward I. The goal was to prevent land from passing into the hands of the church and out of the taxing authority of the crown. This was the same justification for enactment of Mortmain laws in the United States – taking property permanently out of the stream of commerce and the taxing authority of the state.

This was not the only justification, however. There was also the concern that a testator who is near death could be in a position to be unduly influence by charitable organizations – leveraging the testator’s fear of death to secure a bequest. Hence, Mississippi’s 1940 version of the law which invalidated bequests made within 90 days of death.

A final justification (and this is my favorite) is to prevent a testator who was not charitable during life to be charitable at death at the expense of their family. Mississippi’s law reflected this by restricting the amount that could be devised to no more than one-third of the testator’s estate.

It might be worthwhile setting out the constitutional challenges to the Mortmain statute argued by MBF. While the Supreme Court did not address these arguments, other states have invalidated their Mortmain statutes based on constitutional challenge.

The essential argument is that Mortmain laws violate the Equal Protection Clause because they are not able to survive rational basis review. Specifically, MBF’s brief argues that the purpose of the Mortmain laws are to prohibit the testator from being unduly influenced by the named organizations and they are not rationally related to that goal because:

- They do not take into account the susceptibility of the individual testator to undue influence or whether the testator was actually in their last illness at the time the bequest was made;

- They do not take into account whether the testator has close family that need to be protected from overreach;

- They do not take into account the fact that others are in “an equal position to improperly influence the testator, including lawyers, doctors, nurses, clergymen, caretakers, housekeepers, companions, and the like” and there is no reason to believe that religious or charitable organizations are more “unscrupulous than greedy relatives, friends, or acquaintances”;

- The statutes do not address inter vivos gifts and non-charitable gifts that have the same potential for overreaching.

To the extent that a proper case comes forward, these arguments remain valid arguments against the Mortmain law. It should be noted, however, that there are counter arguments. For example, the fact that the charity could sell the property within 10 years and not lose the value of the bequest could save the statute if a valid challenge is ever raised.

Keeping the faith – state of mind in an adverse possession case

September 27, 2024 § 1 Comment

By: Donald Campbell

Signaigo v. Grinstead, 2024 WL 2284923 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024)

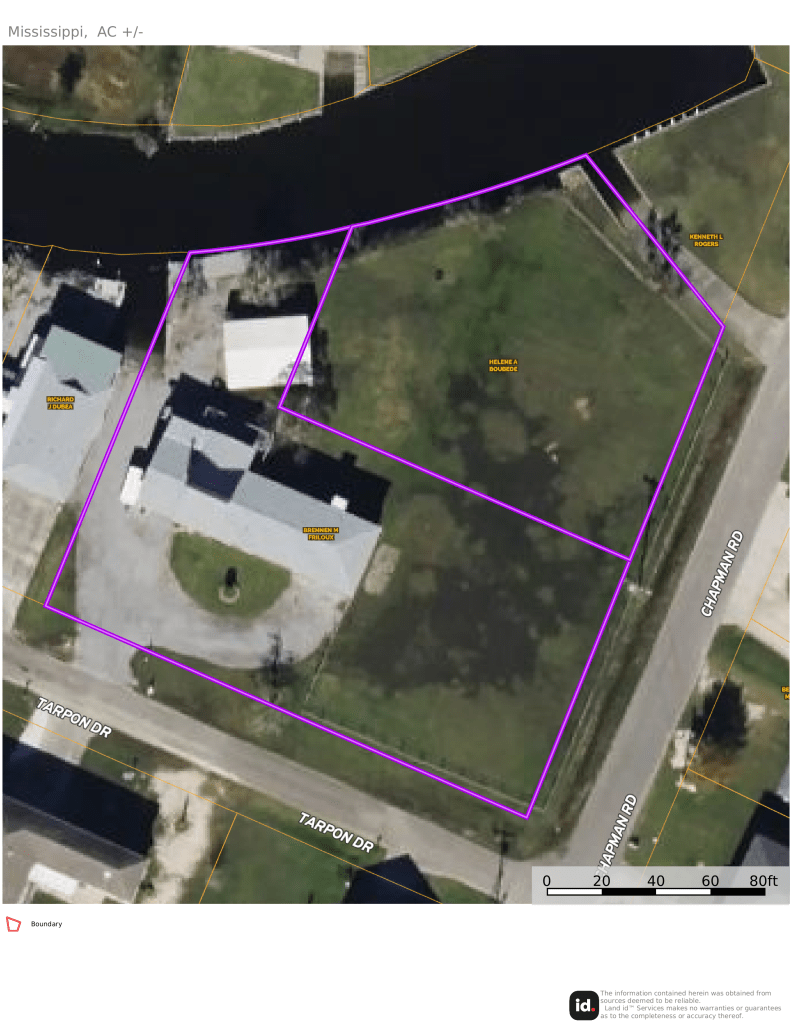

William and Judith Signaigo purchased property in Shorelines Estates in Hancock County in 1997. The adjacent property was owned by Helene A. Boubede at that time. Boubede lived in Iowa and, when she died, the property went to her daughter Myrna Grinstead.

After moving onto the property, the Signaigos fenced in part of their property and all of the Boubede property. When asked if she gave any thought as to whether they were fencing in someone else’s property, Mrs. Signaigo testified: “No. The only thing I was concerned about was the fact that there’s water here and there is a street there and the dogs were bringing stuff back from other places and we wanted to fence it in.” She also testified that she and her husband knew that the property was not theirs. In fact, they tried to contact Ms. Boubede about purchasing the property but were not able to get in contact with her. Beginning in 1997, the Signaigos performed all upkeep on the disputed property: mowing the grass, removing debris following hurricanes, removing trees, and providing fill material.

