SYMPATHY FOR THE DEVIL

December 12, 2010 § 8 Comments

Curtis Wilkie’s THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS is the story of the rise and fall of powerful trial lawyer Dickie Scruggs. It is entertainingly well written, as one would expect of an author with Wilkie’s gift for the word, and microscopically researched. Wilkie’s book complements KINGS OF TORT, Alan Lange’s and Tom Dawson’s treatment of Scruggs’ downfall from the prosecution point of view. Those of you who savor Wilkie’s keen writing and incisive journalism will not be disappointed by this book. The subject matter is a must-know for all Mississippi lawyers and jurists, and citizens as well. I recommend that you buy and read this book.

Curtis Wilkie’s THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS is the story of the rise and fall of powerful trial lawyer Dickie Scruggs. It is entertainingly well written, as one would expect of an author with Wilkie’s gift for the word, and microscopically researched. Wilkie’s book complements KINGS OF TORT, Alan Lange’s and Tom Dawson’s treatment of Scruggs’ downfall from the prosecution point of view. Those of you who savor Wilkie’s keen writing and incisive journalism will not be disappointed by this book. The subject matter is a must-know for all Mississippi lawyers and jurists, and citizens as well. I recommend that you buy and read this book.

Although I commend Wilkies’s book to you, I do find it troubling that it is unabashedly sympathetic to Scruggs. Wilkie finally acknowledges their friendship at page 371, the third-to-last page of the book.

As a member of the legal profession for nearly four decades and a member of the judicial branch, I can find no sympathy whatsoever for Scruggs at this stage of his life. His flirtations with unethical conduct and illegality are legion. Even his acolyte (Stewart Parrish’s excellent descriptive), Tim Balducci, said in a candid moment that his approach to corruptly influence judge Lackey was not his “first rodeo” with Scruggs, and that he knew “where all the bodies are buried.” Big talk? Perhaps. But to me it eloquently bespeaks Scruggs’ history: His involvement at the shadowy edges of Paul Minor’s illegal dealings with Judges Wes Teel and John Whitfield; his use of stolen documents in the tobacco litigation; his use of questionably acquired documents in the State Farm litigation; and the hiring of Ed Peters to influence Judge Bobby Delaughter. Are there more?

Wilkie suggests that Scruggs’ increasing dependence on pain-killer medication led him to fall carelessly into a trap laid for him and Balducci by a scheming Judge Lackey, who had it in for Scruggs because of Scruggs’ political attacks on Lackey’s friend George Dale. He posits that Lackey created the crime, and that Scruggs had set out initially “only” to improperly influence Lackey.

The pain killers may be a contributing reason, but even a first-year law student knows that is not an excuse.

What about the idea of a trap? I leave it to lawyers far better versed in criminal law and procedure to address that. To me, the issue is finally resolved in this sentence on page 337: “But Scruggs had acknowledged, ‘I joined the conspiracy later in the game.'” Case closed as far as I am concerned. Moreover, Scruggs was not an unsophisticated convenience store owner charged with food stamp fraud. He was a sophisticated, powerful lawyer skilled in manipulating the levers of legal machinery. He was not a gullible rube who did not grasp the significance of his actions or their consequences. He was a lawyer and as such was held to the highest standard of propriety vis a vis the judiciary, a standard he trod into the mud.

As for Judge Lackey, the author skillfully excerpts quotes from the judge’s testimony to support his charge that Lackey had an animus against Wilkie’s friend, in particular the judge’s use of the term “scum” to describe Scruggs. From my perspective, I can understand how someone in Lackey’s position would view the arrogant and powerful lawyer as scum when he saw how Scruggs had seduced the star-struck young Balducci, whom Lackey liked, into impropriety and, indeed, illegality. Some of Dickie’s and Curtis’ influential and powerful friends in Oxford may buy Wilkie’s and Scruggs’ attempt to tar Judge Lackey, but I do not. Judge Lackey chose to stay on the side of right and Scruggs chose the other side. The point goes to the judge.

Scruggs’ plaint that he only intended to commit an unethical act, not a crime — in other words that the consequences were unintended — is a familiar theme in history. Henry II of England griped to his knights that he was irked by that troublesome bishop, Thomas Becket. The knights, knowing from experience how far they could go before incurring the wrath of their king, promptly rode to Canterbury and rid their sovereign of that meddlesome priest, killing him at the altar. Likewise, Scruggs’ knights, Balducci, Patterson, Langston, Backstrom and the others, knew the ballpark Scruggs was accustomed to playing in, and they set out with his money and influence to promote his (and their) interests in the accustomed manner of doing business.

