FREEDOM SUMMER IN MERIDIAN

May 23, 2011 § 17 Comments

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Riders’ attempts at integration of transportation and amenities across the south. The arrival of the Freedom Riders in May, 1961 was met with mob violence and police brutality, but it did not end segregation in Mississippi. The Freedom Riders did, however, pique public awareness across the nation of the inequalities in the south and the need to address them.

In 1962, representatives of four civil rights organizations — SNCC (Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee), CORE (Congress of Racial Equality), NAACP and SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) — met at Clarksdale and formed a new organization designed to coordinate their efforts and resources in Mississippi. They called the organization COFO (Congress of Federated Organizations).

The primary concern was to register black voters in Mississippi. At the time, Mississippi at less than 7% had the lowest percentage of black voter registration in the nation. Blacks seeking to register to vote were subjected to poll taxes, examinations that they had to pass to become enfranchised, and, when that was not enough, violence and even death.

It was decided that COFO would spearhead a massive, concentrated voter registration and desegregation effort in Mississippi in the summer of 1964. Volunteers were enlisted from across the country, primarily from the northeast and midwest, many of whom were college students willing to devote a summer to the cause. The effort came to be known as “Freedom Summer.”

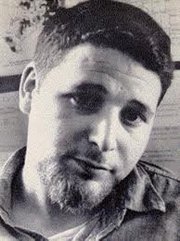

In January, 1964, Michael Schwerner came to Mississippi and opened a COFO office in Meridian at 2505 1/2 Fifth Street. Schwerner was a member of CORE, and was a native of New York. He and his wife, Rita, lived in a Meridian apartment, and engaged in various community organizing activities. The COFO office was the headquarters of the Freedom Summer operation in Lauderdale County.

The headquarters occupied the second floor of the Fielder & Brooks Drug Store, an established and respected black business.

The Schwerners opened a COFO-sponsored community center where black children could gather and play games, socialize and access a lending library.

COFO in Meridian also operated one of the several dozen Freedom Schools that were opened across Mississippi that summer. The Freedom Schools taught citizenship, black history, constitutional rights, political processes, and basic academics. More than 3,500 students attended the Freedom Schools. Meridian’s Freedom School was at the old black Baptist Seminary.

Here is the text of a 1964 COFO memo describing the Meridian operation:

Meridian is a city of 50,000, the second largest in the state. It is the seat of Lauderdale county. It is in the eastern part of the state, near the Alabama border, and has a history of moderation on the racial issue. At the present time, the only Republican in the State Legislature is from Meridian. Registration is as easy as anywhere in the state, and there is an informal (and inactive) “biracial committee”, which, if it qualifies, is the only one in the state.

Voter registration work in Meridian began in the summer of 1963 (for COFO staff people, that is), and by autumn, when Aaron Henry ran in the Freedom Vote for Governor campaign, there was a permanent staff of two people in the city. In January, 1964, Mike and Rita Schwerner, a married couple from New York City, started a community center. In Meridian’s mild political climate, the community center there has functioned more smoothly than either of the two community centers which COFO has organized in tougher areas. The center has recreation programs for children and teenagers, a sewing class and citizenship classes. It also has a library of slightly over 10,000 volumes, and ambitious plans for expansion if more staff were available. The COFO staff in Meridian uses Meridian as a base for working six other adjoining counties.

The Freedom School planned for Meridian will have a fairly large facility, in contrast to most places in the state. The Baptist Seminary is a large, 3-story building with classroom capacity for 100 students and sleeping accommodations for staff up to about 20. Besides this, there is a ballpark available for recreation. The school has running water, blackboards and a telephone. The center has a movie projector and screen which it probably would lend. The library lends books to anyone for two-week periods. The question of rent has not been decided for the school. Even if there is no rent, however, we can count on a budget of around $1300, for food for students, utilities, telephone and supplies.

One of the COFO volunteers was Mark Levy, who came to Meridian with his wife, Betty, from Queens College in New York. He chronicled his sojourn in Meridian with his camera, and his impressive collection of photographs is in the Queens College archives, where you can view it online.

