Just when you thought the Mortmain law was dead (Mississippi Baptist Foundation v. Fitch)

October 1, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

This is an unusual post. It is about a 2023 case dealing with Mississippi’s Mortmain law – a law that was repealed in the early 1990’s.

Reverend Harvey McCool died on August 31, 1969, survived by his wife Maggie McCool. In his will, he devised a mineral interest that he owned to the Mississippi Baptist Foundation (MBF), to be held in trust for his wife and his sister for their lives. At the death of his wife and sister, the MBF was to use the property “for the use and benefit of Foreign Missions carried on by, under the auspices of, or participated in by, the Mississippi Baptist Convention.”

Maggie died on April 17, 1973, with a will leaving her property to 3 children from a previous marriage (including the mineral interest). Reverend McCool’s sister died on February 5, 1986.

In December 2019, MBF filed a complaint in Amite County Chancery Court to probate Reverend McCool’s will and confirm title to the mineral interest. Because MBF was challenging the constitutionality of Mississippi’s Mortmain statute, the Attorney General, in addition to the heirs and successors of Maggie, were made parties to the suit.

The case was assigned to Chancellor Debbra K. Halford. The chancellor held that the Mortmain laws were constitutional, and that MBF was divested of any interest in the property in 1979 – ten years after the death of McCool.

MBF appealed and the case (Mississippi Baptist Foundation v. Fitch, 359 So. 3d 171 (Miss. 2023)) was decided by the Mississippi Supreme Court on March 16, 2023. The case was heard by a panel of Justices King, Chambelin, and Ishee. Justice King wrote the opinion for a unanimous court affirming Chancellor Halford.

The outcome in this case turns on the validity of Mississippi’s Mortmain law. These laws, which trace their origins to the Magna Carta, were designed to restrict the ability of organizations (explicitly including charitable and religious organizations) to hold property. In Mississippi, Mortmain laws date back to 1857. The 1890 constitution prohibited all testamentary devises to religious or ecclesiastical institutions. By 1940, the Constitution had been amended to provide that no person could devise more than one-third of their estate to “any charitable, religious, educational or civil institutions to the exclusion” of certain heirs, and also included the following restrictions: (1) any devise, regardless of amount, was invalid if devised less than 90 days before the death of the testator; and (2) the organization could only hold the property for 10 years after the death of the testator, and if the organization had not sold the property within 10 years, it reverted back to the estate of the testator. The loosening of the prohibition from 1890 to 1940 was to bring some balance – by continuing to protect against the concerns that the Mortmain law was designed to address while at the same time providing some ability for the testator to promote religious or charitable organizations.In 1987/1988 the Constitution and statute were amended again to make it clear that the ten year restriction begins to run “after such devise becomes effective as a fee simple or possessory interest.”

Thereafter, in 1992/1993 the Mortmain law – both the Constitutional provision and the related statutes were repealed.

It was the 1940 version of the Mortmain law that was in effect at the time of Reverend McCool’s death. Under that law, MBF could only hold the property in fee simple absolute for 10 years before it reverted back to Reverend McCool’s estate. MBF argued that McCool’s will devised a life estate to Maggie and McCool’s sister, and that MBF did not acquire a fee simple absolute interest – triggering the 10 year limitation – until 1986 at the death of McCool’s sister. And, MBF argued, since the Mortmain laws were repealed in 1992/1993 – their limitations did not apply when the 10 year reversion kicked in in 1996. In addition, MBF argued, if the Mortmain statute did apply, it was unconstitutional.

In a Court of Appeals case from 2012 (Hemeter Properties, LLC v. Clark, 178 So. 3d 730 (Miss. Ct. App. 2012)), the court held that, where a legal life estate was left to family members, with a remainder interest to a charitable organization, the 10 year time frame did not start until the family members died because the organization could only sell the property with the right of possession after the family member’s death.