Henry II did penance for the rest of his life for what he saw as the unintended consequences of his actions. Will Scruggs try to redeem himself for the damage he did to the legal profession and the legal system? Time will tell. When he is released from prison, he could find ways to devote some of his hundreds of millions of dollars to improving the courts and the legal profession and restoring integrity to the profession that made him rich. In the final decades of his lfe, he could become known as a philanthropist who advanced the law and the legal profession, with his past a footnote. I hope that is what he does.

Read this book and judge it yourself. You may see it differently than I. The story, though, and its lessons, are important for Mississippians to know and understand.

VOICES FROM THE ABYSS

October 11, 2010 § Leave a comment

It was for only a dozen years that Adolf Hitler held power by political means in Germany and by conquest over much of Europe. Yet, in that relatively brief span of time, the Nazi regime that he masterminded managed to plunge the entire world into an abyss of degradation, terror, inhumanity and conflict so barbarous that we can scarcely imagine its scope and depth 65 years after its end.

I recently read or re-read three books dealing with life in Nazi Germany during the Hitler years.

The first is WHAT WE KNEW: TERROR, MASS MURDER AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN NAZI GERMANY by Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband. If you click on the picture to the left, it will take you to Amazon.com where you can read excerpts.

The first is WHAT WE KNEW: TERROR, MASS MURDER AND EVERYDAY LIFE IN NAZI GERMANY by Eric A. Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband. If you click on the picture to the left, it will take you to Amazon.com where you can read excerpts.

What makes this book a fascinating read is the first 250 or so pages, consisting of oral histories related by people who lived through the Nazi terror. Interviewees include: Jews who left Nazi Germany before Kristallnacht and those who left after; Jews who were deported; Jews who went into hiding; Germans who knew little about mass murder; Germans who had heard about mass murder; and Germans who knew about, witnessed or participated in mass murder.

What emerges from the testimony of these survivors is an engrossing picture of what everyday life was like in Nazi Germany from around 1932 to the end of World War II.

There are the stories of Jews who managed to flee ahead of the Nazi terror, as well as that of those who were transported to the death camps, and what they did to survive there. There is the testimony of Jews who somehow managed to hide out in Germany or its subjugated states, escaping extermination. They tell persecution by the government, and of the verbal and physical abuse they suffered at the hands of ordinary Germans who had once been their friends and neighbors, as well as of the rare kind and courageous Germans who helped them, often surreptitously so as to avoid repercussions from the Nazis.

Also here is the testimony of the Germans. There are the stories of those who adored and idolized Hitler and of those who despised and resisted him to their detriment and even destruction. There are the stories, too, of those who claim they knew nothing of the systematic extermination of the Jews and of those who knew and even participated in it.

One of the enduring questions arising out of Nazi Germany is what did ordinary people know about the atrocities of the Nazis? The authors devote the remainder of the book to analyzing the data they accumulated to address that question and others such as how anti-semitism took hold under the Nazis, the extent of spying and denunciation by ordinary citizens, the scope of police persecution, and the various forms of persecution of the Jews and others selected for torment and even annihilation. Their conclusions? You will have to read the book.

It is important for Americans to know and understand how the Nazis rose to power and came so close to dominating the entire world but for the determined resistance of England and the industrial might of the United States. After all, the Nazi phenomenon did not arise out of some ignorant peasant backwater. It occurred in the country long known as the “Land of Poets and Thinkers,” the nation that gave birth to Goethe, Schiller, Kant, Beethoven, Leibniz, Einstein, Bach, Holbein, and so many other luminaries of western civilization. It was grinding depression, political instability and desperate economic straits in the lingering aftermath of World War I that opened the way for the Nazis to capture the allegiance of the German voters, who made a devil’s bargain by surrendering their freedom in exchange for stability and economic improvement.

If the Germans could cast aside their considerable legacy of civilization and embrace the barbarity and totalitarianism of the Nazis for comfort and security, who is to say that we could not fall on the same sword?

_____________________________________

I also re-read NIGHT by Elie Wiesel.

If you have never read this powerful little book (only 120 pages) written by the Nobel-prize-winning author who as a teenager wsa transported with his family to Auschwitz and then to Buchenwald, you need to put down whatever you are reading and pause to read this. This latest edition is a new translation of the original French by his wife, Marion, and purports to be closest of all editions to Wiesel’s own voice.

Other than the substance itself, what makes this book so powerful is its spare, minimalist style, pared down ruthlessly from the original Yiddish into French by the French writer François Mauriac.