On September 15, 2021, the Signaigos filed a lawsuit against Boubede/Grinstead claiming ownership of the property by adverse possession. The case was assigned to Chancellor Margaret Alfonso. After a hearing, the chancellor found that adverse possession had not been established because the the Signaigos did not establish: (1) claim of ownership of the property; or (2) open and notorious possession. Signaigos appealed and the case was assigned to the Court of Appeals.

Judges Barnes, Greenlee, and McCarty were on the panel that heard the case. Judge Greenlee, writing for a unanimous court, affirmed Chancellor Alphonso.

To establish a claim of ownership by adverse possession in Mississippi the adverse possessor must satisfy the following six elements for 10 years (see Miss. Code Ann. 15-1-13): (1) under claim of ownership; (2) actual or hostile; (3) open, notorious, and visible; (4) continuous and uninterrupted for 10 years; (5) exclusive; and (6) peaceful.

The dispositive issue was whether there was a “claim of ownership.” There have been a split of decisions in Mississippi when it comes to what it means to claim ownership. Some older cases have said that the key to a claim of ownership is the taking of steps demonstrating that the adverse possessor is making a claim to the property. Therefore, the determining factor was what the adverse possessor did to possess the property — not the state of mind of the adverse possessor. For example, in 1846, the High Court of Errors and Appeals of Mississippi held: “There is no doubt, that the possession of a mere intruder, is protected to the extent of his actual occupation; whilst one who has color of title is protected to the extent of the limits of his title.” (Grafton v. Grafton, 16 Miss. 77, 91 (Miss. 1846)). Again, in Levy v. Campbell in 1946, the court notes that, as far back as 1858: “it has been settled rule in this state that although the possession may have been begun by a mere intruder without any color of title at all, the occupant may establish title by adverse possession to the extent of his actual occupation.” In short — it does not matter that the adverse possessor knows that they are trespassing so long as they actually take possession.

A 2004 Mississippi Supreme Court case (Blackburn v. Wong, 904 So. 2d 134 (Miss. 2004)) rejected the idea that possession is all that matters and required the adverse possessor to be acting in good faith. “Good faith” means that the adverse possessor must have a reasonable belief that they have rights in the property. In Blackburn a lawyer built a law office onto the property of another. Shortly after the building was constructed, a surveyor informed the lawyer that his office was across the property line. At that point the lawyer testified he had three options: (1) contact the true owner to try to purchase the property; (2) dig up the sewer lines and tear down the building; or (3) wait for the adverse possession time to pass and claim ownership. The lawyer chose to wait out the time for adverse possession. The lawyer possessed the property from 1971 through 1999 (when the suit commenced). The court, without much analysis held that, because the lawyer found out that he did not own the disputed strip shortly after the building was completed, he could not claim the property by adverse possession.

Relying on the Blackburn holding, the court in Signaigo held that, because the Signaigos knew that they did not own the property at the time they went into possession, they could not establish the element of “claim of ownership”. Therefore, the heirs of Boubede own the disputed parcels. The court remands the case for a determination of heirship.

Professor Thoughts

The justification of allowing adverse possession is to ensure that property is used and not abandoned by an absentee owner without any hope of putting the property back into use. To this end, there are three approaches that states have taken to determine whether an adverse possessor can demonstrate a “claim of title”: (a) good faith; (b) bad faith; and (c) objective approach (state of mind is irrelevant).

The majority of states take the approach that the state of mind is irrelevant. The rationale for taking this approach is two-fold: (1) if the justification of adverse possession is to reward the industrious possessor and punish the true owner who has not bothered to check on their property for more than 10 years — whether the adverse possessor knew the property was not theirs or whether they had a reasonable belief it was, is irrelevant; and (2) requiring testimony of a state of mind can encourage adverse possessors to lie on the stand to conform their testimony to what is required in the jurisdiction. Those older Mississippi cases followed this approach — emphasizing the possession over the state of mind. In adopting the objective approach (and abandoning the good faith approach), the Washington Supreme Court noted: “The doctrine of adverse possession was formulated at law for the purpose of, among others, assuring maximum utilization of land, encouraging the rejection of stale claims and, most importantly, quieting titles… Because the doctrine was formulated at law and not at equity, it was originally intended to protect both those who knowingly appropriated the land of others and those who honestly entered and held possession in full belief that the land was their own… Thus, when the original purpose of the adverse possession doctrine is considered, it becomes apparent that the claimant’s motive in possessing the land is irrelevant and no inquiry should be made into his guilt or innocence.” (Chaplin v. Sanders, 676 P.2d 431, 435 (Wash. 1984)(en banc))

Some states (after Wong, Mississippi is in this category) require that the adverse possessor act in good faith (have a reasonable belief that they own the property to satisfy the claim of ownership requirement). The justification for this approach (and this is apparent in both the Wong and Signaigo case) is the refusal to reward land pirates (ie intentional trespassers). Under this approach, it does not matter that the Signaigos put the property to use from 1997 until 2021 or that Blackburn had his law office on the property from 1971 until 1999 — the fact that they were using the property knowing it was not theirs, defeated their claim.