The Court noted that this case was not like Hemeter. Here, the MBF owned the property as a trustee with the right to dispose of the property at any time (unlike Hemeter). Therefore, because MBF had the right to dispose of the property at the death of Reverend McCool, the ten years to dispose of the property began running at Reverend McCool’s death in 1969. MBF did not sell the mineral interest before 1979, therefore the property interest reverted to estate of Reverend McCool in 1979.

The Court refused to address MBF’s argument that Mississippi’s Mortmain law is unconstitutional – holding that MBF knew (or should have known) about the Mortmain statute issue at Reverend McCool’s death and waited more than 40 years to challenge the statute’s constitutionality. Therefore, MBF was barred both legally (under the statute related to claiming an interest in land) and equitably (failure to act timely to protect their rights) from making a constitutional argument.

Professor Thoughts

One thing I always tell my students in Wills & Trusts and Property Law classes is how far reaching their representation can be. Mistakes in property transfers (either by deed or by will) may not be recognized until years later. This case is certainly an example of that. I only teach Mortmain statutes in passing, because they have been repealed or declared unconstitutional in almost all jurisdictions today.

Because a number of lawyers practicing today have probably never studied (or perhaps heard of) Mortmain laws, I thought a short discussion would be worthwhile. If nothing else, this should get you a point if this is the answer to a trivia question.

The Statutes of Mortmain were first enacted in the late 1200’s during the reign of Edward I. The goal was to prevent land from passing into the hands of the church and out of the taxing authority of the crown. This was the same justification for enactment of Mortmain laws in the United States – taking property permanently out of the stream of commerce and the taxing authority of the state.

This was not the only justification, however. There was also the concern that a testator who is near death could be in a position to be unduly influence by charitable organizations – leveraging the testator’s fear of death to secure a bequest. Hence, Mississippi’s 1940 version of the law which invalidated bequests made within 90 days of death.

A final justification (and this is my favorite) is to prevent a testator who was not charitable during life to be charitable at death at the expense of their family. Mississippi’s law reflected this by restricting the amount that could be devised to no more than one-third of the testator’s estate.

It might be worthwhile setting out the constitutional challenges to the Mortmain statute argued by MBF. While the Supreme Court did not address these arguments, other states have invalidated their Mortmain statutes based on constitutional challenge.

The essential argument is that Mortmain laws violate the Equal Protection Clause because they are not able to survive rational basis review. Specifically, MBF’s brief argues that the purpose of the Mortmain laws are to prohibit the testator from being unduly influenced by the named organizations and they are not rationally related to that goal because:

- They do not take into account the susceptibility of the individual testator to undue influence or whether the testator was actually in their last illness at the time the bequest was made;

- They do not take into account whether the testator has close family that need to be protected from overreach;

- They do not take into account the fact that others are in “an equal position to improperly influence the testator, including lawyers, doctors, nurses, clergymen, caretakers, housekeepers, companions, and the like” and there is no reason to believe that religious or charitable organizations are more “unscrupulous than greedy relatives, friends, or acquaintances”;

- The statutes do not address inter vivos gifts and non-charitable gifts that have the same potential for overreaching.

To the extent that a proper case comes forward, these arguments remain valid arguments against the Mortmain law. It should be noted, however, that there are counter arguments. For example, the fact that the charity could sell the property within 10 years and not lose the value of the bequest could save the statute if a valid challenge is ever raised.

Keeping the faith – state of mind in an adverse possession case

September 27, 2024 § 1 Comment

By: Donald Campbell

Signaigo v. Grinstead, 2024 WL 2284923 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024)