The book opens in Wiesel’s hometown of Sighet, in Transylvania, where the Jewish community was warned but refused to heed an eccentric who had been briefly imprisoned by the Nazis. It goes on to recount the establishment of a Jewish ghetto in the town and the ultimate transportation to the death camps or work camps. Wiesel saw his mother and sister taken off to the gas chamber. He and his father were put to slave labor in the camp at Buna. As the war wound down and the Russians closed in on western Poland where their camp was situated, Wiesel, his father and the other inmates were forced to march in a bitter winter blizzard from Auschwitz-Buna to Gleiwitz, a march in which thousands died. Wiesel and his father survived the march, but his father contracted dysentery soon after being savagely beaten by an SS guard, and the elder Wiesel was taken off to the gas chamber. The author poignantly tells of his last conversation with his father, a passage of the book you will not soon forget.

Wiesel’s haunting retelling of the inhumanity he endured and how he survived it will live vividly in your mind long after you have read this book.

_____________________________________

The final book is MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING by Viktor Frankl, which I re-read. This little book was listed by the Library of Congress in 1991 among the 10 most influential books in the United States.

Like Wiesel’s, Frankl’s book includes his eyewitness account of the brutality and suffering that he survived as a Jewish slave/prisoner in various Nazi concentration camps. Unlike Wiesel, Frankl approaches the experience from a psychological and psychoanalytical perspective, from which he developed the theory of Logotherapy. His theory is that life has meaning in even the most apocalyptic circumstances and finding that meaning is the main motivation in life, and that we have the freedom to find our own meaning in our suffering and the unchangeable obstacles we face. The first part of the book is Frankl’s account of his experiences, and the second is his analysis of those experiences and his conclusions about their meaning.

Like Wiesel’s, Frankl’s book includes his eyewitness account of the brutality and suffering that he survived as a Jewish slave/prisoner in various Nazi concentration camps. Unlike Wiesel, Frankl approaches the experience from a psychological and psychoanalytical perspective, from which he developed the theory of Logotherapy. His theory is that life has meaning in even the most apocalyptic circumstances and finding that meaning is the main motivation in life, and that we have the freedom to find our own meaning in our suffering and the unchangeable obstacles we face. The first part of the book is Frankl’s account of his experiences, and the second is his analysis of those experiences and his conclusions about their meaning.

This is an inspirational book that rejects the notions of victimhood and determinism. It will challenge some of your own notions about how one addresses and rises successfully above the vicissitudes and misfortunes of life.

_____________________________________

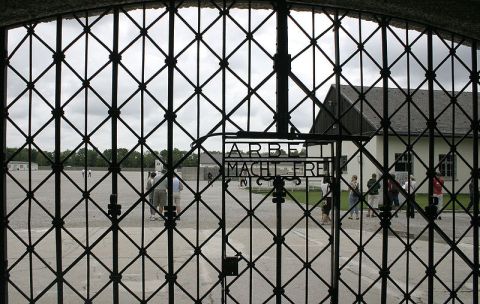

Some years ago I visited Dachau concentration camp only a few miles from Munich. The entrance gate bore the cynical epigram “Arbeit macht frei” — “Work makes you free” — the words that were copied from there and placed over the gate to Wiesel’s Auschwitz.

Dachau was not established as an extermination camp for Jews, although many Jews were imprisoned and died there. Dachau’s original and primary function was as an internment camp for political opponents of the Nazis, homosexuals and the mentally ill or erratic. Later in the war, Russian prisoners of war were transported there by the thousands, and were put to death by the bullet, some being used for target practice by the guards.

Dachau was also the site of scientific experimentation on the prisoners, which was intended to be of some military benefit. Some prisoners were put into chambers and subjected to increasing pressure until their brains literally burst out of their ears and mouths, in order to see how much pressure a human could stand. Some had organs removed and were sewn back up to see how long one could live without, say, a liver. Some had objects implanted inside of them so the effects could be observed. Some were guinea pigs for drug testing, and others were administered lethal substances to determine just how much dosage was lethal.

It was chilling to stand in the barracks where so many suffered and perished, to walk across the appelplatz where the roll call of walking dead took place every day, to see the guard towers, to stare into the crematorium where the bodies of the executed were disposed of. Gazing across the huge expanse of the camp, one could see through the barbed-wire fence the homes where German citizens of Dachau village lived their mundane lives, oblivious — they claimed — to the profound suffering and obscene atrocities taking place literally across the street.

EVER IS A LITTLE OVER A DOZEN YEARS

September 12, 2010 § Leave a comment

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

It was his children’s inquiries about their father’s childhood that led Eubanks to begin to explore the history of the dark era of his childhood. In his quest for a way to help them understand the complex contradictions of that era, he came across the files of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission and found his parents’ names among those who had been investigated, and he became intrigued to learn more about the state that had spied on its own citizens.

Eubanks’ search led him to Jackson, where he viewed the actual files and their contents and explored the scope of the commission’s activities. He had decided to write a book on the subject, and his research would require trips to Mississippi. It was on these trips that he renewed his acquaintance with the idyllic rural setting of his childhood and the small town of Mount Olive, where, in the middle of his eighth-grade school year, integration came to his school.