The final approach, bad faith, is only followed by one state that I am aware of — Arkansas (Fulkerson v. Van Buren, 961 S.W. 2d 780 (Ark. Ct. App. 1998)) Under this approach, to satisfy the “claim of ownership” element, the adverse possessor must be able to show that they knew that the property was not theirs and they intended to claim it as their own. The rationale is that someone should not be able to gain title (and the owner should not lose title) by accident. To claim title by adverse possession, the possessor must intend to do so.

The bottom line: in an adverse possession case, the adverse possessor must be able to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that they had a good faith belief they had a right to the disputed property. This should not be a problem in a run-of-the-mill boundary line dispute case where the parties genuinely did not know about the encroachment until it is revealed years later (for example Conliff v. Hudson, 60 So. 3d 203 (Miss. Ct. App. 2011)). However, a client who has long possessed the property and either knows they have no ownership interest in the property or learn, before the 10 years runs, that they are not the owner of the property, will not be able to establish the “claim of title” element of adverse possession.

Posthumously Conceived children

September 24, 2024 § 1 Comment

With advances in technology, babies can now be created without sexual intercourse. The use of assisted reproductive technology has been increasing. In 2021, 2.3% of infants born in the United States were conceived with assisted reproductive technology. Under traditional law, if a child was not in utero at the time of the parent’s death – they were not considered the child of the deceased. Today, however, a deceased person can be the biological parent of a child long after their death.

Children conceived by assisted reproductive technology raise unique challenges for the traditional inheritance system. First, the parent who predeceased before the child was conceived may have no knowledge that their biological material would be used to assist in reproduction, and therefore may not want the after born child to have a share of their estate. Second, any inheritance that is provided for the child will diminish the amount that is taken by children who were born or conceived prior to the parent’s death, and could disrupt the orderly administration of the estate if there are no limitations on how long after the parent’s death a child can be conceived.

The issue is how to balance the competing concerns between the innocent child, the deceased’s interest in controlling where their property goes, and the efficient administration of estates. It should be noted that the outcome impacts issues beyond the inheritance system itself. Survivorship rights are often determined by whether the person has the right to inherit under a state’s descent and distribution law. The Social Security Administration considers a posthumously conceived child as a non-marital child who is only entitled to benefits if they are entitled to inheritance rights under state intestacy law.

In 2024, Mississippi adopted House Bill 1542 that sets out the rights of children conceived by assisted reproductive technology (methods of conception without sexual intercourse). The law provides that children born through assisted reproductive technology can inherit a child’s share of the deceased parent’s personal property if certain procedures are followed. The law is tilted the Chris McDill law in memory of Chris McDill. McDill was diagnosed with cancer and he and his wife Katie were unable to conceive before his death. Katie subsequently had a child through IVF, but was not able to claim survivor benefits through the Social Security Administration because the child was not entitled to inherit under Mississippi law.

First, the parent must have died without disposing of all of their personal property. Therefore, a posthumously conceived child’s rights are solely in personal – not real – property. Furthermore, if the deceased has disposed of all of their personal property in a will to someone other than the posthumously conceived child – the subsequently born child is not entitled to inherit.

Next, there must be a document signed by the deceased parent and the person that is planning on using the genetic material that the now-deceased parent consented to the use of genetic material in assisted technology after their death. The requirement that there be a record of consent from the deceased parent is to recognize and respect the reproductive desires of the deceased.

After death, the personal representative and the court must have been given notice or had actual knowledge of the intent to use genetic material in assisted reproduction not later than six months after the death of the parent. Thereafter, the embryo must be in utero not more than thirty-six months after the parent’s death, and the child must be born not later than forty-five months after the parent’s death and must live 120 hours after birth. The purpose of setting this time frame is to give the surviving parent an opportunity to grieve and contemplate whether to use the genetic material while, at the same time, ensuring that the estate will not remain open indefinitely.

If the deceased was divorced or legally separated from the individual seeking to use the genetic material, there is a rebuttable presumption that the decedent did not consent to use of their genetic material in assisted reproductive technology.

If the requirements above are satisfied, the court shall set aside a child’s share of the qualifying personal property. Each qualifying child would share in that child’s share of the estate. The court should then distribute the remainder of the estate as provided by law of descent and distribution and close the estate for all purposes except distribution of the set-aside property. Once the eligible children (born and survive 120 hours) are ascertained, the court should distribute the set-aside property to those children. If there are no eligible children, the court should distribute the estate according the descent and distribution statute. The statute expressly provides that it is the intent of the law that “an individual deemed to be living at the time of the decedent’s death” under the statute would qualify for federal survivor benefits.

Your eyes are not deceiving you

September 20, 2024 § 27 Comments

My name is Donald Campbell. I am a professor at Mississippi College School of Law where I teach in the areas of Property, Wills & Trusts, and legal ethics. When I first started teaching Wills a colleague told me that I had to subscribe to Judge Primeaux’s blog. I did, and thereafter I looked forward to every post that he made. And it was not just me. There is no doubt that Judge Primeaux’s blog was a go-to for all things chancery (and beyond) for years. When Judge Primeaux decided to step away from blogging it was a loss for the profession.

I am excited to announce that with the judge’s blessing, I am hoping to bring back a version of Better Chancery Blog. The focus will still be on issues/cases that arise in chancery court. Of course the problem is that I can never produce the “my thoughts” comments that pulled back the curtain on how a judge thinks. I am hoping that, through the comments members of the bar and bench can engage in a discussion of how these issues arise in practice.