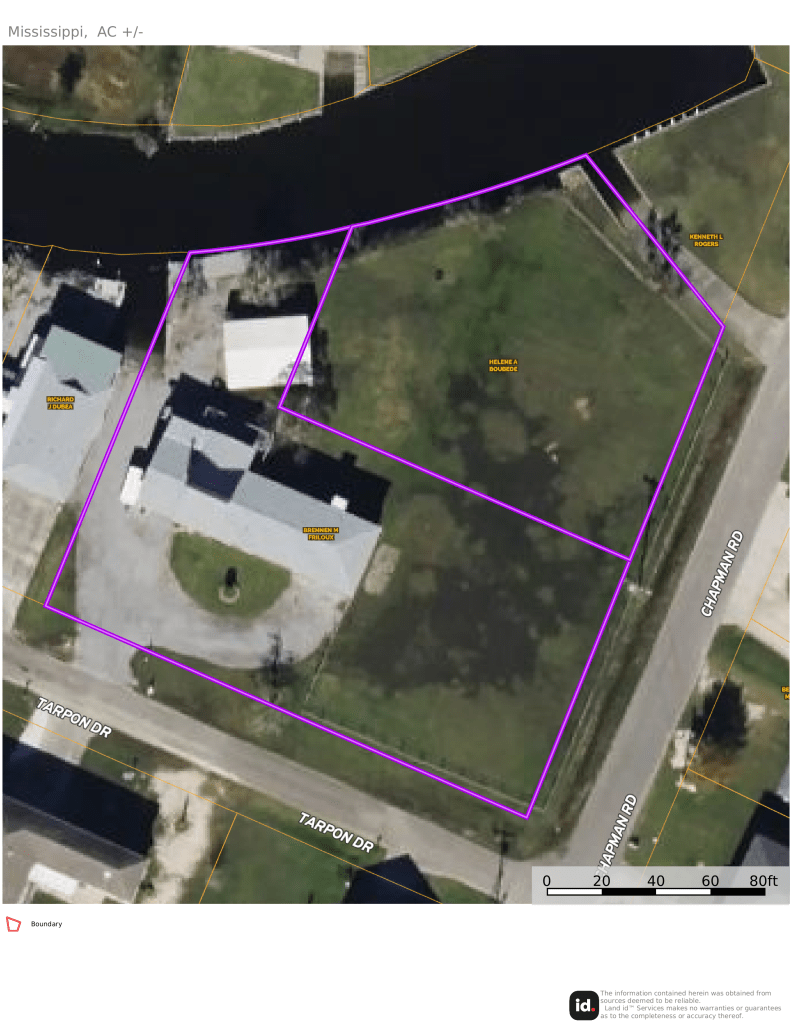

William and Judith Signaigo purchased property in Shorelines Estates in Hancock County in 1997. The adjacent property was owned by Helene A. Boubede at that time. Boubede lived in Iowa and, when she died, the property went to her daughter Myrna Grinstead.

After moving onto the property, the Signaigos fenced in part of their property and all of the Boubede property. When asked if she gave any thought as to whether they were fencing in someone else’s property, Mrs. Signaigo testified: “No. The only thing I was concerned about was the fact that there’s water here and there is a street there and the dogs were bringing stuff back from other places and we wanted to fence it in.” She also testified that she and her husband knew that the property was not theirs. In fact, they tried to contact Ms. Boubede about purchasing the property but were not able to get in contact with her. Beginning in 1997, the Signaigos performed all upkeep on the disputed property: mowing the grass, removing debris following hurricanes, removing trees, and providing fill material.

On September 15, 2021, the Signaigos filed a lawsuit against Boubede/Grinstead claiming ownership of the property by adverse possession. The case was assigned to Chancellor Margaret Alfonso. After a hearing, the chancellor found that adverse possession had not been established because the the Signaigos did not establish: (1) claim of ownership of the property; or (2) open and notorious possession. Signaigos appealed and the case was assigned to the Court of Appeals.

Judges Barnes, Greenlee, and McCarty were on the panel that heard the case. Judge Greenlee, writing for a unanimous court, affirmed Chancellor Alphonso.

To establish a claim of ownership by adverse possession in Mississippi the adverse possessor must satisfy the following six elements for 10 years (see Miss. Code Ann. 15-1-13): (1) under claim of ownership; (2) actual or hostile; (3) open, notorious, and visible; (4) continuous and uninterrupted for 10 years; (5) exclusive; and (6) peaceful.