There are three remarkable encounters in the book. The author’s meetings with a surviving member of the Sovereignty Commission, a former klansman, and with Ed King, a white Methodist minister who was active in the civil rights movement, are fascinating reading.

The satisfying dénouement of the book is Eubanks’ journey to Mississippi with his two young sons in which he finds reconciliation with his home state and its hostile past.

If there is a flaw in this book, it is a lack of focus and detail. The focus shifts dizzyingly from the Sovereignty Commission, to his relationship with his parents, to his rural boyhood, to life in segregation, to his own children, to his problematic and ultimately healed relatiosnhip with Mississippi. Any one or two of these themes would have been meat enough for one work. As for detail, the reader is left wishing there were more. Eubanks points out that his own experience of segregation was muted because he lived a sheltered country existence, and his memories of integrated schooling are a blur. For such a gifted writer whose pen commands the reader’s attention, it is hard to understand why he did not take a less personal approach and expand the recollections of that era perhaps to include those of his sisters, or other African-Americans contemporaries, or even the white friends he had.

This is an entertaining and thought-provoking book, even with its drawbacks. I would recommend it for anyone who is exploring Mississippi’s metamorphosis from apartheid to open society.

The title of this book has its own interesting history. In June of 1957, Mississippi Governor J. P. Coleman appeared on MEET THE PRESS. He was asked if the public schools in Mississippi would ever be integrated. “Well, ever is a long time,” he replied, ” [but] I would say that a baby born in Mississippi today will never live long enough to see an integrated school.”

In January of 1970, only twelve-and-a-half years after the “ever is a long time” statement, Mississippi public schools were finally integrated by order of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, a member of which, ironically, was Justice J. P. Coleman, former governor of Mississippi.

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WAR

August 28, 2010 § 2 Comments

Through the spring and summer most of my reading has been books dealing with the South in general and Mississippi in particular in the last half of the twentieth century, the era of the struggle for civil rights I still have a few more to read on the topic before I move on to other interests.

One of the seminal events of the civil rights era was the admission of James Meredith as a student at the University of Mississippi in 1962. The confrontation at Ole Miss between the determined Meredith, backed by the power of the federal government, and Mississippi’s segregationist state government culminated in a bloody battle that resulted in two deaths and a shattering blow to the strategies of “massive resistance,” “interposition,” and “states rights” that had been employed to stymie the rights of black citizens in our state.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Lambert, who is a professor of history at Purdue University, not only was a student at Ole Miss in 1962 and an eye-witness to many of the events, he was also a member of the undefeated football team at the time, and his recollection of the chilling address delivered by Governor Ross Barnett at the half-time of the Ole Miss-Kentucky football game on the eve of the battle is a must-read.

This is a small book, only 193 pages including footnotes and index, but it is meticulously researched. As a native Mississippian and eyewitness, Lambert is able not only to relate the historical events, he also is able to describe the context in which they happened.

The book lays out the social milieu that led to the ultimate confrontation. There is a chapter on Growing Up Black in Mississippi, as well as Growing up White in Mississippi. Lambert describes how the black veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict had experienced cultures where they were not repressed because of their race, and they made up their minds that they would challenge American apartheid when they returned home. Meredith was one of those veterans, and he set his sights on attending no less than the state’s flagship university because, as he saw it, a degree from Ole Miss was the key to achievement in the larger society. He also realized that if he could breach the ramparts at Ole Miss, so much more would come tumbling down.

The barriers put up against Meredith because of his race were formidable. He was aware of the case of Clyde Kennard, another black veteran who had tried to enroll at what is now the University of Southern Mississippi, but was framed with trumped-up charges of stolen fertilizer and sentenced to Parchman, eventually dying at age 36. And surely he knew of Clennon King, another black who had managed to enroll at Ole Miss only to be committed to a mental institution for his trouble. Even among civil rights leadrs, Meredith met resistance. He was discouraged by Medgar and Charles Evers, who were designing their own strategy to desegregate Ole Miss, and felt that Meridith did not have the mettle to pull it off. Against all of these obstacles, and in defiance of a society intent on destroying him, Meredith pushed and strove until at last he triumphed.