Although I realize I am burying the lead, I am truly honored to have Dean Debbie Bell as a contributor to the blog on family law issues. Dean Bell needs no introduction. Her book (Bell on Mississippi Family Law) is a well-respected and often-cited treatise on family law in Mississippi. I am excited to see the insight that Dean Bell will bring to the blog.

To give you a sense of how the blog will operate going forward, I hope to post twice a week. A post on Tuesday that covers a recent issue or case. Then a post on Friday that looks at a case or issue that may not be directly related to current issues in Mississippi law. If there are any suggestions on improving the blog as we move forward, please to not hesitate to reach out.

June 15, 2020 § 30 Comments

As I mentioned here before, today’s is the final post on this blog, except as I mention below.

All of the content posted up to now will remain at this address for your ready access unless WordPress changes the rules to something intolerable, in which case I will try to let you know before disappearance takes place.

Please remember that the law changes all the time, so when you read that post from 2012 and think “Aha! Just the case I’ve been looking for!” it may be that it is no longer good law. This site has never been intended as a substitute for solid research.

Several people have asked me to replace my 4x/week posts with occasional pieces. Well, that would be more of a nuisance to readers trying to keep up than something helpful. I may share some of my photos from time to time. I’m no Ansel Adams or William Eggleston, or even Vivian Maier, but I do enjoy my cameras and I enjoy sharing my pictures.

There is a move afoot to create a chancery practice site. I don’t know whether it will be a static site, or a blog, or what form it ill take, but if you will support it, you will benefit.

More than 65% of my life has been dedicated to the law, the past 14 as chancellor. Despite all its shortcomings, I think the law is the noblest profession. My passion as judge has been to heighten professionalism and the level of practice. I hope this blog served that purpose.

So, thank you for letting me try to enlighten and entertain you these past ten years. It’s been an enjoyable experience. I have enjoyed getting to meet in person and by comment many lawyers I would never have crossed paths with otherwise.

The Value of Valuation

June 11, 2020 § Leave a comment

In the divorce case between Missy and Randy Norwood, the only evidence in the record of property values was in the form of the parties’ 8.05 financial statements. This despite the fact that the property in dispute for equitable division included 129 acres of land with poultry houses, a residence with 3.37 acres and the poultry business. Missy’s financial statement assigned a gross value of $1,148,000, and Randy’s total was $840,000. There was debt. The chancellor sorted through it as best he could, assigned values, and divided the estate. Unhappy with the division, Missy appealed.

The COA affirmed in Norwood v. Norwood, decided May 12, 2020. Judge McCarty wrote the 5-4 majority opinion:

¶11. “It is within the chancery court’s authority to make an equitable division of all jointly acquired real and personal property.” Martin v. Martin, 282 So. 3d 703, 706 (¶7) (Miss. Ct. App. 2019) (quoting Bullock v. Bullock, 699 So. 2d 1205, 1210-11 (¶24) (Miss. 1997)). “This Court reviews a chancery court’s division of marital assets for an abuse of discretion.” Id. “We will not reverse a chancery court’s distribution of assets absent a finding that the decision was manifestly wrong, clearly erroneous, or an erroneous legal standard was applied.” Id.

¶12. “Our Supreme Court has held that the foundational step to make an equitable distribution of marital assets is to determine the value of those assets.” Id. at (¶8) (internal quotation mark omitted). From there the chancery court must equitably divide the marital property according to the factors first articulated in Ferguson. Id. at 706-07 (¶8). [Fn omitted]

¶13. Now on appeal, Missy claims error in the chancery court’s valuation of the marital assets. However, the chancery court relied upon the evidence provided by the parties in valuation and distribution. The general rule is that “[i]t is incumbent upon the parties, not the chancery court, to prepare the evidence needed to clearly make a valuation judgment.” Id. at 707 (¶10). In Martin, the wife had complained that the husband received more than her after the chancery court’s distribution of assets. Id. at 706 (¶6). Yet, “[d]espite numerous requests from the chancery court, neither party provided the court with a single valuation of the assets at issue,” “[t]here was no testimony of the market value of the real property,” and “[a]ppraisals were never conducted.” Id. at 707 (¶9).

¶14. In light of the general rule, we affirmed the court’s decision regarding property distribution. Id. at (¶13). For “[w]here a party fails to provide accurate information, or cooperate in the valuation of assets, the chancery court is entitled to proceed on the best information available.” Id. at (¶10); see also Messer v. Messer, 850 So. 2d 161, 170 (¶43) (Miss. Ct. App. 2003) (“This Court has held that when a [chancery court] makes a valuation judgment based on proof that is less than ideal, it will be upheld as long as there is some evidence to support [its] conclusion.”).

¶15. In this case, the chancery court considered all of the evidence before it—both parties’ Rule 8.05 financial statements and their in-trial testimony. It is clear that more and better proof would have been helpful to the chancery court. But the fact that there was little proof does not automatically warrant a reversal of the chancery court’s determination of this issue. As we declared nearly two decades ago, “[t]o the extent that further evidence would have aided the chancellor in these decisions, the fault lies with the parties and not the chancellor.” Ward v. Ward, 825 So. 2d 713, 719 (¶21) (Miss. Ct. App. 2002).