The dispositive issue was whether there was a “claim of ownership.” There have been a split of decisions in Mississippi when it comes to what it means to claim ownership. Some older cases have said that the key to a claim of ownership is the taking of steps demonstrating that the adverse possessor is making a claim to the property. Therefore, the determining factor was what the adverse possessor did to possess the property — not the state of mind of the adverse possessor. For example, in 1846, the High Court of Errors and Appeals of Mississippi held: “There is no doubt, that the possession of a mere intruder, is protected to the extent of his actual occupation; whilst one who has color of title is protected to the extent of the limits of his title.” (Grafton v. Grafton, 16 Miss. 77, 91 (Miss. 1846)). Again, in Levy v. Campbell in 1946, the court notes that, as far back as 1858: “it has been settled rule in this state that although the possession may have been begun by a mere intruder without any color of title at all, the occupant may establish title by adverse possession to the extent of his actual occupation.” In short — it does not matter that the adverse possessor knows that they are trespassing so long as they actually take possession.

A 2004 Mississippi Supreme Court case (Blackburn v. Wong, 904 So. 2d 134 (Miss. 2004)) rejected the idea that possession is all that matters and required the adverse possessor to be acting in good faith. “Good faith” means that the adverse possessor must have a reasonable belief that they have rights in the property. In Blackburn a lawyer built a law office onto the property of another. Shortly after the building was constructed, a surveyor informed the lawyer that his office was across the property line. At that point the lawyer testified he had three options: (1) contact the true owner to try to purchase the property; (2) dig up the sewer lines and tear down the building; or (3) wait for the adverse possession time to pass and claim ownership. The lawyer chose to wait out the time for adverse possession. The lawyer possessed the property from 1971 through 1999 (when the suit commenced). The court, without much analysis held that, because the lawyer found out that he did not own the disputed strip shortly after the building was completed, he could not claim the property by adverse possession.

Relying on the Blackburn holding, the court in Signaigo held that, because the Signaigos knew that they did not own the property at the time they went into possession, they could not establish the element of “claim of ownership”. Therefore, the heirs of Boubede own the disputed parcels. The court remands the case for a determination of heirship.

Professor Thoughts

The justification of allowing adverse possession is to ensure that property is used and not abandoned by an absentee owner without any hope of putting the property back into use. To this end, there are three approaches that states have taken to determine whether an adverse possessor can demonstrate a “claim of title”: (a) good faith; (b) bad faith; and (c) objective approach (state of mind is irrelevant).

The majority of states take the approach that the state of mind is irrelevant. The rationale for taking this approach is two-fold: (1) if the justification of adverse possession is to reward the industrious possessor and punish the true owner who has not bothered to check on their property for more than 10 years — whether the adverse possessor knew the property was not theirs or whether they had a reasonable belief it was, is irrelevant; and (2) requiring testimony of a state of mind can encourage adverse possessors to lie on the stand to conform their testimony to what is required in the jurisdiction. Those older Mississippi cases followed this approach — emphasizing the possession over the state of mind. In adopting the objective approach (and abandoning the good faith approach), the Washington Supreme Court noted: “The doctrine of adverse possession was formulated at law for the purpose of, among others, assuring maximum utilization of land, encouraging the rejection of stale claims and, most importantly, quieting titles… Because the doctrine was formulated at law and not at equity, it was originally intended to protect both those who knowingly appropriated the land of others and those who honestly entered and held possession in full belief that the land was their own… Thus, when the original purpose of the adverse possession doctrine is considered, it becomes apparent that the claimant’s motive in possessing the land is irrelevant and no inquiry should be made into his guilt or innocence.” (Chaplin v. Sanders, 676 P.2d 431, 435 (Wash. 1984)(en banc))

Some states (after Wong, Mississippi is in this category) require that the adverse possessor act in good faith (have a reasonable belief that they own the property to satisfy the claim of ownership requirement). The justification for this approach (and this is apparent in both the Wong and Signaigo case) is the refusal to reward land pirates (ie intentional trespassers). Under this approach, it does not matter that the Signaigos put the property to use from 1997 until 2021 or that Blackburn had his law office on the property from 1971 until 1999 — the fact that they were using the property knowing it was not theirs, defeated their claim.