But his triumph was not without cost. Armed racists from throughout Mississippi, Alabama and other parts of the South streamed to Oxford in response Barnett’s rallying cry for resistance. The governor’s public rabble-rousing was cynically at odds with his private negotiations with President John Kennedy and US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, with whom he sought to negotiate a face-saving way out. The ensuing battle claimed two lives, injured 160 national guardsmen and US marshals, resulted in great property damage, sullied the reputation of the university, tarred the State of Mississippi in the eyes of the world, led to armed occupation of Lafayette County by more than 10,000 federal troops, and forever doomed segregation. Ironically, the cataclysmic confrontation that Barnett and his ilk intended to be the decisive battle that would turn back the tide of civil rights was instead the catalyst by which Ole Miss became Mississippi’s first integrated state university. It was in essence the final battle of the Civil War, the coup de grace to much of what had motivated that conflict in the first place and had never been finally resolved.

As for Meredith, the personal cost to him was enormous. He was subjected to taunts and derision, as well as daily threats of violence and even death. He found himself isolated on campus, and did not even have a roommate until the year he graduated, when the second black student, Cleveland Donald, was admitted. Meredith described himself in 1963 as “The most segregated Negro in the world.”

The admission of James Meredith to Ole Miss not only opened the doors of Mississippi’s universities to blacks, it also helped begin the process in which Mississippians of both races had to confront and come to terms with each other as the barriers fell one by one. As former mayor Richard Howorth of Oxford recently told a reporter: ” … other Americans have the luxury of a sense of security that Mississippi is so much worse than their community. That gives them a sense of adequacy about their racial views and deprives them of the opportunity we’ve had to confront these issues and genuinely understand our history.”

Meredith’s legacy is perhaps best summed up in the fact that, forty years after his struggle, his own son graduated from the University of Mississippi as the Outstanding Doctoral Student in the School of Business, an event that Meredith said, ” … vindicates my entire life.” His son’s achievement is the culmination of Meredith’s singular sacrifice. What Meredith accomplished for his son has accrued to the benefit of blacks and whites alike in Mississippi, and has helped our state begin to unshackle itself from its slavery to racism.

OLD TIMES HERE ARE NOT FORGOTTEN

August 13, 2010 § 2 Comments

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” — William Faulkner in REQUIEM FOR A NUN

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” — L.P. Hartley in THE GO-BETWEEN

No region of our nation has revered, understood, embraced, been bedevilled by and romanticized its past more than has the South. Much of the South’s history since the Civil War has been the history of evolving race relations in a culture determined to preserve inviolate its notion of its past. Beginning in the 1950’s, however, the irresistable force of change in the form of the civil rights movement collided head-on with the immovable object in the form of “massive resistance,” and the resulting explosion that destroyed the foundation of segregation began the transformation of southern culture that continues to this day.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

On its face, DIXIE is a history of the South’s agonizing journey through the watershed era of the civil rights movement and into the present, a chronicle of the events that shook and shattered our region and sent shock waves across the nation. The events and figures parade across his pages in a comprehensive panorama: The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Meredith and the riot at Ole Miss, Ross Barnett, Jimmy Carter, Eudora Welty, Brown v. Board of Education, Freedom Summer, Aaron Henry, the Ku Klux Klan, the struggle for control of the Democratic Party in Mississippi, White Citizens Councils, sit-ins, John Bell Williams, William Winter, Willie Morris, Charles Evers, Byron de la Beckwith and Sam Bowers, Trent Lott and Thad Cochran, William Waller, the riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968, and more. As a history of the time and how the South tore itself out of the crippling grip of the past, the book is a success.

The great charm and charisma of this book, however, is in the way that Wilkie weaves his own, personal history through the larger events, revealing for the reader how it was to be a southerner in those days, both as an average bystander and as an active participant.

The author grew up in Mississippi, hopscotching around the state until his mother lighted in the town of Summit. His recollection of life in the late 40’s and 50’s in small-town Mississippi echoes the experiences of many of us who were children in those years, and will enlighten those who came along much later.

Wilkie was a freshman at Ole Miss when James Meredith enrolled there in 1962, sparking the riot that ironically spurred passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. On graduation Wilkie took a job with the Clarksdale newspaper and developed many contacts in Mississippi politics that eventually led him to be a delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, where he was an eyewitness to the calamitous events there.

Through a succession of jobs, Wilkie wound up a national and middle-eastern corresondent for the BOSTON GLOBE, and even a White House Correspondent during the Carter years. His observations and first-hand accounts of his personal dealings with many of the leading figures of history through the 60’s and 70’s are fascinating.

When he had left the South, Wilkie believed he was leaving behind a tortured land where change could never take place, and where he could never feel at home with his anti-racism views and belief in racial reconciliation. He saw himself as a romantic exile, a quasi-tragic figure who could never go home again, but over time he found the northeast lacking, and he found the South tugging at him whenever he returned on assignment.