A remarkable fact documented by Levy is that the famed folk/protest singer Pete Seeger visited Meridian and played at the old Mt. Olive Baptist Church during Freedom Summer.

He performed for the COFO volunteers. The next photo shows COFO workers and others joining hands to sing along with Seeger. The young woman at the right with the flowered dress is COFO volunteer Patti Miller of Iowa, who pinpoints the date of Seeger’s performance as August 4, 1964.

Shortly after he arrived, Schwerner was joined by an eager young Meridianite volunteer named James Chaney. As the summer drew near, other volunteers began to arrive from other places, among them Andrew Goodman of New York.

Despite its moderate reputation on racial issues, there was a dark underside to Meridian and the surrounding area. The Klan was active, with members in law enforcement and in influential positions. The Klan had its eye on COFO, and on Schwerner in particular. They gave him the derisive nickname “Goatee,” for his beatnik-style beard, and spread rumors that he was having an affair with a black woman.

Mississippi’s political leadership provoked the citizenry with accusations that the COFO workers were communists who had trained in Cuba. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover made the statement that “We will not wet-nurse troublemakers,” insinuating that anyone who took matters into their own hands would not be bothered by the feds.

On June 21, 1964, Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney had returned from a training session in Oxford, Ohio, to learn that the Mt. Zion Methodist Church in Neshoba County had been burned by the Klan and some of its members beaten in retribution for allowing a Freedom School to operate there. The three travelled from Meridian to Neshoba and met with the leaders of the church. As they made their way back to Meridian, the three were stopped by a Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff and taken into custody on the pretext of a speeding charge. After they were released from jail in Philadelphia, they were stopped again on Highway 19 South by the Sheriff, who allowed a group of Klansmen to take them to Rock Cut Road, between House and Bethsaida, where all three were murdered by gunfire. An historical marker is set on the junction of Highway 19 and the road where they were killed.

When the trio did not return to Meridian as scheduled, their disappearance was reported and a manhunt ensued. Hundreds of naval personnel participated. President Johnson ordered Hoover to mobilize the FBI, and the agency began investigating, increasing the number of agents in the state from 15 to more than 150. Posters went up.

The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission investigated and its reports took the prevailing view that the disappearance was a publicity stunt designed to stir up public opinion. Governor Paul B. Johnson quipped that “Those boys are in Cuba.”

Before long, the searches turned up the CORE station wagon that the men had driven from Meridian. It had been taken to the Pearl River swamps north of Philadelphia east of Stallo off of Highway 21, where it was burned.

The discovery of the car did not quell the public belief that the disappearance had been staged, but the denial, speculation and ridicule abruptly ended when the three bodies were discovered by the FBI in a dam being built not far from the Neshoba County fairgrounds. It was conclusive proof of the atrocity.

The FBI autopsy revealed that all three young men had died of gunshot wounds. The families were not convinced, however, and they demanded and got a second autopsy which revealed that Schwerner and Goodman had indeed been shot and killed. Chaney, though, had been brutally beaten before being fatally shot. The doctor who performed the autopsy said that he had never seen such extensive, catastrophic injuries, including smashed bones and damaged internal organs, not even in car or plane wreck victims.

Patti Miller remembers that that the bodies were found on August 4, 1964. She remembers that date because it was Seeger himself who announced it that night to the COFO workers during his appearance at Mt Olive.

Nineteen men, many of whom were from Meridian, were arrested and charged with the killings, but state charges were soon dropped. The federal government prosecuted them for violation of Schwerner’s, Goodman’s and Chaney’s civil rights, and seven were sentenced to varying terms up to ten years. It took until 2005 for one of the defendants, Edgar Ray Killen, to be brought to justice in a Mississippi court. He was convicted of manslaughter in Neshoba County Circuit Court.

Long before the legal proceedings, though, the families had to bury the dead as a prologue to getting on with their shattered lives. Schwerner and Goodman were taken back to their homes far away in New York.

Chaney’s funeral was held in Meridian. Mourners included his collegues, the COFO workers. The funeral services took place at four different churches, culminating at First Union Baptist Church on 36th Avenue.

