When Can a Chancellor Award Joint Physical Custody Without a Specific Request?

May 8, 2025 § 1 Comment

By: Chancellor Troy Odom, 20th Chancery District, State of Mississippi

Mississippi chancellors are often faced with custody determinations in which neither party has requested joint physical custody. This raises a critical question for chancery practitioners: may a chancellor award joint physical custody if it was not specifically requested in the pleadings?

The Short Answer

Yes. A chancellor retains the discretion to award joint physical custody if such an arrangement serves the best interest of the child — even if neither party expressly requested it.

Common Procedural Scenarios

Consider the following situations:

- A wife files for divorce, requesting sole custody. The husband either fails to answer or also requests sole custody. Neither pleads joint custody.

- A husband initiates a divorce action seeking sole custody. The wife answers in kind. Both consent to divorce on irreconcilable differences but leave custody to the court.

- In a paternity case, the mother seeks sole custody. The father either does not respond or likewise seeks sole custody. Joint custody is never pled.

In these examples, joint custody is not mentioned in any pleading. Still, a chancellor may determine – after applying the Albright factors – that joint custody is in the child’s best interest.

Statutory Framework

Mississippi Code Ann. § 93-5-24 governs custody determinations:

- Subsection (2) provides that joint custody may be awarded in irreconcilable differences divorces, “upon application of both parents.”

- Subsection (3) states that joint custody may be awarded in all other custody cases “upon application of on or both parents.”

While this language suggests join custody must be affirmatively requested, later case law has clarified the scope of judicial discretion in this area.

The Morris-Crider Shift

In Morris v. Morris, 758 So. 2d 1020 (Miss. Ct. App. 1999), the Court of Appeals interpreted the § 93-5-24 narrowly. There, both parties sought sole custody and failed to plead joint custody. The chancellor awarded joint custody, but the appellate court reversed, holding that the statute required at least one party to request joint custody before it could be awarded.

Judge Joe Lee dissented, arguing that by submitting the matter to the chancellor, the parties had effectively invited the court to determine the form of custody in the child’s best interest.

The Mississippi Supreme Court later adopted Judge Lee’s view in Crider v. Crider, 904 So. 2d 142 (Miss. 2005). In Crider, both parties filed fault-based divorce actions and each requested sole custody. They consented to an irreconcilable differences divorce and asked the court to decide custody. The chancellor awarded joint custody. The Supreme Court (Justice Cobb writing), upheld that decision and overruled Morris, holding:

A chancellor is never obliged to ignore a child’s best interest . . .; in fact, a chancellor is bound to consider the child’s best interest above all else.

Crider, 904 So. 2d at 144 (quoting Riley v. Doerner, 677 So. 2d 740, 744 (Miss. 1996))

The Crider Court interpreted “application of both parties” broadly, concluding that when parties submit custody to the court – even if phrased as a dispute over “primary custody” – they authorize the chancellor to make a full best-interest analysis, including awarding joint custody. (Crider, 904 So. 2d at 147).

Extension to Paternity and Third-Party Cases

The Mississippi courts have since extended the Crider analysis beyond traditional divorce actions.

In Brown v. Anslum, 270 So. 3d 69 (Miss. Ct. App. 2018), both parents sought sole custody in a paternity action. The chancellor awarded joint custody joint custody after a trial. Citing Crider, the Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that the parties’ request for sole custody constituted an application for custody sufficient to allow the court to award joint custody.

The Mississippi Supreme Court reinforced this principle in Darby v. Combs, 229 So. 3d 108 (Miss. 2017), a third-party custody dispute between maternal and paternal grandparents. The Court held that § 93-5-24 and the reasoning of Crider applied equally in such cases, affirming the chancellor’s authority to award joint custody even among thid parties. (Darby, 229 So. 3d at 114)

Practical Takeaways for Practitioners

Chancellors possess broad discretion to craft custody arrangements that serve the child’s best interests. The act of submitting a custody issue to the court – whether in divorce, paternity, or third-party case – constitutes an “application” sufficient to allow the court to award joint custody.

Pleadings requesting sole custody do not tie the chancellor’s hands. Rather, the paramount consideration remains the best interest of the child, as established through the Albright factors.

The “attestation” requirement for a will: Estate of Roberts v. Johnson

January 9, 2025 § 1 Comment

By: Donald E. Campbell

Michael E. Roberts died on December 19, 2016. Believing that he died intestate, Teresa Herd – the mother of Michael’s child – sought to open an estate appointing herself as administrator. Thereafter, Bryan Williams (Michael’s nephew), intervened claiming that a 2001 will (which named Bryan as a beneficiary and executor) was Michael’s true will. Michael’s brother and sister (Keith and Gloria) brought forward a 2016 will which they claim revoked the 2001 will and was Michael’s true last will and testament.

The 2001 Will left the following bequests: (1) His brother (Lindsey) the option to purchase his interest in Robert and Sons Mortuary; (2) Bryan Williams (nephew) $3,000 in cash and some personal property; (3) Jason Williams $1,500; (4) 1/2 of residue to any children born in the future; and (5) remainder of residue to Mississippi Delta Community College.

The 2016 will left the following bequests: (1) Jeremy Isiah Holmes $500 (and any unidentified/unborn children $10.00 each); and (2) all interest in Mortuary to brother Keith Roberts; 3) residiary to be equally divided between his 4 siblings (Lindsey, Gloria, Debra, and Keith).

The 2016 will was witnessed by Mary Blueitt and Lena Berry. Blueitt was deceased by the time of the hearing on the will, but Lena Berry was alive and able to testify (she was eighty-nine years old at the time of the hearing). Berry remembered Michael as “both a brother and a son” and they both attended the same church. She testified that one day Michael flagged her down at a service station and asked her to “do him a little favor.” Berry went to a funeral home owned by Michael that afternoon. Ms. Blueitt was already at the funeral home. Michael asked both ladies to sign a document — he never told them specifically that they were signing his will. However, Berry said that she noticed that the document said a “little something about a will” and that she saw the word “will” on it.

The chancellor heard testimony from a witness qualified as an expert in forensic document examination. According to the expert, the signature on the 2016 Will was not consistent with Michael’s signature on other documents and therefore the will was invalid as a forgery.

After hearing the competing testimony of Berry and the expert, Chancellor Kiley Kirk (Carroll County Chancery Court), issued what the Court of Appeals described as “a thorough and eloquent written judgment”, holding that the 2016 will was valid (the Judgment is here). (Estate of Roberts v. Johnson, 2024 WL 4889910 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024))

Teressa and Bryan appealed arguing that the chancellor erred in holding that the 2016 will was valid because Michael’s signature on the will was forged and the court did not give enough weight to the forensic expert’s testimony.

The Court of Appeals, in a unanimous opinion written by Judge Carlton affirmed the Chancellor Kirk.

The ultimate question was whether there was sufficient evidence that the will was “attested” by Berry. Miss. Code Ann. § 91-7-7 provides that the execution of the will “must be proved by at least one (1) of the subscribing witnesses, if alive and competent to testify.” The witnesses did not sign self-proving affidavits, therefore, Ms. Berry’s testimony was necessary to establish valid execution of the will.

To “attest” a will the witness must be able to testify that they know that the document they are signing is a will. To this end the testator must “publish” the will to the attesting witnesses, which means “a communication by the testator, or attributable to the testator that the subject writing is a will.”

Here, there were two arguments made that the will was not sufficiently attested: (1) there was no evidence that Michael ever told Ms. Berry that what she was signing was his will; and (2) the testimony of the expert witness that the 2016 will was not signed by Michael was sufficiently strong to overcome what testimony that Ms. Berry did supply.

Although the court of appeals acknowledged that there was no testimony that Michael ever told Ms. Berry she was signing a will, the court held that “publication may be accomplished through construction.” The court relied on a 1927 case from the Mississippi Supreme Court which recognized the following:

It is sufficient that enough is said and done in the presence and with the knowledge of the testator to make the witnesses understand that he desires them to know that the paper is his will, and that they are to be witnesses thereto. Green v. Pearson, 110 So. 862, 864 (Miss. 1927)

Therefore, with the deference given to the chancellor, the following facts were sufficient to establish attestation: that she knew Michael and witnessed him sign the document, and that she “saw it said ‘will’ over there.” As for the testimony of the forensic expert, the court held that it was up to the chancellor to weigh the credibility of the testimony and the chancellor did not err in giving more weight to Ms. Berry who was on the scene and could testify as to what happened.