¶16. The dissent cites Mace v. Mace, 818 So. 2d 1130, 1133-34 (¶¶13-14) (Miss. 2002), to suggest we should remand due to the lack of an expert’s valuation of the marital property. In that case, the Mississippi Supreme Court reviewed the valuation of a medical practice, which the trial court had assessed at $374,000, including the value of the building and equipment. Id. at 1133 (¶13). Because of the complexity of the issues, and because “it [was] abundantly clear from the testimony that the valuation of the practice was unreliable,” the Supreme Court reversed and remanded for a more comprehensive valuation. Id. at 1134 (¶¶15-16).

¶17. However, Mace did not create a requirement that only an expert can conduct a property valuation before an equitable division can be determined. Parties may choose not to hire an expert or not have the resources to do so. Unlike the complex proof needed in Mace, this is not a case that requires clarification on remand. The chancery court was not impeded in this matter because of the proof presented at trial. The chancery court found that “Randy’s 8.05 Financial Statement shows minimal income from the poultry operations” and that both Randy and Missy agreed the expenses he listed from the poultry farm were accurate. There is no reason to re-try this case when there is “minimal income” and the expenses were not in dispute.

¶18. Because it is the parties’ duty, and not the chancellor’s, to prepare and submit evidence for a valuation judgment, we find no abuse of discretion. It is clear that the chancery court’s decision was based upon the proof mustered by the parties at trial. It was the parties’ decision at trial to present slim proof. That choice will not result in reversal on appeal. This decision is affirmed.

As the court points out in ¶17, there are legitimate reasons why parties may choose not to have property appraised by a professional. Cost most certainly can be a factor. The parties may simply choose to leave it up to the chancellor to decide, although that is usually a crap shoot.

You can use requests for admission to help nail down values.

Just remember that the less precise your proof the more the matter falls within the chancellor’s discretion and judgment. And if there’s any proof at all in the record to support her findings, your chances of getting her reversed are practically nil.

Reprise: The Vital Importance of Checklists

June 10, 2020 § 1 Comment

Reprise replays posts from the past that you might find useful today.

Trial Factors aka “Checklists”

March 6, 2018 § Leave a comment

The MSSC threw down the gauntlet in 1983 in Albright v. Albright, mandating that trial judges must make findings of fact as to certain specific factors when making an award of child custody.

Since then, the number of factor-driven cases has multiplied. There are 13 now, by my count.

I call it “Trial by checklist” because you can reduce every list of factors to a convenient checklist that you can use at trial. I suggest you copy these checklists and have them handy in your trial materials. Build the outline of your client’s case around them. In your trial preparation design your discovery to make sure that you will have proof at trial to support findings on the factors applicable in your case. Subpoena the witnesses who will provide the proof you need. Present the evidence at trial that will support the judge’s findings.

If you don’t put on proof to support findings of fact by the chancellor, your case will fail, and you will have wasted your time, the court’s time, your client’s money. You will have lost your client’s case and embarrassed yourself personally, professionally, and, perhaps, financially.

If the judge fails to address the applicable factors in his or her findings of fact, file a timely R59 motion asking the judge to do that, because failure to make findings with respect to the applicable factors is cause for remand — an expensive do-over. But remember — and this is critically important — if you did not put the proof in the record at trial to support those findings, all the R59 motions in the world will not cure that defect.

Here is an updated list of links to the checklists I’ve posted:

Income tax dependency exemption.

Modification of child support.

Periodic and rehabilitative alimony.

I try to remind folks twice a year about the importance of using checklists in making your cases.

Constructive Desertion

June 9, 2020 § Leave a comment

It’s not often that constructive desertion cases come around, particularly on appeal, so when one does, it is noteworthy.

Kevin Watson claimed that his wife Carole was guilty of constructive desertion of him, entitling him to a divorce. Following a trial, the chancellor agreed and granted Kevin a divorce on that ground. Carole appealed.

In Watson v. Watson, decided June 2, 2020, the COA reversed and rendered. Here is how Judge McDonald’s opinion for an 8-0 court (Barnes not participating) addressed the issue:

¶8. The chancellor found that Kevin was entitled to a constructive-desertion divorce because “many instances [of Carole’s behavior] rise to the requisite level of conduct.” In so doing, the chancellor mentioned one specific incident that occurred during Kevin and Carole’s March 2013 trip to the British Virgin Islands. Otherwise, the chancellor found that Kevin was entitled to a constructive-desertion divorce due to “Carole’s combative public outbursts” and “Carole’s constant, and in many cases, irrational accusations against Kevin.”

¶9. The Mississippi Supreme Court has held that a constructive-desertion divorce is available under the following limited circumstances:

If either party, by reason of such conduct on the part of the other as would reasonably render the continuance of the marital relationship unendurable, or dangerous to life, health[,] or safety, is compelled to leave the home and seek safety, peace[,] and protection elsewhere, then the innocent one will ordinarily be justified in severing the marital relation and leaving the domicile of the other, so long as such conditions shall continue, and in such case the one so leaving will not be guilty of desertion. The one whose conduct caused the separation will be guilty of constructive desertion[,] and if the condition is persisted in for a period of one year, the other party will be entitled to a divorce.

Benson v. Benson, 608 So. 2d 709, 711 (Miss. 1992) (quoting Day v. Day, 501 So. 2d 353, 356 (Miss. 1987)). Said differently, “constructive desertion occurs when the innocent spouse is compelled to leave the home and seek safety, peace, and protection elsewhere because the offending spouse has engaged in conduct that would reasonably render the continuance of the marital relation, unendurable or dangerous to life, health or safety.” Hoffman, 270 So.