The final approach, bad faith, is only followed by one state that I am aware of — Arkansas (Fulkerson v. Van Buren, 961 S.W. 2d 780 (Ark. Ct. App. 1998)) Under this approach, to satisfy the “claim of ownership” element, the adverse possessor must be able to show that they knew that the property was not theirs and they intended to claim it as their own. The rationale is that someone should not be able to gain title (and the owner should not lose title) by accident. To claim title by adverse possession, the possessor must intend to do so.

The bottom line: in an adverse possession case, the adverse possessor must be able to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that they had a good faith belief they had a right to the disputed property. This should not be a problem in a run-of-the-mill boundary line dispute case where the parties genuinely did not know about the encroachment until it is revealed years later (for example Conliff v. Hudson, 60 So. 3d 203 (Miss. Ct. App. 2011)). However, a client who has long possessed the property and either knows they have no ownership interest in the property or learn, before the 10 years runs, that they are not the owner of the property, will not be able to establish the “claim of title” element of adverse possession.

Posthumously Conceived children

September 24, 2024 § 1 Comment

With advances in technology, babies can now be created without sexual intercourse. The use of assisted reproductive technology has been increasing. In 2021, 2.3% of infants born in the United States were conceived with assisted reproductive technology. Under traditional law, if a child was not in utero at the time of the parent’s death – they were not considered the child of the deceased. Today, however, a deceased person can be the biological parent of a child long after their death.

Children conceived by assisted reproductive technology raise unique challenges for the traditional inheritance system. First, the parent who predeceased before the child was conceived may have no knowledge that their biological material would be used to assist in reproduction, and therefore may not want the after born child to have a share of their estate. Second, any inheritance that is provided for the child will diminish the amount that is taken by children who were born or conceived prior to the parent’s death, and could disrupt the orderly administration of the estate if there are no limitations on how long after the parent’s death a child can be conceived.

The issue is how to balance the competing concerns between the innocent child, the deceased’s interest in controlling where their property goes, and the efficient administration of estates. It should be noted that the outcome impacts issues beyond the inheritance system itself. Survivorship rights are often determined by whether the person has the right to inherit under a state’s descent and distribution law. The Social Security Administration considers a posthumously conceived child as a non-marital child who is only entitled to benefits if they are entitled to inheritance rights under state intestacy law.

In 2024, Mississippi adopted House Bill 1542 that sets out the rights of children conceived by assisted reproductive technology (methods of conception without sexual intercourse). The law provides that children born through assisted reproductive technology can inherit a child’s share of the deceased parent’s personal property if certain procedures are followed. The law is tilted the Chris McDill law in memory of Chris McDill. McDill was diagnosed with cancer and he and his wife Katie were unable to conceive before his death. Katie subsequently had a child through IVF, but was not able to claim survivor benefits through the Social Security Administration because the child was not entitled to inherit under Mississippi law.

First, the parent must have died without disposing of all of their personal property. Therefore, a posthumously conceived child’s rights are solely in personal – not real – property. Furthermore, if the deceased has disposed of all of their personal property in a will to someone other than the posthumously conceived child – the subsequently born child is not entitled to inherit.

Next, there must be a document signed by the deceased parent and the person that is planning on using the genetic material that the now-deceased parent consented to the use of genetic material in assisted technology after their death. The requirement that there be a record of consent from the deceased parent is to recognize and respect the reproductive desires of the deceased.