When his mother became ill, Wilkie persuaded his editor to allow him to return south, and he moved to New Orleans, from where he covered the de la Beckwith and Bowers Klan murder trials and renewed his acquaintanceship with many Mississippi political and cultural figures, including Willie Morris, Eudora Welty and William Winter. He began to discover that the south had undergone a sea change in the years that he was away, and that the murderous, hard edge of racism and bigotry had been banished to the shadowy edges, replaced largely by people of good will trying their best to find a way to live together harmoniously. He found a people no longer dominated by the ghosts of the ante-bellum South.

In the final chapter of the book, Wilkie is called home for the funeral of Willie Morris, and the realization arises that he is where he needs to be — at home in the South. His eloquent end-note answered a question Morris had posed to him some years before: “Curtis, can you tell us why you came home?” Wilkie’s response:

Just as Vernon Dahmer, Jr. had said, I, too believe I came home to be with my people. We are a different people, with our odd customs and manner of speaking and our stubborn, stubborn pride. Perhaps we are no kinder than others, but it seems to me we are … We appreciate our history and recognize our flaws much better than our critics. And like our great river, which overcomes impediments by creating fresh channels, we have been able in the span of Willie’s lifetime and my own to adjust our course. Some think us benighted and accursed, but I like to believe the South is blessed with basic goodness. Even though I was angry with the South and gone for years, I never forsook my heritage. Eventually, I discovered that I had always loved the place. Yes, Willie, I came home to be with my people.

Those of you who lived through the troubled years recounted here will find that Wilkie’s accounts bring back memories that are sometimes painful and sometimes sweet. For readers who are too young to recall that era, this book is an excellent history as well as an eye-opening account of what it was like to grow up in that South.

Wilkie’s new book, THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS, about the Scruggs judicial bribery scandal, is due out in October.

TWILIGHT OF THE GODS

July 25, 2010 § 2 Comments

They were so powerful that they thought they were gods, immune from the misfortunes of mere mortals. They were Dickie Scruggs and all of his allies and fellow-travelers who rose to unparalleled power and wealth through bribery and corruption, until their un-god-like downfall. Their story is an epic Mississippi saga.

They were so powerful that they thought they were gods, immune from the misfortunes of mere mortals. They were Dickie Scruggs and all of his allies and fellow-travelers who rose to unparalleled power and wealth through bribery and corruption, until their un-god-like downfall. Their story is an epic Mississippi saga.

The next book on the grotesquerie of Dickie Scruggs and his ilk will be out soon. THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS, by Mississippian Curtis Wilkie, former BOSTON GLOBE foreign correspondent and current Ole Miss professor, is set to be released October 19, 2010, and the author will be at Square Books in Oxford that day to talk about his book and autograph copies.

Author Richard Ford made these comments about the book on the Square Books web site …

Addictive reading for anyone interested in greed, outrageous behavior, epic bad planning and character, lousy luck, and worst of all, comically bad manners. Wilkie knows precisely where the skeletons, the cash boxes and the daggers are buried along the Mississippi backroads. And he knows, ruefully — which is why this book demands a wide audience — that the south, no matter its looney sense of exceptionalism, is pretty much just like the rest of the planet.

I reviewed Alan Lange’s and Tom Dawson’s book on the Scruggs downfall here.

ATTICUS FINCH FIFTY YEARS LATER

July 15, 2010 § 1 Comment

He had an unremarkable law practice in the backwater town of Maycomb, Alabama, in the 1930’s. He was a widower with two small children to raise, an earnest son named Jem and a tomboyish daughter named Scout. In one steaming southern summer his bravery and devotion to the rule of law elevated him into one of the most towering exemplars of integrity and the best of the legal profession. And yet, he never existed in real life. His name is Atticus Finch, hero of Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, which observes the 50th anniversary of its publication this week.

The book is a powerful evocation of small-town life in the south in the sleepy, destitute era long before the civil rights awakening of the 1960’s. Rosa Parks had not yet sat in the front of a bus in Montgomery. There were no freedom riders then. No protest marches with German Shepherds and fire hoses. In the time of the story there is no political movement bearing the characters forward; there is only a black man wrongly accused and this small-time lawyer in a “tired, old” Alabama town doing what his profession and his own personal convictions demanded of him, and doing it with honor, courage and single-minded devotion to the interest of his client, heedless of the personal danger that his unpopular actions brought him. And through it all Atticus Finch the lawyer was a wise, attentive and devoted father and rock for his children.

To many of us, Atticus Finch is inescapably Gregory Peck, who played the role in the 1962 film and won an Oscar as best actor. The movie won three Academy Awards out of eight nominations, and today is considered one of the great American classics. Its black-and-white images remain etched in our minds. I am sure that I am not the only southern teenager who saw the movie in those days and was inspired to be a lawyer just like Atticus some day.