3d at 1126-27 (¶24) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Griffin v. Griffin, 207 Miss. 500, 505, 42 So. 2d 720, 722 (1949)). [Fn 2] “Chancellors should grant a divorce on the ground of constructive desertion only in extreme cases.” Id. at 1127 (¶24).

[Fn 2] “The line between . . . constructive desertion and . . . habitual cruel and inhuman treatment is blurred . . . .” Hoskins v. Hoskins, 21 So. 3d 705, 710 (¶21) (Miss. 2009). “[T]he only distinction” is that in a constructive-desertion case, one spouse “is compelled to leave and the [other spouse’s] objectionable conduct continues for a year.” Id.

¶10. The case is not one of those extreme circumstances. One basis the chancery court used to grant Kevin a divorce occurred in March of 2013. Kevin testified that Carole must have drugged him one night during their trip to the British Virgin Islands “[b]ecause one minute [he] was fine, and the next minute [he] wasn’t[,]” and Carole “always had Xanax and the drugs that she got . . . from her psychiatrist.” Although Kathy Boyd, who was among the four other people on the trip, said she “felt like Kevin had been given something” because his state was inconsistent with the alcohol that he consumed, neither she nor Kevin testified that they saw Carole put anything in Kevin’s drink. [Fn 3] There was also testimony in the record that both Carole and Kevin often drank to excess.

[Fn 3] Although Kevin also testified that “there were other instances . . . where that very same scenario took place . . . ,” he did not elaborate regarding when or how often those “other instances” occurred.

¶11. In addition to the insufficient evidence that Carole “drugged” Kevin on the trip, the March 2013 incident did not cause Kevin to leave the marital home. He continued to live there after the trip. Kevin did not tell Carole that he wanted a divorce until December 2013 and did not leave the marital home until approximately a month later. Thus, Kevin endured the supposedly unendurable marriage for approximately ten months after the incident in the British Virgin Islands.

¶12. As for Carole’s “combative public outbursts,” the evidence shows that during the seven years of their marriage, Carole once yelled at a restaurant staff, yelled at two women who cut past her in a line at a concert, and that she blurted out private marital details during a September 2013 dinner with friends. Again, however, this does not constitute substantial credible basis to conclude that Kevin was compelled to leave the marital home.

¶13. Kevin testified that the marriage first became unendurable for him during the summer of 2009 when Carole failed to adequately take care of herself, him, and the marital home. Those were three provisions of their unwritten four-point agreement that they purportedly entered when she stopped working in the latter part of 2007. Kevin also said that the marriage was unendurable because he and Carole “can’t stand to be in the same room together. I mean, it’s just unhealthy [and] . . . stressful. It’s depressing.” But Kevin continued to live with Carole for years thereafter.

¶14. As previously mentioned, our supreme court has commanded that constructive desertion divorces are available only in “extreme” circumstances. Lynch v. Lynch, 217 Miss. 69, 81, 63 So. 2d 657, 661 (1953). In one case, a constructive-desertion divorce was upheld where a wife ignored her blind husband’s protests and frequently left him at his relative’s house for days, left him without food during the week, and allowed her disrespectful grandson to live in the marital home for three years against his protests. Deen v. Deen, 856 So. 2d 736, 737 (¶¶4-6) (Miss. Ct. App. 2003). A constructive-desertion divorce was also available when a husband was subjected to his wife’s false accusations of adultery several times a week for approximately ten years. Lynch v. Lynch, 616 So. 2d 294, 295-97 (Miss. 1993). But a constructive-desertion divorce is not a remedy when a husband merely says there is “no marriage” and “no relationship,” and he began having an affair nearly one year before he left the marital home. Grant v. Grant, 765 So. 2d 1263, 1267 (¶¶10-11) (Miss. 2000). [Fn 4]

[Fn 4] The chancellor acknowledged that Kevin and another woman had been involved in a clandestine and emotionally romantic relationship for several months before Kevin told Carole that he wanted a divorce. Their relationship became physical approximately two weeks after Kevin finally left the marital home. Kevin did not disclose his relationship to Carole before he left, but she discovered it a few months later. The chancellor did not find that Kevin left Carole because he preferred to be with his paramour.

¶15. After a thorough review of the transcript and record, it is clear that Kevin became increasingly unhappy in the marriage because he felt as though Carole was not fulfilling her marital obligations to take care of herself, him, and the domestic sphere of the relationship. Carole certainly leveled many accusations against Kevin that were not borne out by the record. Suffice it to say, there was clearly a significant amount of mutual animosity by the time of the divorce trial years later. But it would be unreasonable to find that Kevin’s abandonment of the marital home was the natural consequence of an alleged incident on a trip they took months earlier. See Griffin, 207 Miss. at 504, 42 So. 2d at 722. And it was undisputed that Kevin remained in the marital home for still another month after he told Carole that he wanted a divorce.

¶16. Notwithstanding the clearly acrimonious feelings between Carole and Kevin, the substantial credible evidence shows that “this case is yet another in our developing litany where . . . the problem [in the marriage] is [the couple’s] fundamental incompatibility.” Day, 501 So. 2d at 355. As such, this is not one of the “extreme cases” contemplated by our supreme court. It follows that we are compelled to reverse the chancellor’s judgment.

The main takeaway here is that constructive desertion is no easy path to a divorce. Not only must you make an “extreme case,” but you also have to prove the elements of desertion, about which I posted at this link. And don’t forget that the burden of proof is by clear and convincing evidence (HCIT is the only ground that requires only a preponderance of the evidence).