After death, the personal representative and the court must have been given notice or had actual knowledge of the intent to use genetic material in assisted reproduction not later than six months after the death of the parent. Thereafter, the embryo must be in utero not more than thirty-six months after the parent’s death, and the child must be born not later than forty-five months after the parent’s death and must live 120 hours after birth. The purpose of setting this time frame is to give the surviving parent an opportunity to grieve and contemplate whether to use the genetic material while, at the same time, ensuring that the estate will not remain open indefinitely.

If the deceased was divorced or legally separated from the individual seeking to use the genetic material, there is a rebuttable presumption that the decedent did not consent to use of their genetic material in assisted reproductive technology.

If the requirements above are satisfied, the court shall set aside a child’s share of the qualifying personal property. Each qualifying child would share in that child’s share of the estate. The court should then distribute the remainder of the estate as provided by law of descent and distribution and close the estate for all purposes except distribution of the set-aside property. Once the eligible children (born and survive 120 hours) are ascertained, the court should distribute the set-aside property to those children. If there are no eligible children, the court should distribute the estate according the descent and distribution statute. The statute expressly provides that it is the intent of the law that “an individual deemed to be living at the time of the decedent’s death” under the statute would qualify for federal survivor benefits.

June 15, 2020 § 30 Comments

As I mentioned here before, today’s is the final post on this blog, except as I mention below.

All of the content posted up to now will remain at this address for your ready access unless WordPress changes the rules to something intolerable, in which case I will try to let you know before disappearance takes place.

Please remember that the law changes all the time, so when you read that post from 2012 and think “Aha! Just the case I’ve been looking for!” it may be that it is no longer good law. This site has never been intended as a substitute for solid research.

Several people have asked me to replace my 4x/week posts with occasional pieces. Well, that would be more of a nuisance to readers trying to keep up than something helpful. I may share some of my photos from time to time. I’m no Ansel Adams or William Eggleston, or even Vivian Maier, but I do enjoy my cameras and I enjoy sharing my pictures.

There is a move afoot to create a chancery practice site. I don’t know whether it will be a static site, or a blog, or what form it ill take, but if you will support it, you will benefit.

More than 65% of my life has been dedicated to the law, the past 14 as chancellor. Despite all its shortcomings, I think the law is the noblest profession. My passion as judge has been to heighten professionalism and the level of practice. I hope this blog served that purpose.

So, thank you for letting me try to enlighten and entertain you these past ten years. It’s been an enjoyable experience. I have enjoyed getting to meet in person and by comment many lawyers I would never have crossed paths with otherwise.

Reprise: The Vital Importance of Checklists

June 10, 2020 § 1 Comment

Reprise replays posts from the past that you might find useful today.

Trial Factors aka “Checklists”

March 6, 2018 § Leave a comment

The MSSC threw down the gauntlet in 1983 in Albright v. Albright, mandating that trial judges must make findings of fact as to certain specific factors when making an award of child custody.

Since then, the number of factor-driven cases has multiplied. There are 13 now, by my count.

I call it “Trial by checklist” because you can reduce every list of factors to a convenient checklist that you can use at trial. I suggest you copy these checklists and have them handy in your trial materials. Build the outline of your client’s case around them. In your trial preparation design your discovery to make sure that you will have proof at trial to support findings on the factors applicable in your case. Subpoena the witnesses who will provide the proof you need. Present the evidence at trial that will support the judge’s findings.

If you don’t put on proof to support findings of fact by the chancellor, your case will fail, and you will have wasted your time, the court’s time, your client’s money. You will have lost your client’s case and embarrassed yourself personally, professionally, and, perhaps, financially.

If the judge fails to address the applicable factors in his or her findings of fact, file a timely R59 motion asking the judge to do that, because failure to make findings with respect to the applicable factors is cause for remand — an expensive do-over. But remember — and this is critically important — if you did not put the proof in the record at trial to support those findings, all the R59 motions in the world will not cure that defect.