To many of us, Atticus Finch is inescapably Gregory Peck, who played the role in the 1962 film and won an Oscar as best actor. The movie won three Academy Awards out of eight nominations, and today is considered one of the great American classics. Its black-and-white images remain etched in our minds. I am sure that I am not the only southern teenager who saw the movie in those days and was inspired to be a lawyer just like Atticus some day.

Half a century after he appeared, Atticus Finch remains a model and a contemporary inspiration. In a recent poll practicing lawyers voted him an influence on their careers; strong stuff for a fictional character.

Here is Atticus Finch in his own words:

- “Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy… but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

- “The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box.”

- “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

- “The one thing that doesn’t abide by majority rule is a person’s conscience.”

- “There’s a lot of ugly things in this world, son. I wish I could keep ’em all away from you. That’s never possible.”

- “Courage is not a man with a gun in his hand. It’s knowing you’re licked before you begin but you begin anyway and you see it through no matter what. You rarely win, but sometimes you do.”

- “When a child asks you something, answer him, for goodness sake. But don’t make a production of it. Children are children, but they can spot an evasion faster than adults, and evasion simply muddles ’em.”

- “Bad language is a stage all children go through, and it dies with time when they learn they’re not attracting attention with it.”

- “Best way to clear the air is to have it all out in the open.”

HELLHOUND ON HIS TRAIL

July 11, 2010 § 2 Comments

1968 was a hellish year on many counts for our nation. It was the year that Bobby Kennedy was gunned down at a primary night victory celebration in California. The Vietnam War continued its grip on the nation and claimed Lyndon Johnson’s presidential career among its 50,000-plus casualties. The Democratic convention in Chicago was beset by violent demonstrations and police reaction that were broadcast live on television to the shock of millions. The heady “Prague Spring” came to a stunning and abrupt end when Soviet tanks rumbled into Czechoslovakia and crushed the fresh democracy that had sprung up, raising new fears of an east-west confrontation and adding to the chilly pall that the cold war had cast over our lives for more than twenty years.

But no event in the tumult of 1968 had more powerful repercussions than the assasination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., on April 4, in Memphis.

Hampton Sides’ book, HELLHOUND ON HIS TRAIL is the meticulously researched and spellbinding retelling of how the drifter James Earl Ray stalked King, planned the murder, and carried it out, and the story of how the FBI, Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Scotland Yard painstakingly unravelled the knot of aliases and false trails that Ray threw in their path until his arrest at a London airport two months after the assasination.

There is nothing really new here: no startling bombshell revelation of a conspiracy that has long been whispered about; no new eyewitness or piece of hitherto undiscovered shard of evidence; no new insight into the enigmatic Ray.

What is here in this book, and what makes it such a compelling read is how Sides lays it out like a detective novel, unfolding developments and clues in tantalizing morsels that whet the reader’s appetite and keep the pages turning for more. Sides draws on the many reams of investigative material, research, scholarly papers and personal interviews that rose out of this dark event and applies his considerable writing skill to craft a narrative that is hard to put down.

The characters are all here in bold relief: King himself, struggling to re-establish himself and non-violence as pre-eminent in the civil rights movement, against the rising tide of calls to racial violence; Ray, the murderous escaped con who swore he would kill the man he considered the leader of the race he hated; Ralph David Abernathy, King’s loyal friend and aide, but ultimately unequal to the task of being his successor; Coretta, the stoic widow; J. Edgar Hoover, who hated King and resisted taking over the murder investigation until he was ordered to do so by US Attorney General Ramsey Clark; Jesse Jackson, who would lie to try to claim the mantle of King’s successor; the FBI agents who undertook a seemingly impossible task and did a remarkable job of tracking down the killer in the largest manhunt in history; and the cast of casual bystanders who were caught up in the events. And, yes, there are some tawdry details about King’s personal life; those are an undeniable part of the true story.

Hampton Sides is a native Memphian with a good feel for the south. Despite the fact that he was only six years old when King was murdered, Sides is able to paint the landscape of racism and insensitivity to poverty that permeated the region in those days without resorting to the stereotypes and generalizations on which writers unfamiliar with southern folkways of the 1960’s so often fall back. His depiction of the south of 1968 is factual and stark. We thought we had come so far back then, but in retrospect some of the images are painful. There were Cal Alley’s racist and patronizing cartoons that I recall reading in the Memphis Commercial Appeal in those days. There is the depiction of the regal Cotton Carnival and its opulence set against the desparate poverty of the Memphis sanitation workers. There is the fact that racist groups raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for Ray’s defense and hailed him as a hero, a sobering reminder of a seamy underside of American society.

Reading this book will bring into focus how much America and the south have changed in 42 years. African-Americans are more incorporated into the mainstream now, in jobs, neighborhoods, schools and elected positions that were unimaginable in 1968. African-Americans are a growing segment of the middle class. It is not uncommon to see whites and blacks socializing together, something so innocuous today that would have raised eyebrows back then. Racial reconciliation is not an accomplished fact, but we have made a start thanks to the life and sacrifice of a man whose life was cut short by the very violence he repudiated.