One last, although important point. The appellants argued that the 2016 will should not have been admitted into evidence because it was not properly authenticated under Rule of Evidence 901 (“to satisfy the requirement of authenticating or identifying an item of evidence, the proponent must produce evidence sufficient to support a finding that the time is what the proponent claims it is.” Specifically, Ms. Berry could testify that it was her signature on the document but testified “I don’t know” when asked if the document she signed was Michael’s will. The court of appeals affirmed the chancellor’s holding that Miss. Code Ann. §§ 91-5-1 and 91-7-7 set out the standards for authentication of a will — and not Rule 901.

Professor’s Thoughts

This case is a reminder of the value of a self-proving affidavit when executing a will. Miss. Code Ann. § 91-7-7 provides that due execution of a will can be established by:

(1) bringing at least one of the witnesses to court to testify as to the valid execution. The problem with this approach, as demonstrated in this case, is that the witness may not remember what occurred when the execution was years ago. In addition, it may be, like in Herd, that witness may not have been told exactly what they were signing. In Herd, if Ms. Berry had not testified that she saw the word “Will” on the document, it is very unlikely that the will could have been proven.

(2) If none of the witnesses can be produced, the handwriting of the testator and the subscribing witnesses can prove the will. This, of course, requires testimony of individual(s) who can verify the signature of everyone involved in the execution. To see the potential problem with this, consider Matter of Beard v. Christmas, 334 So. 3d 1154 (Miss. 2022). In that case, the proponent of the will put on testimony of someone who could verify the signature of the testator and only one of the attesting witnesses — therefore execution of the will was not established.

(3) Execution of the will can be established by notarized affidavits of the subscribing witnesses. The affidavits can be attached to the will or made part of the will. The affidavits can also be signed at the time the will is executed. The affidavit must include the address of each witness. This approach — using a self-proving affidavit – alleviates the problems that can arise when trying to prove a will after the decedent dies and the witness is either dead or cannot remember what is required to prove due execution.

It is important to remember that an affidavit is testimony in affidavit form. That means that the testimony can be challenged/discredited if the statements made in the affidavit are not true (just like with live testimony). To this end, it is important that the witnesses signing the affidavit know what it says and agree to what they are “testifying” to.

Below is a sample of a self-proving affidavit

Affidavit of Subscribing Witness

STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

COUNTY OF ________________

Personally appeared before me, the undersigned authority in and for the jurisdiction aforesaid, ________________, whose address is _________________________, and __________________, whose address is _____________________________, who, being first duly sworn, state under oath the following:

That on the ___ day of ______________, 20__, the Testator, who is personally known to each of us, in our presence signed, published and declared the foregoing instrument of writing to be his/her Last Will and Testament; that we at his/her request and in his/her presence and in the presence of each other signed our names thereto as witnesses to its execution and publication; that at the time of execution of the instrument the testator was over the age of 18 and was of sound and disposing mind and memory.

Dated this ___ day of ___________, 20____.

____________________________________

Witness

____________________________________

Witness

SWORN TO AND SUBSCRIBED before me this the [] day of [], 20.

_____________________________________

NOTARY PUBLIC

My Commission Expires:

_____________________

<From Robert A. Weems, Wills and Administration of Estates in Mississippi (3d.)>

Happy New Year! And a Question

January 2, 2025 § 3 Comments

By: Donald Campbell

Happy New Year to all! I’m getting back into the groove here at the law school and an interesting topic has been circulating on a Property Professor list serve I follow: should the Rule Against Perpetuities still be taught in the first year Property law course? This same topic circulated on the list serve about 5 years ago and the consensus was that it should be taught. This time, however, the consensus has flipped, with most saying that they do not teach it or that they just introduce it but do not test it. There are 4 primary justifications given for moving away from the Rule: (1) the Rule has lost relevance with the move to abolish the Rule or to adopt the modern “wait-and-see” approach; (2) the time it takes to teach the rule is disproportionate to likelihood that it will arise in practice; and (3) the Rule is best left to upper level classes (such as Wills and Trusts); and (4) the Bar exam rarely tests the Rule (and the NextGen bar will not test it at all).

I have always taught and tested on the Rule. I have also taught (and tested) the other common law rules that abolish future interests: Doctrine of Worthier Title, the Rule in Shelley’s Case, and Destructibility of Contingent Remainders.

I come to the hive-mind to ask: should I still teach the Rule? What about the other rules that destroy future interests? I teach Wills and Trusts and I do not teach the Rule, so if the students do not get exposure to it in Property they are not likely to have any exposure to it. Does the Rule still have relevance today? Does it come up often in practice? Any other thoughts?

The key to “McKee”: Analyzing The Reasonableness of Attorney’s Fees

November 20, 2024 § 3 Comments

By: Donald E. Campbell

In two recent cases the Mississippi Court of Appeals has addressed the award of attorney’s fees in estate matters. In the first case, Estate of Watson v. Watson, 2024 WL 4354006 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024) the court reversed the chancellor based on the award of attorney’s fees over other creditor claims in an insolvent estate. While distribution of assets in an insolvent estates is a topic for another post, in opinion the court notes that the chancellor held that the fees were “reasonable and appropriate” without doing an appropriate analysis under McKee v. McKee, 418 So. 2d 764 (Miss. 1982). McKee sets out seven factors that a court should consider when evaluating attorneys fees. These factors, have become known as the “McKee factors”.

Similarly, in Estate of Stimley v. Merchant, 2024 WL 4439985 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024), an attorney representing an estate sought approval of attorney’s fees in the amount of $48,167.75. After a hearing, the chancellor said the fees were an “astronomical sum”, and would issue an opinion as to what would be a “reasonable fee in light of … services rendered.” Ultimately the court issued an order which provided the following — with no further explanation:

The law firm appealed the judgment which was assigned to the court of appeals. Writing for a unanimous court (Judge Carlton not participating), Judge Lawrence held that the chancellor erred in failing to apply the McKee factors in determining the appropriate amount of fees.

Right to attorney’s fees

The following statute provides for “reasonable” fees to be paid to an attorney providing services to an estate.

Miss. Code Ann. § 91-7-281. Attorney’s Fees

In annual and final settlements, the executor, administrator, or guardian shall be entitled to credit for such reasonable sums as he may have paid for the services of an attorney in the management or in behalf of the estate, if the court be of the opinion that the services were proper and rendered in good faith. Where the executor, administrator, or guardian acts also as attorney, the court may allow such executor, administrator, or guardian credit for his reasonable compensation as attorney in lieu of his compensation as executor, administrator, or guardian.

The attorney is entitled to “reasonable” fees if the services “were proper and rendered in good faith.” The determination of reasonableness is left to the discretion of the chancellor and an appellate court will review “the reasonableness of the [attorney’s fees] award only for an abuse of discretion, and we will not reverse unless the award is manifestly erroneous or amounts to a clear or unmistakable abuse of discretion.” (¶7). The court ultimately determined that the failure to do any analysis of the McKee factors warranted reversal.

Professor’s Thoughts

I thought it might be worthwhile to examine what is required for an adequate analysis of the McKee factors. As a starting point, chancellors are given a lot of discretion in awarding fees (reviewed for an abuse of discretion). Furthermore, the Stimley court notes “‘the lack of a factor-by-factor analysis does not immediately warrant a reversal.” However, there must be proof ‘support[ing] an accurate assessment of fees under the McKee criteria” (¶ 8) and “the mention of the McKee analysis is not enough to support a chancellor’s award of attorney’s fees.” (¶10).

So the question is: what does a sufficient McKee analysis look like? In footnote 9 of the Stimley opinion, the court references Mauck v. Columbus Hotel, 741 So. 2d 259 (Miss. 1999) as a case where the court did an adequate analysis. Therefore, in the discussion below, the judgment entered by the Chancellor in Mauk will be considered.

McKee Factors: Where did they come from?

McKee was a divorce case in which the chancellor awarded attorney’s fees to the wife’s attorneys and the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the amount of fees awarded was excessive. In granting guidance to courts in determining the appropriate amount of fees the Court held:

In determining an appropriate amount of attorneys fees, a sum sufficient to secure one competent attorney is the criterion by which we are directed. Rees v. Rees, 194 So. 750 (Miss. 1940). The fee depends on consideration of, in addition to the relative financial ability of the parties, the skill and standing of the attorney employed, the nature of the case and novelty and difficulty of the questions at issue, as well as the degree of responsibility involved in the management of the cause, the time and labor required, the usual and customary charge in the community, and the preclusion of other employment by the attorney due to the acceptance of the case.