I’m still unsure why we don’t have some kind of incompatibility or separation ground for divorce. The argument I often hear against is that those would open the floodgates of divorce in Mississippi. That presumes that our restrictive laws are keeping those floodgates closed, which I perceive not to be the case at all. Every family-law practitioner in this state knows that our current statutory scheme fosters and even encourages “divorce blackmail,” which often results in inequitable and unfair settlements. I’m not sure that the state truly has a legitimate interest in preserving unhappy, unhealthy, and even dangerous marriages.

MSSC Clarifies the Relationship Between Alimony and Social Security Benefits

June 8, 2020 § Leave a comment

Before 2018, the rule in Mississippi was that an alimony payor was entitled to a dollar-for dollar credit against an alimony obligation for derivative Social Security (SS) retirement benefits received by the payee ex-spouse. Spalding v. Spalding, 691 So.2d 435 (Miss. 1997).

Note: Derivative benefits are those derived from the payor’s SS entitlement, as where the payee elects to base benefits on the spouse’s earning record instead of his or her own, so as to receive a greater benefit.

That changed with the case of Harris v. Harris, 241 So.3d 622, 628 (Miss. 2018), which overruled Spalding and held that derivative SS benefits do not trigger an automatic modification of alimony, but that the trial court must “weigh all the circumstances of both parties and find that an unforeseen change in circumstances occurred to modify alimony.”

Then, in Alford v. Alford, decided July 23, 2019, the COA reversed and remanded a chancellor’s award of alimony because it did not take into account Linda Alford’s inevitable receipt of derivative SS benefits in its initial determination of alimony. The COA remanded the case to the trial court, but Linda filed a petition for certiorari with the MSSC.

The MSSC granted cert., and in Alford v. Alford, decided June 4, 2020, the court reversed the COA in part. At ¶2, the court’s opinion states:

“We granted certiorari because this Court has not answered whether a chancellor should consider Social Security benefits when considering initial alimony awards. We find that consideration of derivative Social Security benefits should be reserved for alimony modification proceedings.”

Justice Kitchens wrote for the unanimous court:

¶14. The Court of Appeals held that the chancellor should have considered Linda Alford’s near-future reception of derivative Social Security benefits when it made her initial alimony award because “Harris specifically holds that derivative Social Security benefits will not justify a subsequent modification of alimony if the benefits were anticipated or foreseeable at the time of the divorce.” Alford, 2019 WL 3297142, at *6 (citing Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628-29).

¶15. Linda Alford argues that the Court of Appeals erred in its interpretation of Harris. According to her, Harris concerned “whether the other financial circumstances of the parties had materially changed so as to warrant a modification of alimony, when coupled with the advent of Social Security benefits” and did not concern whether derivative Social Security benefits were foreseeable. This Court agrees. Harris did not hold that the future receipt of derivative Social Security benefits is a foreseeable circumstance that would not allow a subsequent modification of alimony; rather, Harris said that when an alimony recipient acquires derivative Social security benefits, the alimony payor may seek a downward modification of his or her alimony payments after the chancery court considers the totality of the parties’ circumstances, not merely the receipt of derivative Social Security benefits. Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628. We find that Harris requires the chancellor to examine the impact the reception of derivative Social Security benefits causes and not the reception alone. We find also that it is the unpredictable impact that stymies foreseeability at the time of the initial alimony award. Thus, we hold that the Court of Appeals interpreted Harris incorrectly. [My emphasis]

¶16. At the time of the Alfords’ divorce, the law regarding derivative Social Security benefits provided that the spouse paying alimony was entitled to an automatic credit toward his alimony obligation “because the amount was based on his income.” Harris, 241 So. 3d at 626 (citing Spalding, 691 So. 2d at 439). In 2018, this Court overruled Spalding “to the extent that it holds an alimony reduction to be automatic for Social Security benefits derived from the alimony-paying spouse’s income.” Id. at 624. The issue in Harris involved a modification of a property settlement agreement, and this Court held that

Social Security benefits derived from the other spouse’s income do not constitute a special circumstance triggering an automatic reduction in alimony. When a spouse receives Social Security benefits derived from the other spouse’s income, the trial court must weigh all the circumstances of both parties and find that an unforeseen material change in circumstances occurred to modify alimony. Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628.

¶17. Harris did not say that derivative Social Security benefits can never be a basis for modifying an alimony award, only that the reception of derivative Social Security benefits does not “trigger[] an automatic reduction in alimony.” Id. The Court in Harris said that when a person receives derivative Social Security benefits, there can be a later modification of alimony as long as the chancellor “weigh[s] all the circumstances of both parties and find[s] that an unforeseen material change in circumstances occurred to modify alimony.” Id. If we were to agree with the Court of Appeals that “derivative Social Security benefits will not justify a subsequent modification of alimony if the benefits were anticipated or foreseeable at the time of the divorce[,]” Alford, 2019 WL 3297142, at *6 (citing Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628-29), one would not be able to seek a modification under Harris because it is foreseeable that most Americans will receive Social Security benefits at some point in their lives.