As for Freedom Summer, the results were mixed. Some voter registration was accomplished in the face of resistance. People were beaten and killed. Churches were burned. Violence across Mississippi escalated. By any of those measures, it was at least a borderline failure. But the deaths of Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney galvanized public opinion. The 1,000 or so COFO workers returned home from Mississippi with eyewitness testimony about the severity of the situation, many of them with scars to corroborate their stories. The nation realized that the full weight of the law and the federal government would be needed to end the systemic injustice that fostered violence and hatred and shielded murderers. The political pressure became irresistable, and the 1964 Civil Rights Act passed Congress and was promptly signed into law by President Johnson.

Freedom Summer was not the end of apartheid in Mississippi, but it did help deal it a mortal blow.

___________________________________

Thanks to Dr. Bill Scaggs for the info about Pete Seeger, Mark Levy and the Freedom School.

Patti Miller, the COFO volunteer mentioned above, has a Keeping History Alive site where I found several Freedom School photos.

THE SOUND AND THE FURY OF THE UNVANQUISHED POSTMAN

January 1, 2011 § 1 Comment

In December 1924, a postal inspector from Corinth, Miss., leveled a series of charges against the postmaster at the University of Mississippi. “You mistreat mail of all classes,” he wrote, “including registered mail; … you have thrown mail with return postage guaranteed and all other classes into the garbage can by the side entrance,” and “some patrons have gone to this garbage can to get their magazines.”

In December 1924, a postal inspector from Corinth, Miss., leveled a series of charges against the postmaster at the University of Mississippi. “You mistreat mail of all classes,” he wrote, “including registered mail; … you have thrown mail with return postage guaranteed and all other classes into the garbage can by the side entrance,” and “some patrons have gone to this garbage can to get their magazines.”

The slothful postmaster was William Faulkner. He had accepted the position in 1921 while trying to establish himself as a writer, but he spent most of his time in the back of the office, as far as possible from the service windows, in what he called the “reading room.” When he wasn’t reading or writing there he was playing bridge with friends; he would rise grumpily only when a patron rapped on the glass with a coin.

It was a brief career. Shortly after the inspector’s complaint, Faulkner wrote to the postmaster general: “As long as I live under the capitalistic system, I expect to have my life influenced by the demands of moneyed people. But I will be damned if I propose to be at the beck and call of every itinerant scoundrel who has two cents to invest in a postage stamp. This, sir, is my resignation.”

Thanks to Futility Closet.

EVER IS A LITTLE OVER A DOZEN YEARS

September 12, 2010 § Leave a comment

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

It was his children’s inquiries about their father’s childhood that led Eubanks to begin to explore the history of the dark era of his childhood. In his quest for a way to help them understand the complex contradictions of that era, he came across the files of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission and found his parents’ names among those who had been investigated, and he became intrigued to learn more about the state that had spied on its own citizens.

Eubanks’ search led him to Jackson, where he viewed the actual files and their contents and explored the scope of the commission’s activities. He had decided to write a book on the subject, and his research would require trips to Mississippi. It was on these trips that he renewed his acquaintance with the idyllic rural setting of his childhood and the small town of Mount Olive, where, in the middle of his eighth-grade school year, integration came to his school.

There are three remarkable encounters in the book. The author’s meetings with a surviving member of the Sovereignty Commission, a former klansman, and with Ed King, a white Methodist minister who was active in the civil rights movement, are fascinating reading.

The satisfying dénouement of the book is Eubanks’ journey to Mississippi with his two young sons in which he finds reconciliation with his home state and its hostile past.

If there is a flaw in this book, it is a lack of focus and detail. The focus shifts dizzyingly from the Sovereignty Commission, to his relationship with his parents, to his rural boyhood, to life in segregation, to his own children, to his problematic and ultimately healed relatiosnhip with Mississippi. Any one or two of these themes would have been meat enough for one work. As for detail, the reader is left wishing there were more. Eubanks points out that his own experience of segregation was muted because he lived a sheltered country existence, and his memories of integrated schooling are a blur. For such a gifted writer whose pen commands the reader’s attention, it is hard to understand why he did not take a less personal approach and expand the recollections of that era perhaps to include those of his sisters, or other African-Americans contemporaries, or even the white friends he had.