We think it is not the best practice to estimate the time expended as the basis for a fee as the approximation is more susceptible to error, and thus more suspect than properly maintained time records. Estimates, however, can properly be considered by the court but the attorney who does so should have a clear explanation of the method used in approximating the hours consumed on a case. We are also of the opinion the allowance of attorneys fees should be only in such amount as will compensate for the services rendered. It must be fair and just to all concerned after it has been determined that the legal work being compensated was reasonably required and necessary.

Most of these factors were first set out by the Fifth Circuit in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Exp., Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) and then cited with approval by the United States Supreme Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983). There are 2 factors adopted by the Court in McKee that are not in the cases or the ethics rule: (1) relative financial ability of the parties, and (2) responsibility required in managing the case. I pulled the briefs from McKee to see if the parties cited to authority for these elements — but they did not. So these two factors are unique to Mississippi’s evaluation of attorney’s fees and, at least with regard to the ability to pay factor, may not be appropriate in every case.

The test for attorney’s fee is really a modified-McKee approach

If you look at cases after McKee what you see is that courts will cite to the factors set out in Rule 1.5 (which does not include the two referenced above) and call these the “McKee factors.” For example, in Mississippi Power and Light v. Cook, 832 So. 2d 474 (Miss. 2002), the Supreme Court set out the Rule 1.5 factors, cited McKee, and then said: “These factors are sometimes referred to as the McKee factors.” Id. at 486. Therefore, the standard for determining a reasonable attorney’s fee is best viewed as requiring an analysis relevant Rule 1.5 factors and the additional McKee factors if relevant.

None of the following factors are determinative, but should considered as a whole in evaluating a particular fee.

(1) Relative financial ability of the parties

This is the most unusual of the factors set out in McKee to evaluate the reasonableness of an attorney’s fee. This factor is not found in Rule 1.5 or in any other state lists of reasonableness factors. The question of whether a fee is reasonable not the same question as whether the fee is collectible. It may be that a client will never be able to pay a fee — but that does not make the fee unreasonable.

I think that this factor was listed because it is relevant in domestic relations cases. For example, in Dauenhauer v. Dauenhauer, 271 So. 3d 589 (Miss. Ct. App. 2018), the wife in a divorce action stipulated that the amount of attorney’s fees sought by her husband was reasonable, but argued that it was not appropriate to award fees because of her inability to pay. The court of appeals agreed and held that the award of fees was not appropriate.

Therefore, this factor will be relevant in domestic cases, but is not relevant in other situations where the ability to pay is not a relevant consideration.

(2) The skill and standing of the attorney employed [Rule 1.5(a)(7)]

An attorney that specializes in a particular area of law or who is well respected in a particular area of law may be in high demand and therefore able to charge a higher fee than someone without such reputation or skill. The Mauck court titles this factor as “The Skill Requisite to Perform the Legal Services Properly”:

(3) Novelty and difficulty of issues in the case [Rule 1.5(a)(1)]

If an attorney takes on a case of unusual difficulty or that raises a novel claim, fees that might otherwise be excessive can be considered reasonable: “Cases of first impression generally require more time and effort on the attorney’s part. Although this greater expenditure of time in research and preparation is an investment by counsel in obtaining knowledge which can be used in similar later cases, he should not be penalized for undertaking a case which may ‘make new law.’ Instead, he should be appropriately compensated for accepting the challenge.” Johnson, 488 F.2d 714 at 718.

(4) The responsibility required in managing the case

This is another factor that is unique to McKee and is not found in Rule 1.5 (or in the Johnson factors). In fact, in my research I cannot find any other jurisdiction that has this factor. I am not sure what the Supreme Court relied upon in adopting this factor. It is not referenced in the parties’ briefs in McKee. However, in the McKee briefs there is a great deal of discussion of the numerous lawyers that were involved and the time that they spent on the case. This element may be better framed as a factor that is in Rule 1.5(a)(4): The amount involved and the results obtained.

Assuming this factor is meant to cover the amount involved and the results obtained, the question is whether the fee is in line with the nature of the representation. For example, in Matter of Fordham, 668 N.E.2d 816 (Mass. 1996), a lawyer charged approximately $50,000 (227 hours) in representing a defendant in a DUI case. The testimony received indicated that the lawyer obtained a very good outcome for the defendant (the case was dismissed based on a novel argument), but even the lawyer’s expert testified that she had never heard of a fee in excess of $10,000 in a DUI case. Therefore, even if the lawyer was entitled to a “bonus” for obtaining favorable results, the $50,000 charge was clearly excessive. On the other side, if the matter involved a great deal of money and the lawyer is able to obtain favorable results, a larger fee may be warranted.

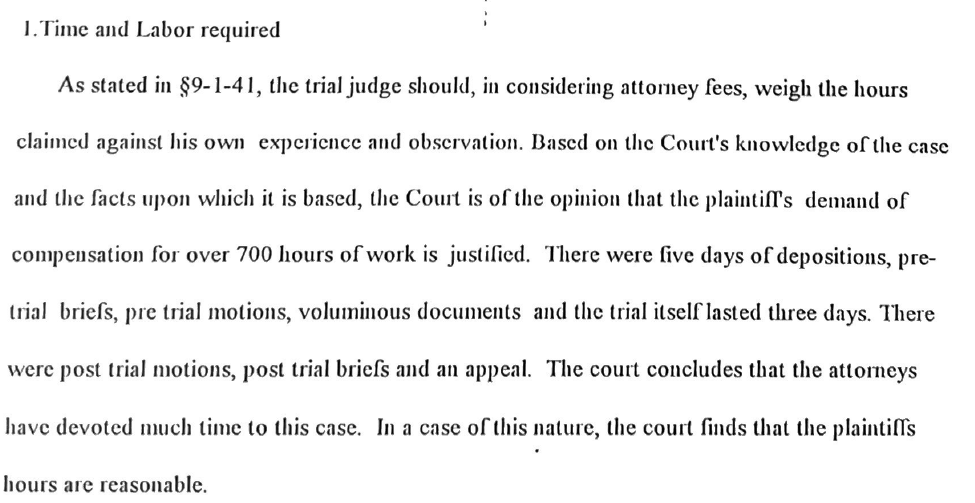

(5) Time and labor required [Rule 1.5(a)(1)]

A case that requires a lot of time and effort to resolve would justify a larger fee amount than one where very little effort is required the matter. In this regard, judges should bring into consideration their own background and experience: “The trial judge should weigh the hours claimed against his own knowledge, experience, and expertise of the time required to complete similar activities. If more than one attorney is involved, the possibility of duplication of effort along with the proper utilization of time should be scrutinized. The time of two or three lawyers in a courtroom or conference when one would do, may obviously be discounted. It is appropriate to distinguish between legal work, in the strict sense, and investigation, clerical work, compilation of facts and statistics and other work which can often be accomplished by non-lawyers but which a lawyer may do because he has no other help available. Such non-legal work may command a lesser rate. Its dollar value is not enhanced just because a lawyer does it.” Johnson, 488 F.2d at 717.

The discussion below from Mauck involved cancellation of a lease.

Notice the court references Miss. Code § 9-1-41, which provides that a judge can rely on their “experience and observation” in evaluating whether the time spent on the case was reasonable:

Miss. Code Ann. § Evidence of attorney fees’ reasonableness

In any action in which a court is authorized to award reasonable attorneys’ fees, the court shall not require the party seeking such fees to put on proof as to the reasonableness of the amount sought, but shall make the award based on the information already before it and the court’s own opinion based on experience and observation; provided however, a party may, in its discretion, place before the court other evidence as to the reasonableness of the amount of the award, and the court may consider such evidence in making the award.