¶18. The Court of Appeals found that it was “clearly foreseeable” that Linda Alford would receive derivative Social Security benefits “in the near future” and it was the reception of those benefits that would not justify a later modification according to Harris. Alford, 2019 WL 3297142, at *6. While it may be foreseeable that a litigant will receive Social Security benefits, the impact of the benefits on both parties cannot be anticipated or foreseen. The chancellor must consider such benefits in conjunction with “all the circumstances of both parties” in order to determine whether there is an “unforeseen material change in circumstances” that justifies modifying alimony. Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628. It also may be said that it is clearly foreseeable that a person will get older and/or a person’s health will decline; yet courts have determined that these foreseeable events sometimes can create unanticipated, unforeseeable material changes in circumstances that justify the modification of alimony. See Broome v. Broome, 75 So. 3d 1132, 1141 (Miss. Ct. App. 2011) (“The chancellor found T.C.’s standard of living dramatically decreased over the years since the divorce decree due to his poor health and advanced age.”); Makamson v. Makamson, 928 So. 2d 218, 221 (Miss. Ct. App. 2006) (“These are specific findings that the increased costs, length of time before treatment was to begin and the stroke were not anticipated in the property settlement agreement.”). Contra Weeks v. Weeks, 29 So. 3d 80, 90-91 (Miss. Ct. App. 2009) (“With the extensive testimony concerning Deborah’s medical problems and the state of her health before the judgment after remand was entered, we cannot say that the increased expenses due to the progression of these problems was in any way unforeseeable by the parties.”).

¶19. In Harris, this Court considered the South Carolina case Serowski v. Serowski in deciding whether a modification of alimony “due to the start of Social Security benefits” was automatic or “require[d] a showing of a material or substantial change in circumstances[.]” Harris, 241 So. 3d at 628 (citing Serowski v. Serowski, 672 S.E. 2d 589, 593 (S.C. Ct. App. 2009)). In Serowski, the court did not find that the spouse’s reception of Social Security benefits was a foreseeability that would not allow a modification of alimony. Serowski, 672 S.E. 2d at 593 (“[T]he court found Wife’s increase in income due to her receipt of social security and annuity benefits had improved her ability to meet her needs.”). Instead, the court upheld a modification of alimony by considering the impact the Social Security benefits had on the wife’s income in conjunction with the increase in the wife’s net worth and the husband’s decline in health. Id. at 593-94 (“[T]he court properly considered both parties’ economic circumstances in reaching its finding.” (citing Eubank v. Eubank, 555 S.E. 2d 413, 417 (S.C. Ct. App. 2001))).

¶20. Similarly, this Court determines that Harris does not hold that the mere reception of derivative Social Security benefits is a foreseeable circumstance that would preclude a subsequent modification of alimony. Harris, 241 So. 2d at 628. In Harris we reversed and remanded, not because it was foreseeable that a person would receive derivative Social Security benefits, but because the trial court had failed to perform the proper analysis and determine whether all of the circumstances, including the impact the reception of derivative Social Security benefits had on both parties, constituted an unforeseen material change in circumstances. Id. at 628-29. Merely receiving derivative Social Security benefits alone is not enough to allow a modification of alimony because there must be judicial consideration of its impact on the parties, a factor that is not foreseeable at the time of the divorce. See Ivison v. Ivison, 762 So. 2d 329, 334 (Miss. 2000) (“An award of alimony can only be modified where it is shown that there has been a material change in the circumstances of one or both of the parties.” (citing Varner v. Varner, 666 So. 2d 493, 497 (Miss. 1995))); Tingle v. Tingle, 573 So. 2d 1389, 1391 (Miss. 1990) (“This change, moreover, must also be one that could not have been anticipated by the parties at the time of the original decree.” (citing Morris v. Morris, 541 So. 2d 1040, 1043 (Miss. 1989); Trunzler v. Trunzler, 431 So. 2d 1115, 1116 (Miss. 1983))).

¶21. We clarify our holding in Harris: when an alimony payor seeks an alimony modification based on the payee’s receipt of derivative Social Security benefits, the trial court must consider whether the impact of the derivative Social Security benefits on the parties constitutes a “material or substantial change in the circumstances[,]” Tingle, 573 So. 2d at 1391 (citing Clark v. Myrick, 523 So. 2d 79, 82 (Miss. 1988); Shaeffer v. Shaeffer, 370 So. 2d 240, 242 (Miss. 1979)), that arose after the original judgment and “could not have been anticipated by the parties at the time of the original decree[,]” Morris, 541 So. 2d at 1043; Trunzler, 431 So. 2d at 1116, and whether the change in circumstances calls for an alteration of alimony under the factors governing alimony awards from Armstrong, 618 So. 2d at 1280. See Steiner v. Steiner, 788 So. 2d 771, 776 (Miss. 2001) (“The chancellor must consider what has become known as the Armstrong factors in initially determining whether to award alimony, the amount of the award, and in deciding whether to modify periodic alimony, comparing the relative positions of the parties at the time of the request for modification in relation to their positions at the time of the divorce decree.” (citing Tilley v. Tilley, 610 So. 2d 348, 353-54 (Miss. 1992))).

That foreseeability aspect has puzzled me through the years. Your unclaimed SS benefits stop accruing when you reach 70, so 99.9% of people claim their benefits before then. You can’t get much more foreseeable than that. I think the bold language in Alford, above, clarifies that it is not the claiming of benefits that is unforeseeable; rather it is the economic impact that is unforeseeable and opens the gate to modification.

I don’t generally post about a case that is subject to a motion for rehearing, but with this blog winding down and this case being important to practitioners, I decided to go ahead with it. Besides, it’s a unanimous decision, and in my opinion it’s unlikely (and unforeseeable) that rehearing would be granted.