This is an entertaining and thought-provoking book, even with its drawbacks. I would recommend it for anyone who is exploring Mississippi’s metamorphosis from apartheid to open society.

The title of this book has its own interesting history. In June of 1957, Mississippi Governor J. P. Coleman appeared on MEET THE PRESS. He was asked if the public schools in Mississippi would ever be integrated. “Well, ever is a long time,” he replied, ” [but] I would say that a baby born in Mississippi today will never live long enough to see an integrated school.”

In January of 1970, only twelve-and-a-half years after the “ever is a long time” statement, Mississippi public schools were finally integrated by order of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, a member of which, ironically, was Justice J. P. Coleman, former governor of Mississippi.

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WAR

August 28, 2010 § 2 Comments

Through the spring and summer most of my reading has been books dealing with the South in general and Mississippi in particular in the last half of the twentieth century, the era of the struggle for civil rights I still have a few more to read on the topic before I move on to other interests.

One of the seminal events of the civil rights era was the admission of James Meredith as a student at the University of Mississippi in 1962. The confrontation at Ole Miss between the determined Meredith, backed by the power of the federal government, and Mississippi’s segregationist state government culminated in a bloody battle that resulted in two deaths and a shattering blow to the strategies of “massive resistance,” “interposition,” and “states rights” that had been employed to stymie the rights of black citizens in our state.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Lambert, who is a professor of history at Purdue University, not only was a student at Ole Miss in 1962 and an eye-witness to many of the events, he was also a member of the undefeated football team at the time, and his recollection of the chilling address delivered by Governor Ross Barnett at the half-time of the Ole Miss-Kentucky football game on the eve of the battle is a must-read.

This is a small book, only 193 pages including footnotes and index, but it is meticulously researched. As a native Mississippian and eyewitness, Lambert is able not only to relate the historical events, he also is able to describe the context in which they happened.

The book lays out the social milieu that led to the ultimate confrontation. There is a chapter on Growing Up Black in Mississippi, as well as Growing up White in Mississippi. Lambert describes how the black veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict had experienced cultures where they were not repressed because of their race, and they made up their minds that they would challenge American apartheid when they returned home. Meredith was one of those veterans, and he set his sights on attending no less than the state’s flagship university because, as he saw it, a degree from Ole Miss was the key to achievement in the larger society. He also realized that if he could breach the ramparts at Ole Miss, so much more would come tumbling down.

The barriers put up against Meredith because of his race were formidable. He was aware of the case of Clyde Kennard, another black veteran who had tried to enroll at what is now the University of Southern Mississippi, but was framed with trumped-up charges of stolen fertilizer and sentenced to Parchman, eventually dying at age 36. And surely he knew of Clennon King, another black who had managed to enroll at Ole Miss only to be committed to a mental institution for his trouble. Even among civil rights leadrs, Meredith met resistance. He was discouraged by Medgar and Charles Evers, who were designing their own strategy to desegregate Ole Miss, and felt that Meridith did not have the mettle to pull it off. Against all of these obstacles, and in defiance of a society intent on destroying him, Meredith pushed and strove until at last he triumphed.

But his triumph was not without cost. Armed racists from throughout Mississippi, Alabama and other parts of the South streamed to Oxford in response Barnett’s rallying cry for resistance. The governor’s public rabble-rousing was cynically at odds with his private negotiations with President John Kennedy and US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, with whom he sought to negotiate a face-saving way out. The ensuing battle claimed two lives, injured 160 national guardsmen and US marshals, resulted in great property damage, sullied the reputation of the university, tarred the State of Mississippi in the eyes of the world, led to armed occupation of Lafayette County by more than 10,000 federal troops, and forever doomed segregation. Ironically, the cataclysmic confrontation that Barnett and his ilk intended to be the decisive battle that would turn back the tide of civil rights was instead the catalyst by which Ole Miss became Mississippi’s first integrated state university. It was in essence the final battle of the Civil War, the coup de grace to much of what had motivated that conflict in the first place and had never been finally resolved.