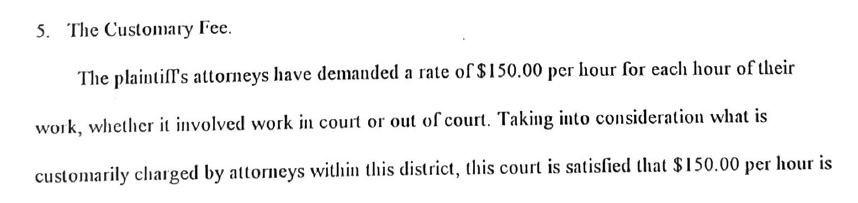

(6) The usual and customary fee charged in the community [Rule 1.5(a)(3)]

The baseline to determine whether a fee is reasonable or excessive is what a competent lawyer would charge for the service in the community. This is the loadstar approach — “the most useful starting point for determining the amount of a reasonable fee is the number of hours reasonably expended on the litigation, multiplied by a reasonable hourly rate.” BellSouth Communications v. Bd. of Supervisors, 912 So. 2d 436, 446-47 (Miss. 2005).

The factors discussed above may justify a higher fee than would normally be charged, but for a run-of-the-mill case, the fee should be in line with what would ordinarily be charged for the type of case by lawyers in the community.

(7) Whether the attorney was precluded from undertaking other employment by accepting the case [Rule 1.5(a)(2)]

An attorney who agrees to accept a case and spend time on it to the exclusion of other cases would be entitled to charge a larger fee than an attorney who just accepted a case as part of the ordinary book of business. This is particularly relevant where the lawyer has other available business which they must turn down because representation of the client would result in a conflict of interest. This factor would also cover situations where a lawyer is brought in at the last minute to handle a matter and has to make the client’s case a priority – delaying the lawyer’s other work. This is more than just the lawyer’s business decision to accept a case and refuse another. This is meant to cover a situation where a lawyer could have other business, the client is aware that the lawyer, in taking the client’s case, will be precluded from accepting the other matter (that is why the Rule requires that the situation be “apparent to the client”).

The Mauk court judgment:

Factors were not discussed in McKee, but are included Rule 1.5:

(8) Time limitations imposed by the client or the circumstances [Rule 1.5(a)(5)]

This is meant to cover a situation where a client needs work performed in an expedited manner or where the client comes to the lawyer at the last minute for legal assistance. In these situations, a lawyer would be entitled to charge more for a fee. Essentially the client is paying a premium for the lawyer to drop everything they are doing to handle the client’s matter.

(9) The nature and length of professional relationship with the client [Rule 1.5(a)(6)]

This factor is meant to address situations where a lawyer and client have a long-standing relationship. A long-standing client who has accepted increased fees over time and who has presumably been pleased with the lawyer’s representation should not be able to, in hindsight, argue that the fee is unreasonable (essentially arguing that another lawyer would have charged them less). This factor recognizes good will that develops over time between a lawyer and client has value.

(10) Whether the fee is fixed or contingent [Rule 1.5(a)(8)]

Questions of reasonableness will almost always arise in the context of an hourly rate fee. Contingent fees are not governed by the same standards of reasonableness. There are a couple of reasons that cases that are taken on a contingency fee basis would justify a higher fee than one taken on an hourly rate. The first reason is based in public policy – contingency cases allow those who could not otherwise afford a lawyer to have their case heard. Second, the lawyer who accepts a contingency fee case is taking the risk that they will not recover anything. Acceptance of this risk justifies the recovery of a higher amount of fees. Of course, if the lawyer takes a case where there is no uncertainty in the plaintiff’s right to recovery. For example, in Attorney Grievance Comm’n v. Kemp, 496 A.2d 672 (Md. Ct. App. 1985), the court held that recovery under a contingency fee was unreasonable where there was a statutory right to recover certain insurance proceeds. The court noted: “[w]hen there is virtually no risk and no uncertainty, contingent fees represent an improper measure of professional compensation.” Id. at 676.

A contingency fee can also be unreasonable if the percentage charged is unusually high.

When can a person be presumed dead? An analysis of Miss. Code Ann § 13-1-23 and the 2024 Amendment

October 30, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

There is a longstanding common law rule that a person who has been absent for an extended period of time can be presumed to be dead. See Thayer, A Preliminary Treatise on Evidence at the Common Law pp. 319-324 (1898). Mississippi has codified this common law rule since at least 1856, and the statute remained largely unchanged until 2024. This post will cover first the long-standing part of the statute and then the 2024 Amendment.

7 Years Absent or Concealed Can be Presumed Dead

Mississippi Code Ann. Section 13-1-23(1) provides:

(1) Except as otherwise provided in subsection (2) of this section, a person who shall remain beyond the sea, or absent himself or herself from this state, or conceal himself or herself in this state, for seven (7) years successively without being heard of, shall be presumed to be dead in any case where the person’s death shall come in question, unless proof be made that the person was alive within that time. Any property or estate recovered in any such case shall be restored to the person evicted or deprived thereof, if, in a subsequent action, it shall be proved that the person so presumed to be dead is living.

Here are some cases where the statute was applied and interpreted:

- In Learned v. Corley, 43 Miss. 687 (Miss. 1870), Henry Augustus sailed from New York in 1856 en route to Spain. After five days at sea there was a storm and neither the ship nor any of its passengers were heard from again. Ten years later, in 1866, a hearing was held, and he was presumed to be dead under the statute.

- In Manley v. Patterson, 19 So. 236 (Miss. 1896), the Mississippi Supreme Court interpreted the phrase “absenting” in the statute. In that case, a husband, wife, and two children disappeared after the husband became “involved in some trouble” in Hazlehurst. The children were left property interest in the will of their grandmother. A guardian was appointed to protect the children’s interest. The contingent beneficiaries of the property under the will sought a declaration that the children were presumed dead. The Supreme Court refused to allow the party to rely on the presumption of death statute, because the statute requires proof that the person “absent” or “conceal” themselves, which requires the ability to do so by a person’s own volition. The presumption of death cannot apply to children who, “by reason of their tender age, [are incapable] of ‘absenting’ themselves from the state, or of ‘concealing’ themselves within it.” The court noted that evidence could still be put on to establish that the children were actually dead, but the party could not utilize the presumption of death.

- In Frank v. Frank, 10 So. 2d 839 (Miss. 1942), Isom Frank had a life insurance policy payable to his wife, with the contingent beneficiary being his next of kin. Frank’s purported wife was Ollie Lee. The problem was that Ollie Lee married Dan Evans in 1912. Shortly after the marriage Dan moved to Arkansas. None of Dan’s Mississippi relatives knew where he was. In 1927, Ollie wrote to Dan’s sister in Arkansas asking about his whereabouts. The sister responded that Dan had drowned. Thereafter, in 1935, assuming Dan was dead, Ollie Lee married Isom Frank. However, at some point Dan reappeared. The Court (over two strong dissents), held that the statutory presumption of death was rebutted by the fact that Dan reappeared. Therefore, Ollie’s second marriage to Isom Franks was invalid, and she was not entitled to the insurance proceeds as the wife of Isom Franks.

- In Martin v. Phillips, 514 So. 2d 338 (Miss. 1987), John Martin and his wife, Grace Martin owned 340 acres in Grenada County as joint tenants. Thereafter, on January 20, 1969, John parked his car near the Grenada spillway and disappeared. In 1976 (7 years after his disappearance), Grace filed an action in the Grenada County Chancery Court to have John declared dead under the statute. The Chancery court held that there was sufficient evidence to raise a presumption that John was dead. Thereafter, in 1977, Grace sold the property she held as joint tenants with John to the Phillip’s for $95,000. In a twist that would make soap operas jealous, John reappeared in August 1983 (the court notes that there was no explanation for this “spectral reemergence from the dead”). John filed a petition in chancery court to have the order declaring him dead set aside, and to have the property he owned restored to him. John based his claim on the statute, which provides that, if the person who is declared dead is later determined to be living, “[a]ny property or estate recovered in any such case shall be restored to the person evicted or deprived thereof….” The chancellor set aside the declaration of death but refused to void the conveyance of the property. The Supreme Court reversed the chancellor, holding that it was error to grant a 12(b)(6) dismissal without developing the facts to show the purchasers of the property from Grace did not actually know that John was still alive and that they relied on that fact in purchasing the property. Essentially they would have to show that they were good faith purchasers.

- The most recent case citing the statute is Matter of Johnson, 312 So. 3d 709 (Miss. 2021). In that case, Ashley filed a petition in the Hinds County Chancery Court asking the chancellor to declare her father, Audray Johnson, dead, arguing that he “had been gone from his physical body for more than seven years and should be presumed dead.” Audray (who had changed his name to Akecheta Andre Morningstar), testified at a hearing on the petition that Audray’s “spirit expired more than seven years ago, and Morningstar now occupies Audray’s physical body.” The supreme court quoted the chancellor with approval in affirming the denial of the declaration of death:

The reality is that we are identified by our physical body. Our physical body is given a birth certificate and social security number to identify our person and ultimately a death certificate. Our physical body can be identified by our DNA, fingerprints, and physical appearance. It is uncontested that the physical body of Audray Johnson is the body Morningstar now occupies.