Here is an updated list of links to the checklists I’ve posted:

Income tax dependency exemption.

Modification of child support.

Periodic and rehabilitative alimony.

I try to remind folks twice a year about the importance of using checklists in making your cases.

“Quote Unquote”

June 5, 2020 § Leave a comment

Reading

May 22, 2020 § Leave a comment

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The title refers to the golden rising-sun emblem on the national flag of the short-lived (1967-1970) Republic of Biafra (Bee-afra) that seceded from Nigeria, prompting a bloody tribal civil war in which millions were slaughtered and starved to death, and this is a story of that era. We see the unfolding events through several characters, including a professor, twin sisters from a patrician family, a house servant, an Englishman, and their interactions with each other and various minor figures. Adichie is a skilled storyteller adept at developing character, and she has a keen eye for description that she deftly crafts into entertaining prose. Fiction.

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan. Pulitzer-Prize-winning “novel” that is actually a set of 13 discrete stories through which many of the same characters weave in and out as time oscillates from story to story between the present, past, and even future. The style and voice vary from chapter to chapter, rewarding the reader with a kaleidoscope of expression and points of view. Not only is the structure of the novel unorthodox, but in one chapter Egan adroitly describes a family’s interrelationships through a teenager’s power-point presentation. The writing is bright and crisp, the characters vivid and sharply drawn. Highly recommended. Fiction.

Calypso by David Sedaris. Yet another collection of amusing essays. We have come to expect laugh-out-loud passages in Sedaris’s work, and there are some here. But his reflections in this book on aging, his father, and his siblings sound a more somber, reflective tone. Still, if you enjoy Sedaris, you will enjoy this collection. Fiction or non-fiction; you decide.

Never Enough by Judith Grisel. A PhD neuroscientist and former addict explains addiction from a scientific and experiential point of view. If you’re like me, you will skim the chemistry and get right to the explanations of how addiction occurs, how different substances have different effects, and what is and is not effective treatment. Non-fiction.

A Different Drummer by William Melvin Kelly. A lost treasure, first published in 1962, but largely overlooked and overshadowed as civil-rights confrontations were beginning to grab headlines and attention. Rediscovered and republished in 2018, it is the story of a fictional southern state located between Mississippi and Alabama, and the exodus of its black inhabitants. Kelley, who was black (he died in 2017), tells the story from the viewpoint of the white people who become enraged over the development, with predictable results for that era. Fiction.

The Winter Soldier by Daniel Mason. An Austrian medical student joins the army of the Holy Roman Empire in World War I and is assigned to a field hospital in Hungary where he falls in love with a mysterious nun serving as a nurse. Mason’s writing sparkles, but the plot is thin to the point of transparency, and the book tends to plod toward its finish. Fiction.

An Unexpected Life by Mary Ann Connell. A bored housewife surreptitiously enrolls in law school against her husband’s wishes and goes on to become house counsel for the University of Mississippi, guiding the school through some of its most momentous legal challenges. This book is a Mississippi Who’s Who of the 60’s through the 2000’s, but more significantly is the tale of an indomitable spirit. A native of Louisville and daughter of a small-town lawyer, Connell’s poignant childhood molded her into an overachiever who relentlessly pursued education and excellence. Non-fiction.

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. The remarkable story of the great migration of blacks from the south to the north from 1915-1970. Told through the lens of three emigrants, one from Mississippi, another from Louisiana, and the third from Florida, the book details the struggles, poverty, and oppression that drove them to seek better fortunes in Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. They found greater freedom and prosperity, but experienced more discrimination and diminished opportunity than they expected. Woven through the stories of the three is the greater story of the millions who were a part of the mass movement. Non-fiction.

The Jersey Brothers by Susan Mott Freeman. Three brothers from New Jersey enlist in the Navy in World War II. One is stationed in the Phillippines when the islands are overrun by the Japanese and he is taken prisoner. This is the story of the family’s quest to find him. Non-fiction.