As for Meredith, the personal cost to him was enormous. He was subjected to taunts and derision, as well as daily threats of violence and even death. He found himself isolated on campus, and did not even have a roommate until the year he graduated, when the second black student, Cleveland Donald, was admitted. Meredith described himself in 1963 as “The most segregated Negro in the world.”

The admission of James Meredith to Ole Miss not only opened the doors of Mississippi’s universities to blacks, it also helped begin the process in which Mississippians of both races had to confront and come to terms with each other as the barriers fell one by one. As former mayor Richard Howorth of Oxford recently told a reporter: ” … other Americans have the luxury of a sense of security that Mississippi is so much worse than their community. That gives them a sense of adequacy about their racial views and deprives them of the opportunity we’ve had to confront these issues and genuinely understand our history.”

Meredith’s legacy is perhaps best summed up in the fact that, forty years after his struggle, his own son graduated from the University of Mississippi as the Outstanding Doctoral Student in the School of Business, an event that Meredith said, ” … vindicates my entire life.” His son’s achievement is the culmination of Meredith’s singular sacrifice. What Meredith accomplished for his son has accrued to the benefit of blacks and whites alike in Mississippi, and has helped our state begin to unshackle itself from its slavery to racism.

BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA’S MUSIC

August 18, 2010 § Leave a comment

What do all these professional Mississippi musicians have in common?

John Alexander, Metropolitan Opera star Steve Forbert, singer songwriter George Atwood, bass player for Buddy Holly Ty Herndon, country singer Paul Overstreet, country singer songwriter Julian Patrick, Broadway and Metropolitan Opera singer Moe Bandy, country music singer songwriter Eddie Houiston, southern soul singer Don Poythress, country and gospel singer songwriter Clay Barnes, guitarist for Steve Forbert and Willie Nile, session artist for the Who Bobby Jay, rock and roll, soul and R & B musician Carey Bell, blues harmonica player for Muddy Waters Duke Jericho, blues organist for BB King David Ruffin, member of the Temptations Cleo Brown, blues, boogie and jazz pianist and vocalist Sherman Johnson radio show host and juke joint owner Pat Brown, southern soul R & B singer John Kennedy, country bmusic songwriter Jimmy Ruffin, R & B and soul singer, recorded “What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted?” Mike Compton, bluegrass mandolin player featured on soundtrack of “O, Brother, Where Art Thou?” Cap King, blues musician Patrick Sansone, guitarist for Wilco and Autumn Defense George Soulé, singer songwriter Lovie Lee, blues singer George Cummings, composer, guitarist Paul Davis, singer songwriter Scott McQuaig, country music singer songwriter Brain Stephens, drummer Chris Ethridge bass guitarist for Flying Burrito Brothers, Willie Nelson and International Submarine Band Elsie McWilliams, songwriter, Country Music Hall of Fame Ernest Stewart, blues singer Patrice Moncell, blues, soul, jazz and gospel vocalist Dudley Tardo, drummer for the House Rockers, featured in the movie “Last of the Mississippi Jukes” Rosser Emerson, blues musician Steve Moore, country and rock guitarist Cooney Vaughn, blues pianist William Butler Fielder, jazz trumpeter and professor of music at Rutgers University Theresa Needham, Chicago blues club owner Hayley Williams, lead singer for Paramore Alvin Fielder, jazz drummer Duke Otis, band leader Al Wilson, soul singer and drummer Jimmie Rodgers, father of country music, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Country Music Hall of Fame, Songwriters Hall of FameIf you haven’t figured it out by now … every one of them is from Meridian. And Meridian is not unique in our state. Mississippi’s musical legacy is phenomenal.