Id. at 711.

2024 Amendment: Zeb Hughes Law

On December 3, 2020, Zeb Hughes (21) and Gunner Palmer (16) went missing while hunting ducks on the Mississippi River near Vicksburg. While search teams found their boat and some hunting equipment, the bodies of the boys have never been recovered. Now, more than three years after the disappearance, under the statute discussed above, the families would still have to wait four more years before a death certificate could be issued. The mother of Zeb Hughes, who worked to have the law amended noted that there are a number of times she has needed a death certificate to handle affairs on behalf of her son and could not do so because seven years have not passed.

The 2024 Amendment, which is titled the “Zeb Hughes Law” provides that a person who has undergone a “catastrophic event that exposed the person to imminent peril or danger reasonably expected to result in loss of life” and whose absence cannot be explained after a diligent search is presumed to be dead if there is uncontradicted testimony from those having “firsthand knowledge of the event” (law enforcement officers, first responders, search and rescue personnel, eye witnesses, etc.) that the person died in the “catastrophic event.” The hearing can be held 2 years after the event and the “loss of life shall be proven by clear and convincing evidence.” Notice of the hearing must be provided to the “coroner, the district attorney and the sheriff of the county” in which the event occurred.” If the evidence is sufficient to establish the presumption of death, the death is presumed to have occurred at the time of the catastrophic event.

The law also amended Miss. Code Ann. § 41-57-8, and requires the State Registrar of Vital Statistics to issue a death certificate upon receipt of a court order finding a presumption of death.

Professor’s Thoughts

I first heard about this amendment at a CLE for public defenders. The speaker before me was talking about the impact of this amendment in the criminal prosecution/defense world in cases where someone is missing and foul play is suspected. Looking at the statute, I think it is going to raise some interesting issues in the future, for example:

- What is meant by “catastrophic event”? There is no definition of the term. Does the phrase mean situations where a person has gone missing — like Zeb Hughes? Is the catastrophic event the presumed drowning? Is it the event that caused them to drown — Zeb’s mother thinks it was the turbulent waters of the Mississippi River although that is speculation. The speaker at the CLE said that he believed that the phrase “catastrophic event” was intended to be more like a hurricane or flood. That definition of catastrophic event would not cover the missing person situation without some kind of natural disaster or other widespread event. This interpretation is justifiable if based on the text but not if you look at legislative intent (and the title of the amendment).

- There is also a question of what to include on the death certificate. A medical examiner may be unwilling to sign off on a death certificate that states a presumed cause of death without having a body to confirm the cause of death.

- There is also no provision for what happens if the person presumed to be dead ultimately reappears. The amendment to the statute specifically states that section (1) which provides that if a person presumed dead appears they are entitled to have their property restored.

The need to clarify the “reasonable necessary” standard with regard to easements by necessity

October 18, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

Word v. U.S. Bank, 2024 WL 4489615 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024), is a case decided by the Mississippi Court of Appeals about an easement by necessity. While the court ultimately reached the correct decision based on Mississippi law, the opinion included some analysis that needs to be clarified/corrected in future cases for the benefit of practitioners and judges.

Facts of Word v. U.S. Bank

There are two parcels at issue in the case — from a common owner named Zeno Griffin. The parcel ultimately owned by William Word was conveyed by Griffin in 1996. Word purchased the lot in 2019. Thereafter, Griffin conveyed a second parcel in 1997 — this is the parcel that U.S. Bank ultimately obtained via foreclosure in 2019. This second parcel was landlocked when it was conveyed in 1997. Until 2019, access to the landlocked parcel was over a road on the Words’ property.

In early 2019 (prior to the bank’s foreclosure), Word blocked the road because he suspected the owners of the parcel were trafficking drugs. After Word blocked access, the owners began to use a route across another parcel of land (land retained by Zeno Griffin).

When the bank took ownership of the property, it filed suit in Perry County Chancery Court alleging that an easement by necessity was established over Word’s property and it had the right to continue to use the right-of-way that Word had blocked.

The case was assigned to Chancellor Michael C. Smith. Judge Smith ultimately held that the Bank had satisfied its burden to establish an easement by necessity and ordered Word to allow the Bank to cross his property. Word appealed.

The Appeal

The case was assigned to the Court of Appeals, and in an opinion by Judge Smith for a unanimous court (with Judge Wilson joining only part of the opinion and Judge Weddle not participating), the court reversed and rendered.

The Court of Appeal’s rationale was based on the following: (1) the Bank’s parcel was landlocked when it was severed from the commonly owned property, but at that time the Word property had already been severed (no longer owned by the common grantor Zeno Griffin); therefore, it was not possible to impose an easement by necessity over property that the common grantor did not own at the time of the severance creating the landlocked parcel; and (2) the bank “failed to provide any evidence at trial about the specific costs associated with using the available alternate route to access its parcel of land”. Specifically, the Court held: “even if U.S. Bank possessed a possible right to an easement by necessity over Word’s parcel, as in Hobby, it would still have constituted an abuse of discretion to grant the easement ‘without evidence of the alleged higher costs’ associated with utilizing the alternative available route.”

Professor Thoughts: Correct result but confused analysis of the “necessary” element of easement by necessity

I agree with the first part of the court of appeal’s opinion, but the second part is inconsistent with precedent and the purpose of implied easements, and provides confusing guidance about what is required to establish an easement by necessity.

Beginning with the part of the opinion that I agree with: At the time that the bank parcel was severed and landlocked, the Word parcel had already been sold. Therefore, to the extent there was an easement by necessity – it was over the property retained by the common grantor – not over the property that was not owned by the grantor at the time of the severance.

The part I disagree with: the court’s statement that the chancellor erred in failing to accept evidence of the cost to establish the easement (presumably over the property retained by Griffin). The rationale for requiring evidence of costs in the context of an easement by necessity is to establish whether there is necessity for an easement across the property retained by the grantor. The only reason cost is relevant is when the claimant has potential access to a public road but they argue requiring them to use that access is too expensive — and therefore an easement across their grantor’s property is necessary.

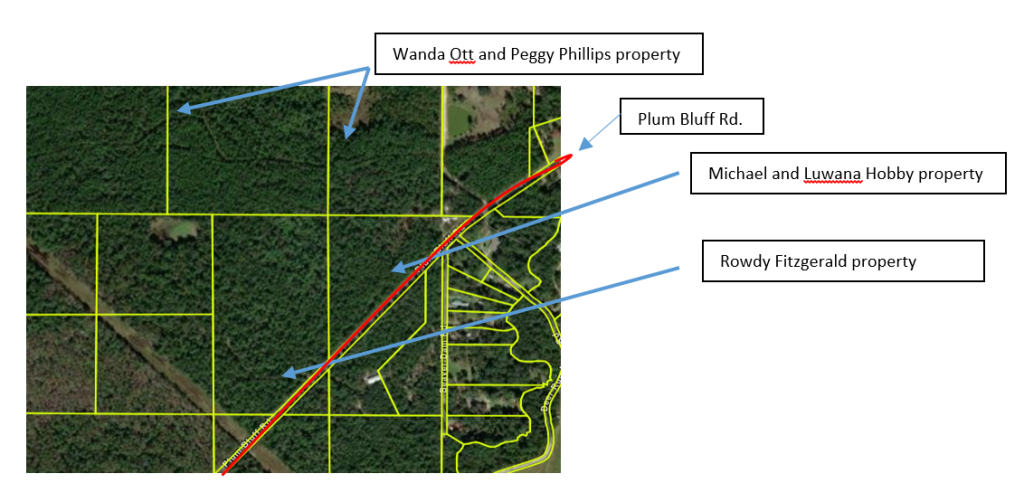

The problem begins with Hobby v. Ott

This confusion about how costs play into an easement by necessity analysis began with Hobby v. Ott, 382 So. 3d 1156 (Miss. Ct. App. 2023). In that case, E.B. Taylor owned property in George County. The property abutted a public road (Plum Bluff Road). In 1969, Taylor conveyed property that abutted Plum Bluff Road to J.R. Hobby and Betty Hobby (this property ultimately was held by Michael and Luwana Hobby). After this conveyance, Taylor retained a parcel that abutted Plum Bluff Road – and also owned the property behind the Hobbys. That meant that at the time of the conveyance, Taylor’s property still had access to a public road. Thereafter, in 1970, Taylor made three conveyances of property behind the Hobby’s, but retained the property abutting Plum Bluff Road. That meant that, at the time of the 1970 conveyances, Taylor created 3 landlocked parcels. Over time, these landlocked parcels came into the ownership of Wanda Ott and Peggy Phillips. At some point after 1970, Taylor conveyed the property he retained (and which abutted Plum Bluff Road) to Rowdy Fitzgerald. Here is screenshot of the tax parcels as of October 17, 2024 just to give a sense of how things stood at the time of the lawsuit:

According to the complaint filed by Ott and Phillips, there is a logging road across the Hobby’s property that they used to access Plum Bluff Road. At some point the Hobbys refused to allow Ott and Phillips to use the road, so Ott and Phillips sued for an easement by necessity across the Hobby’s land.