THE MARK OF THE BEAST

July 1, 2010 § 12 Comments

And he causeth all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and bond, to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads; And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark, or the name of the beast, or the number of his name. Here is wisdom. Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore and six. Revelations 13:16-18.

666. The number of the mark of the beast.

Irony of ironies, that is the section of the federal criminal code under which Dickie Scruggs and his cohorts were indicted for the crime of corruptly influencing a public official. 18 U.S.C. §666.

And so it was that Dickie Scruggs and his minions, bearing the mark, bought and sold justice in Mississippi.

I have read KINGS OF TORT by Alan Lange and Tom Dawson, the enthralling story of how Dickie Scruggs and Paul Minor, in league with others, corrupted our legal system. The story is stomach-turning and fascinating at the same time, in the same way that one is revolted by seeing a person leap to his death from a tall building, yet can not look away. It is a story that will repel and anger honest lawyers and judges, and yet it is one that they must know. I feel strongly that it is a must-read for anyone who has practiced law or sat the bench in Mississippi, as well as anyone else who is interested in our state legal system.

KINGS OF TORT is the story of the rise and fall of some of the richest and most powerful lawyers ever known in Mississippi, and indeed in our republic, along with the judges they corruptly influenced. They are all here: Dickie Scruggs, Zach Scruggs, Paul Minor, Bobby DeLaughter, Joey Langston, Sid Backstrom, Tim Balducci, John Whitfield, Wes Teel, Ed Peters, Steve Patterson and others who, for money, or out of lust for power and control, or for sheer egotism, stole from one another and tried to manipulate and corrupt the legal system to achieve their ends. It’s all too unfortunately true, and it happened here in our state during our careers as we went about our quotidian legal tasks, unmindful of the cesspool growing only a few miles down the road that would engulf so many.

Authors Alan Lange and Tom Dawson each had a favored vantage point from which to view this Greek tragedy, act by act. Lange amassed literally tons of information on the various scandals by his untiring reporting on his blog, Y’all Politics. Dawson was one of the lead prosecutors in the Oxford U.S. Attorney’s office who helped design the strategy that brought down the Scruggs house of cards, from coordinating FBI investigation and search warrants to drafting the indictments and preparing for trial.

The downfall of Dickie Scruggs was a national story, reported as it unfolded in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Several Mississippi-based blogs followed the story closely and actually served as sources for the national press. Lange’s own Y’all Politics was a major player in revealing much information. Folo, now in hiatus, was energetic in pursuing the story, often breaking news that others missed, and one of its most astute contributors, NMC (who is Oxford atty Tom Freeland), continues with his own blog, NMissCommentor.

The improbable hero of this sordid saga is District 3 Circuit Judge Henry Lackey of Calhoun City, who toppled the kings of tort from their thrones by going to the U.S. Attorney and reporting that they were attempting to bribe him. He then wore a wire and captured the crucial evidence that first snared Balducci, and then took down Scruggs, Backstrom, Patterson and Langston. Judge Lackey is an engaging and self-effacing man with a wry humor. When the prosecutors warned him of the stress that his role as undercover witness would place on him and his heart problems, he smiled and said with country assurance, “Boys, don’t mind the mule, just load the wagon.” He would be the first to disclaim the hero label, pointing out that he only did what his oath and judicial ethics expected of him.

Most readers will find the writing in large part clear and easy to read. The authors do a good job of explaining complicated legal proceedings and concepts in a way that non-lawyers can easily grasp. What is unfortunately lacking in a book such as this with national exposure, however, is decent editing. It is bothersome that the writers appear not to know the difference between “affect” and “effect,” or that the correct pronoun to refer to a person is “who” rather than “that” (e.g., “He is the person that who loaned the money”), or that “tortuous” does not mean the same thing as “tortious,” or that the word “divulge” does not mean “deprive,” or that proper usage is “between him and … ” and not “between he and … “, or that the court room of the Calhoun County Court House is in Pittsboro and not Calhoun City, and that some of the clauses within clauses will make your head spin. Good editing would have cured those defects. Warts and all, though, it’s still a worthwhile and even essential read for Mississippi lawyers.

Buy this book and keep it in your law office library. Keep it handy. When you feel an itch to stretch ethical limits, even ever so slightly, to score big in a case, or to gain an upperhand, or you feel the temptation to shaft another lawyer who has been loyal and helpful to you, pull this book off the shelf and hold it. Remember those lawyers and judges marked with the number of the beast and ask yourself: “Do I really want to be like them?”