OLD TIMES HERE ARE NOT FORGOTTEN

August 13, 2010 § 2 Comments

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” — William Faulkner in REQUIEM FOR A NUN

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” — L.P. Hartley in THE GO-BETWEEN

No region of our nation has revered, understood, embraced, been bedevilled by and romanticized its past more than has the South. Much of the South’s history since the Civil War has been the history of evolving race relations in a culture determined to preserve inviolate its notion of its past. Beginning in the 1950’s, however, the irresistable force of change in the form of the civil rights movement collided head-on with the immovable object in the form of “massive resistance,” and the resulting explosion that destroyed the foundation of segregation began the transformation of southern culture that continues to this day.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

On its face, DIXIE is a history of the South’s agonizing journey through the watershed era of the civil rights movement and into the present, a chronicle of the events that shook and shattered our region and sent shock waves across the nation. The events and figures parade across his pages in a comprehensive panorama: The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Meredith and the riot at Ole Miss, Ross Barnett, Jimmy Carter, Eudora Welty, Brown v. Board of Education, Freedom Summer, Aaron Henry, the Ku Klux Klan, the struggle for control of the Democratic Party in Mississippi, White Citizens Councils, sit-ins, John Bell Williams, William Winter, Willie Morris, Charles Evers, Byron de la Beckwith and Sam Bowers, Trent Lott and Thad Cochran, William Waller, the riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968, and more. As a history of the time and how the South tore itself out of the crippling grip of the past, the book is a success.

The great charm and charisma of this book, however, is in the way that Wilkie weaves his own, personal history through the larger events, revealing for the reader how it was to be a southerner in those days, both as an average bystander and as an active participant.

The author grew up in Mississippi, hopscotching around the state until his mother lighted in the town of Summit. His recollection of life in the late 40’s and 50’s in small-town Mississippi echoes the experiences of many of us who were children in those years, and will enlighten those who came along much later.

Wilkie was a freshman at Ole Miss when James Meredith enrolled there in 1962, sparking the riot that ironically spurred passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. On graduation Wilkie took a job with the Clarksdale newspaper and developed many contacts in Mississippi politics that eventually led him to be a delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, where he was an eyewitness to the calamitous events there.

Through a succession of jobs, Wilkie wound up a national and middle-eastern corresondent for the BOSTON GLOBE, and even a White House Correspondent during the Carter years. His observations and first-hand accounts of his personal dealings with many of the leading figures of history through the 60’s and 70’s are fascinating.

When he had left the South, Wilkie believed he was leaving behind a tortured land where change could never take place, and where he could never feel at home with his anti-racism views and belief in racial reconciliation. He saw himself as a romantic exile, a quasi-tragic figure who could never go home again, but over time he found the northeast lacking, and he found the South tugging at him whenever he returned on assignment.

When his mother became ill, Wilkie persuaded his editor to allow him to return south, and he moved to New Orleans, from where he covered the de la Beckwith and Bowers Klan murder trials and renewed his acquaintanceship with many Mississippi political and cultural figures, including Willie Morris, Eudora Welty and William Winter. He began to discover that the south had undergone a sea change in the years that he was away, and that the murderous, hard edge of racism and bigotry had been banished to the shadowy edges, replaced largely by people of good will trying their best to find a way to live together harmoniously. He found a people no longer dominated by the ghosts of the ante-bellum South.

In the final chapter of the book, Wilkie is called home for the funeral of Willie Morris, and the realization arises that he is where he needs to be — at home in the South. His eloquent end-note answered a question Morris had posed to him some years before: “Curtis, can you tell us why you came home?” Wilkie’s response:

Just as Vernon Dahmer, Jr. had said, I, too believe I came home to be with my people. We are a different people, with our odd customs and manner of speaking and our stubborn, stubborn pride. Perhaps we are no kinder than others, but it seems to me we are … We appreciate our history and recognize our flaws much better than our critics. And like our great river, which overcomes impediments by creating fresh channels, we have been able in the span of Willie’s lifetime and my own to adjust our course. Some think us benighted and accursed, but I like to believe the South is blessed with basic goodness. Even though I was angry with the South and gone for years, I never forsook my heritage. Eventually, I discovered that I had always loved the place. Yes, Willie, I came home to be with my people.

Those of you who lived through the troubled years recounted here will find that Wilkie’s accounts bring back memories that are sometimes painful and sometimes sweet. For readers who are too young to recall that era, this book is an excellent history as well as an eye-opening account of what it was like to grow up in that South.

Wilkie’s new book, THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS, about the Scruggs judicial bribery scandal, is due out in October.