The Hobbys argued that the there were other properties which Ott and Phillips could seek to cross, so an easement across their property should be denied. One particular alternative route was over the land now owned by Rowdy Fitzgerald (the land that was retained by the original grantor Taylor after he conveyed the Hobby property). There was a 100 foot right of way given to Mississippi Electric Power Association across the property in 1972. After considering the alternatives proposed (across the Hobby land or across the Fitzgerald land), the chancellor concluded, “an easement across the Hobby’s triangular parcel of property is the most convenient and least onerous means to access the Ott and Phillips’ properties, and other alternatives would involve a disproportionate expense or inconvenience.” Therefore, the chancellor granted an easement by necessity across the Hobby’s property. The Court of Appeals reversed and rendered the chancellor’s order – holding as follows:

“Because the record reveals the existence of alternative routes, Ott and Phillips were required to provide evidence regarding the costs of accessing their properties by the alternative routes to prove that they were entitled to an easement by necessity across the Hobby properties. A thorough review of the record shows that Ott and Phillips did not provide any specific evidence of the expense involved in obtaining access by alternative routes… We find that the chancery court abused its discretion by granting Ott and Phillips an easement by necessity over the Hobby properties without evidence of the allegedly higher costs of the alternative routes.” (1163)

This evidentiary requirement – imposing on a party the obligation to show the cost of various alternative locations/properties to impose an easement — is not consistent with prior caselaw addressing the elements of an easement by necessity.

Remember, an interest in land such as an easement is subject to the statute of frauds and must be in writing to be enforceable. However, in limited circumstances a court will imply an easement as a matter of law even though there is no writing. Why? With regard to an easement by necessity the belief is that the grantor would have not have intentionally landlocked a piece of land, therefore, a court (enforcing what is the presumed intent of the parties), will impose an easement across property retained by the grantor for the benefit of the landlocked parcel.

With that justification in mind, consider the elements that a claimant must show to establish an easement by necessity: (1) easement is necessary; (2) the dominant (landlocked) and servient (parcel that easement will be placed on) estates were once part of a commonly owned parcel; (3) the implicit right-of-way arose at the time of severance from the common owner. (Hardy v. Hardy, 241 So. 3d 636, 638 (Miss. Ct. App. 2018)).

Where does the requirement that the claimant establish the cost of various means of access fit in? The Court of Appeals considers it to be under the “necessary” element: “Here, ‘[o]ur concern is only whether alternative routes exist. If none exist then the easement will be considered necessary.” (¶ 14) But cases discussing necessity do not ask a party to compare the costs to impose an easement over the property of various neighbors to determine whether an easement exists. Instead, necessity and the cost of access concerns the cost of the landowner to access a public road from their own property.

Thus in Burns v. Haynes, 913 So. 2d 424 (Miss. Ct. App. 2005), a party sought an easement by necessity across a neighbor’s property even though they could build a driveway across their own property to get to the public road. The court first (correctly) recognized that Mississippi only requires “reasonable necessity” for an easement by necessity and not “strict necessity”. [NOTE: Strict necessity was historically required for an easement by necessity – which required the claimant to have no possibility of access such that, if a party could access a public road by building a bridge they could not satisfy the necessity element.]

To determine whether there is “reasonable necessity” the court “looks to whether an alternative would involve disproportionate expense and inconvenience.” (430-31). In Burns, the claimant did not put on put on any evidence that building a new drive way would be prohibitively expensive – therefore, because the party could not establish the “necessary” element – the claim was denied. Similarly, in Hardy v. Hardy, the claimant sought an easement by necessity across his grantor’s property. The court denied the easement because there was a driveway that provided access to a public road. The claimant argued that the public access point was “one-half mile farther north and only provided access to his property and not to his home place…” and that the route was not passable because it was overgrown. The court held that the test is not whether it would be more convenient to have a different location of access, there must be a showing of necessity to justify the grant of an implied easement across the grantor’s land.

Classic cases where there is reasonable “necessity” involve where the claimant would have to build a bridge on their property to reach a public road. Mississippi Power v. Fairchild, 791 So. 2d 262 (Miss. Ct. App. 2001); Rotenberry v. Renfro, 214 So. 2d 275, 278 (Miss. 1968)).

These cases put the burden on the party claiming an easement by necessity to show that the alternative route across their own property is cost prohibitive so they are entitled to an easement across their grantor’s property.

In Hobby v. Orr, the court of appeals (I think because of the nature of the arguments presented by the parties), misapplied how the element of “necessity” . The question is not the expense to impose an easement across one neighbor’s property as opposed to other routes. The question is whether, assuming the landowner has access to a public road, can they demonstrate that it would be so expensive to use that access that it would be unreasonable to use that route to gain access to a public road.

So, how should Hobby v. Orr have been decided? Although the facts are somewhat convoluted, it seems clear that at the time that Taylor conveyed Hobby his parcel first (in 1969), Taylor retained property with access to Plum Bluff Road and it was not until later (1970) when he conveyed property to the predecessors of Ott and Phillips that those parcels were landlocked. Therefore, if an easement by necessity is available (which there is a strong argument that there is), then it should be imposed across the land that was retained by the grantor at the time the lots were landlocked (property now owned by Rowdy Fitzgerald) and not over the Hobby’s land (regardless of whether it would be more convenient or cost effective to cross the Hobby’s land).

The unfortunate legacy of Hobby v. Orr

Now, getting back to Word v. U.S. Bank. In my opinion, the second section of the opinion titled: “U.S. Bank presented no evidence regarding the costs of using an available alternative route to access its property” simply should have been omitted. It was unnecessary to the holding and furthers the incorrect analysis in Hobby v. Orr. There was no evidence that U.S. Bank had access to a public road across its own property, therefore, there was no need to consider the cost of access.

The court does note that there is a statutory mechanism for obtaining an easement for a landlocked parcel which could be obtained over property of someone other than the grantor. Miss. Code Ann. 65-7-201 provides that when someone wants a private road over the land of another they shall utilize an eminent domain proceeding. Under this statute, if a right-of-way is granted, the servient property owner is entitled to compensation for the property interest that was lost. This is a very important point — when an easement is implied by necessity, the servient property owner is not entitled to compensation because the easement is imposed based on the presumed intent of the parties at the time of the conveyance. That is why it critically important that easements by necessity only be granted across the land of the grantor that created the landlocked parcel.

Final thoughts: Hopefully in a future case the appellate courts will clarify the “reasonable necessity” element (and hopefully move away from the Hobby analysis).

Reimbursement Alimony: What it is and when to seek it

October 15, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Professor Deborah H. Bell

Three types of alimony (periodic, lump sum, and rehabilitative) are well-established in Mississippi. A fourth type – reimbursement alimony – was recently recognized by the court of appeals for the first time since its adoption by the supreme court in 1999. The decision opens the door for broader application of reimbursement alimony.

The Mississippi Supreme Court, in Guy v. Guy, 736 So. 2d 1042 (Miss. 1999), held that one who supports their spouse through school may be entitled to “reimbursement alimony” if their spouse seeks divorce shortly after graduating and before the plaintiff receives the anticipated financial benefit of the training. In Guy, a husband spent $35,000 to put his wife through nursing school during their three-year marriage. She filed for divorce one month after graduation. The supreme court agreed with other state courts that “the contributing spouse should be entitled to some form of compensation for the financial efforts and support provided to the student spouse in the expectation that the marital unit would prosper in the future as a direct result of the couple’s previous sacrifices.” Id. at 1044. The supreme court held that the husband was entitled to lump sum reimbursement alimony based on his actual contributions to his wife’s degree.

There were no reported cases addressing reimbursement alimony for the next twenty-four years. In 2023, the court of appeals addressed the issue in Whittington v. Whittington, 373 So. 3d 1060 (Miss. Ct. App. 2023) in an opinion written by Judge Wilson and joined by Judges Barnes, Carlton, Greenlee, and Emfinger. Judge McDonald dissented without a separate opinion. A dissent authored by Judge McCarty was joined by Judges McDonald, Lawrence, and Smith. Judge Westbook joined in part. The dissent found the facts in Whittington significantly different from those in Guy.

The court of appeals affirmed a chancellor’s order that a wife of ten years repay her husband for $125,879 in separate property funds that he used to pay off her student loans. Two years after the couple married, the wife decided to pursue a two-year master’s degree in nursing. Her post-degree earnings were three times that of her husband’s. The couple subsequently agreed to pay off her student loans with an annuity he received because of an injury. Four years later, she sought a divorce and custody of their two children. The chancellor divided their marital assets of $248,000 equally and ordered the wife to repay her husband for the funds used to pay her student loans. She appealed.

The court of appeals affirmed, citing Guy. The court rejected the wife’s argument that Guy was factually distinguishable on two counts:

First, in Guy, the wife filed for divorce less than a month after obtaining her degree, whereas Lacey filed for divorce about six-and-a-half years after she obtained her degree and about four-and-a-half years after Ben paid off her student loans. . . . Second, Lacey points out that the Guys were only married for about three years and had no children, whereas Lacey and Ben were married for about ten years and have two children.

Id at 164.

The majority noted that the husband most surely expected that the marriage would endure for longer and that the financial benefits would continue for more than four years. “[I]t was not Ben’s “expectation” that Lacey would file for divorce only four years after he had paid off her student loans totaling $125,879.89.” Id. at 1065.

Professor’s notes:

Based on the facts in Guy, reimbursement alimony appeared to be a limited doctrine. Whittington opens the door for reimbursement alimony claims in cases in which the decision to divorce comes years after the plaintiff’s support. Attorneys should add this to the list of possible claims for financial recovery. Reimbursement alimony extends beyond support for tuition and books – the court in Guy stated that a supporting spouse may be reimbursed for direct expenditures toward education such as tuition and books as well as the costs of housing, food, clothing, and other living expenses.

In Guy and Whittington, the courts characterized reimbursement alimony as lump sum alimony. Presumably, reimbursement alimony has the characteristics of lump sum alimony – it should vest at the time of the order, be nonmodifiable, and should not terminate upon the death of either party or the recipient’s remarriage.

It is worth noting that the court was evenly split in Whittington.

Jones v. Curtis: Serve a Rule 81 Summons on your Counter-Petition or Else

October 11, 2024 § 1 Comment

By: Chancellor Troy Odom (Rankin County Chancery Court)

“The party who brings suit confers by that act all necessary personal jurisdiction as to himself.” Miss. Chancery Practice § 2.13 at 37 (2017 ed.). That’s axiomatic, right? In a circuit or federal court practice, a defendant who files a counterclaim does not serve a Rule 4 summons on the plaintiff—the plaintiff already subjected themselves to the personal jurisdiction of the court through their initial filing.

That rule does not apply to chancery court litigation initiated through a Rule 81 summons. For example: You are a respondent in a custody modification proceeding brought by your ex-spouse. You file a counter-petition for a downward modification of child support. For personal jurisdiction to attach, you must serve your ex with a copy of the counter-petition and a Rule 81 summons. Rely to your own peril on simply filing the answer and counter-petition on MEC or emailing a copy of the counter-petition to counsel opposite.

The issue of whether a respondent must serve the petitioner with process to obtain personal jurisdiction arose in Pearson v. Browning, 106 So. 3d 845 (Miss. Ct. App. 2012). The parties to this proceeding were previously divorced. Browning, the wife, had been awarded custody of the subject child through the divorce judgment. Years later, Pearson, the non-custodial parent, filed a petition to modify custody and for other relief. Browning filed a counter-petition, seeking to have Pearson held in contempt for non-payment of a retirement benefit ordered through the divorce judgment. Browning never served Pearson with a Rule 81 summons on her counter-petition.

When Pearson’s initial petition was dismissed, there remained for adjudication only Browning’s counter-petition for contempt. The trial for Browning’s counter-petition was set for November 3, 2010, by court administrator’s notice. On the day of trial, Pearson, unrepresented by legal counsel, “inartfully” argued lack of adequate notice and requested a continuance, which was denied. The court proceeded to trial and eventually found Pearson in contempt and ordered him to pay Browning $53,528.22. Pearson appealed, arguing lack of personal jurisdiction since Browning failed to serve him with a Rule 81 summons on the counter-petition.

As an aside, the court of appeals made observations at the beginning of its analysis that serve as important reminders to chancery court practitioners: “In a matter that requires a Rule 81 summons and does not use a Rule 81 summons, the resulting judgment is void because it is made without jurisdiction over the parties.” Pearson, 106 So. 3d at 848. The court also stated that “for no additional Rule 81 summons to be required, the order that continues the trial date must be signed on or before the original trial date.” Id. (emphasis added).

Ultimately, the court held that the trial court lost jurisdiction over Pearson because he was not served with a Rule 81 summons on the counter-petition. Interestingly, the court of appeals stated that before Pearson’s initial claims were dismissed, he “simply was not entitled to a Rule 81 summons because he was the plaintiff.” Id. at 848. “Because Pearson was the plaintiff prior [to his claims being dismissed] he cannot properly raise a jurisdictional issue before that date.” Id. at 848. By being the plaintiff, Pearson consented to personal jurisdiction. Id. These statements by the appellate court would indicate that a counter-petition of the type enumerated in Rule 81(d)(1) or (2) does not require a Rule 81 summons so long as the initial claim remains.

[Judge’s note: This case seemed to hang on the fact that the initial petition was dismissed prior to trying the issues raised in the counter-petition. The cases discussed below do not make this distinction.]

Three years later, the court of appeals in Curry v. Frazier, 119 So. 3d 362 (Miss. Ct. App. 2013) tweaked its tune. The parties to this case were subject to a judgment of paternity, child support, and visitation. Eleven years after entry of that order, the non-custodial father, Curry, filed a petition asking solely for the child’s name change. The custodial mother, Frazier, counter-petitioned for an upward modification of child support. No Rule 81 summons was ever issued on the counter-petition. After the trial court entered a judgment modifying child support, Curry appealed.

The court of appeals stated, simply:

A Rule 81 summons needed to be issued for the modification issue. No Rule 81 summons was ever issued for the modification of child support issue. Without the issuance of a proper Rule 81 summons, the court had no jurisdiction to hear the case.

Curry, 119 So. 3d at 365.

Thus, a Rule 81 summons was necessary for the counter-petition. It is not clear whether the initial petition to change name was pending at the time of trial.

[Judge’s note: Pearson is not mentioned in Curry. However, the two cases are arguably consistent. Presumably, Curry’s petition to change the name was fully decided at an earlier hearing, which would have the same effect as the dismissal of Pearson’s initial claims.]

Similarly, in Estate of Labasse, 242 So. 3d 167 (Miss. Ct. App. 2017), one of the contestants to the decedent’s last will and testament filed a petition for contempt against the executrix of the estate. A Rule 81 summons was issued for the executrix and mailed to the attorney for the estate. The court of appeals held that the petition for contempt, filed within an ongoing estate proceeding, was subject to the service requirements of Rule 81. No personal service meant no personal jurisdiction.

[Judge’s note: It is becoming clear that the Court of Appeals considers any Rule 81 claim raised in ongoing litigation a distinct proceeding, necessitating separate service of process.]

In Hilton v. Harvey, 284 So. 3d 850 (Miss. Ct. App. 2019), the court of appeals held that the 120-day time limitation on service of process under Rule 4(h) does not apply to matters falling under a Rule 81 summons. In doing so, the appellate court assumed the necessity of a Rule 81 summons for a counter-petition. No analysis was afforded the issue of whether a summons was necessary in the first place.

Now, with the recent case of Jones v. Curtis, No. 2023-CA-987-COA (Miss. Ct. App. September 17, 2024), there should be no question that service of a Rule 81 summons is necessary for a counter-petition—regardless of whether the initial petitioner’s claims survive.

Jones, the mother of the child, filed a petition to modify the joint physical custody arrangement. Curtis, the child’s father, filed an answer and counter-petition, also requesting modification of custody. Following trial, the court awarded physical custody to the father.

Jones appealed, arguing the chancellor lacked jurisdiction to hear either party’s petition due to insufficient service of process. (¶14). The appellate court’s analysis follows:

¶ 20 . . . While Rule 81(d)(4) states that an answer is not required in a modification-of-custody action, Curtis’s filing also set forth his counter-complaint for modification, which does require a Rule 81 summons. M.R.C.P. 81(d)(5); see Hilton v. Harvey, 284 So. 3d 850, 854-55 (¶¶15-16) (Miss. Ct. App. 2019); Pearson, 106 So. 3d at 849 (¶19). It is undisputed that Curtis failed to provide Jones with Rule 81 process. This Court has held that “in Rule 81 matters, a Rule 81 summons must be issued; otherwise, service is defective.” Pearson, 106 So. 3d at 850 (¶27). When service is defective, “[any] resulting judgment is void because it is made without jurisdiction over the parties.” Id. at 848 (¶9).

* * *

¶22. . . . Curtis failed to provide Jones with Rule 81 service upon the filing of his counter-complaint for modification. Vincent, 872 So. 2d at 678 (¶8); Pearson, 106 So. 3d at 850 (¶27). As a result, “[t]he only avenue where the chancery court still would have jurisdiction over [Jones at the time of the hearing] is if [she] waived the lack of a Rule 81 summons by appearing.” Pearson, 106 So. 3d 851 (¶28).

(emphasis added).

Judge’s Analysis

The norm for most chancery court practitioners, at least in Rankin County, is to avoid raising personal jurisdictional issues unless necessary to secure a continuance or stave off a surprise counter-petition. There is honor in proceeding to trial as previously agreed without the expense or hassle of service of process. As a result, attorneys skip jurisdictional squabbles by simply trying the case. This makes life easier—and justice speedier—for all concerned.

But it is difficult at times to describe to an attorney (when the issue is raised) why they must serve a Rule 81 summons on their counter-petition. Why? they ask: hasn’t personal jurisdiction already attached—the petitioner has already subjected themselves to the personal jurisdiction of the court through their respective filing.

I guess the best way to describe it is that any cause of action listed in Rule 81(d)(1) or (2) cannot be a “counterclaim.” Instead, those causes of action are their own separate and distinct “petitions,” no matter how related they are to the claims made in the initiating pleading. Because those causes of action are special, a Rule 81 summons must be issued served. It does not matter that there is ongoing litigation.

However, does that mean that Rule 13(a)—compulsory counterclaims—and its language on res judicata and collateral estoppel does not apply? Or, does Rule 13(a) still apply, but Rule 5 does not.

On January 10, 2020, the Supreme Court Advisory Committee on Rules filed a Motion to Amend Rule 81 (Motion No. 2020-91), proposing many changes. One of those proposed changes would allow for Rule 5 service on counter-petitions. The motion mentions Pearson and Hilton as the motivating factor for the proposed change.

The Mississippi Supreme Court sought comment on the motion. I cannot find where any comments were received by the Court. I believe the motion is still pending.

Enforcing an oral contract to transfer land – Equitable estoppel

October 8, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

William Howard, Jr. and John Carpenter Nelson, Jr. own property in Forrest County, Mississippi just north of Camp Shelby. The area is wooded and undeveloped. There is a “woods road” that runs from a paved road (Northgate Road) that traverses the land owned by Howard and Nelson, but the location of the road requires Howard and Nelson to cross the other’s property.

In May/June 2021, Howard and Nelson orally entered into an agreement whereby Nelson would convey about .06 acres to Howard, which would allow Howard to use the existing road without crossing Nelson’s property. In exchange, Howard agreed to convey to Nelson a 15-foot strip of property to provide full access off of Northgate Road to Nelson’s property and also a right of ingress/egress to existing woods road. The agreement was never reduced to writing.

In reliance on the agreement, Howard paid to have a survey completed, had deeds drafted, and obtained a partial release from a bank in anticipation of the transaction being completed.

May 5, 2022, before executing the deeds, Nelson passed away and his estate refused to recognize the agreements.

Howard filed a complaint in Forrest County Chancery Court alleging breach of the oral contract for the exchange of land. Although recognizing that the statute of frauds ordinarily required a contract for the transfer of property to be in writing, Howard alleged an exception to the statute of frauds applied – equitable estoppel. The case was assigned to Chancellor Rhea Hudson Sheldon. Chancellor Sheldon held that the agreement had to be in writing to be enforceable and that equitable estoppel did not apply and granted Nelson Estate’s motion to dismiss.

Howard appealed and the case was assigned to the Court of Appeals. A panel consisting of Judges Wilson, Westbrooks, and McDonald heard the case. Judge Wilson wrote for a unanimous court affirming the chancellor: Howard v. Nelson, 2024 WL 4354185 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024).

The Court of Appeals began its analysis by noting that, ordinarily, the transfer of an interest in land must satisfy the statute of frauds to be enforceable. However, there is a “well-established” exception to the statute of frauds – equitable estoppel. If a claim for equitable estoppel can be established, a party can enforce an agreement even though it does not satisfy the statute of frauds.

The elements to establish equitable estoppel are: (1) belief and reliance on some representation; (2) change of position as a result thereof; and (3) detriment or prejudice caused by the change of position. The court of appeals noted that equitable estoppel should only be allowed in exceptional circumstances.

Here, Howard did not allege any facts that would demonstrate the type of detriment that would justify the application of equitable estoppel – instead “he undertook some typical preparations for a land transaction” (hiring a lawyer, having surveys done, obtaining a partial release). Furthermore, a year passed between the time of the oral agreement and the death of Nelson, further indicating that Howard did not suffer the type of detrimental reliance contemplated by equitable estoppel.

The court affirmed the chancellor’s dismissal of Howard’s complaint.

Professor’s Notes

The equitable estoppel exception to the statute of frauds is premised on the idea that a party should not be able to make an oral agreement, know/expect that the other party would rely on that oral promise and then, after that reliance has occurred, seek to refuse enforcement of the agreement. Crucial to an equitable estoppel claim is sufficient evidence of reliance to an extent that it would be unjust to deny enforcement of the oral agreement.

To give an example of when equitable estoppel would apply, consider Martin v. Franklin, 245 So. 2d 602 (Miss. 1971). In this case (which was cited by the Court of Appeals), the state straightened a road that went across property owned by Martin and Franklin. The parties agreed to verbally swap land so that the road became the agreed-upon border of the property. Thereafter, Martin, relying on the oral agreement, constructed a house on the property. Franklin, who observed the construction, did not say anything until the contractor was putting locks on the doors and then asked the contractor, “Do you know you are building a house on my land?” The Supreme Court held Franklin could not enter into an oral agreement, stand by and allow Martin to incur the cost of a house in reliance on the oral promise and then seek to deny the existence of an agreement. Therefore, the oral promise to convey the property was enforceable.

The court of appeals is correct to note that the type of reliance and prejudice contemplated by equitable estoppel is more than “typical” costs that would be incurred in the purchase of property. If that was all that was required it would make the statute of frauds meaningless. The prejudice such that it would be inequitable to allow the other party (here Nelson) to deny enforcement of the agreement despite there being no writing. This might be building on the property or selling their home in reliance on the promise of the seller to convey the property (the Property textbook favorite Hickey v. Green, 442 N.E.2d 37 (Mass. Ct. App. 1982)).

Podcast recommendation — and request for suggestions

October 4, 2024 § 4 Comments

By: Donald Campbell

I am going to be traveling over the next couple of days. I really enjoy listening to podcasts while I am driving. So, I thought I would recommend a podcast that I came across on my last trip and ask for suggestions from you for good podcasts.

The podcast that I would like to recommend is Celebrity Estates Podcast. From King Charles to Larry King, the podcast takes one estate an episode and uses it to demonstrate a particular legal point and discuss whether the estate plan was effective (usually the answer is no.).

So now I ask you — what podcast would you recommend for a long trip?