EVER IS A LITTLE OVER A DOZEN YEARS

September 12, 2010 § Leave a comment

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

W. Ralph Eubanks is publishing editor at the Library of Congress and a native of Covington County, Mississippi. His book, EVER IS A LONG TIME, is a thought-provoking exploration of Mississippi in the 1960’s, 70’s, and the present, from the perspective of a black child who grew up in segregation and experienced integration, and that of a young black man who earned a degree from Ole Miss, left Mississippi vowing never to return, achieved in his profession, established a family, and eventually found a way to reconcile himself to the land of his birth.

It was his children’s inquiries about their father’s childhood that led Eubanks to begin to explore the history of the dark era of his childhood. In his quest for a way to help them understand the complex contradictions of that era, he came across the files of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission and found his parents’ names among those who had been investigated, and he became intrigued to learn more about the state that had spied on its own citizens.

Eubanks’ search led him to Jackson, where he viewed the actual files and their contents and explored the scope of the commission’s activities. He had decided to write a book on the subject, and his research would require trips to Mississippi. It was on these trips that he renewed his acquaintance with the idyllic rural setting of his childhood and the small town of Mount Olive, where, in the middle of his eighth-grade school year, integration came to his school.

There are three remarkable encounters in the book. The author’s meetings with a surviving member of the Sovereignty Commission, a former klansman, and with Ed King, a white Methodist minister who was active in the civil rights movement, are fascinating reading.

The satisfying dénouement of the book is Eubanks’ journey to Mississippi with his two young sons in which he finds reconciliation with his home state and its hostile past.

If there is a flaw in this book, it is a lack of focus and detail. The focus shifts dizzyingly from the Sovereignty Commission, to his relationship with his parents, to his rural boyhood, to life in segregation, to his own children, to his problematic and ultimately healed relatiosnhip with Mississippi. Any one or two of these themes would have been meat enough for one work. As for detail, the reader is left wishing there were more. Eubanks points out that his own experience of segregation was muted because he lived a sheltered country existence, and his memories of integrated schooling are a blur. For such a gifted writer whose pen commands the reader’s attention, it is hard to understand why he did not take a less personal approach and expand the recollections of that era perhaps to include those of his sisters, or other African-Americans contemporaries, or even the white friends he had.

This is an entertaining and thought-provoking book, even with its drawbacks. I would recommend it for anyone who is exploring Mississippi’s metamorphosis from apartheid to open society.

The title of this book has its own interesting history. In June of 1957, Mississippi Governor J. P. Coleman appeared on MEET THE PRESS. He was asked if the public schools in Mississippi would ever be integrated. “Well, ever is a long time,” he replied, ” [but] I would say that a baby born in Mississippi today will never live long enough to see an integrated school.”

In January of 1970, only twelve-and-a-half years after the “ever is a long time” statement, Mississippi public schools were finally integrated by order of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, a member of which, ironically, was Justice J. P. Coleman, former governor of Mississippi.

CHANCERY COURT IN DAYS OF YORE, PART DEUX

September 10, 2010 § 2 Comments

[Chancery Court in Days of Yore, Part One and “High Waters” and Burlap Suits are two older posts that touch on some of these same themes]

Recently in a ramble through the Uniform Chancery Court Rules (UCCR) I stumbled on a couple of curious throwbacks to pre-MRCP practice. You can read and scratch your head over these historical anomalies in Chapter 2 of the rules, dealing with pleadings. I won’t repeat them here, but they include references to bills of complaint, cross-bills and demurrers, as in “Trial not Delayed Because Demurrer Overruled.”

The references to those ancient and outmoded engines of the law got me thinking about that pre-MRCP era when the practice of law was, well, quainter than it is today. So travel back in time with me to 1979, when the “new rules” were not even yet a rumor, being two years away from adoption and four years from going into effect. Things were different then. Or maybe they were really the same, in a different way.

In 1979, Judge Neville ruled his courtroom like a Teutonic prince. He was sovereign, dictator, despot and all-wise, solomonic adjudicator. There were no “factors” for the Chancellor to consider. The Supreme Court understood the role of the Chancellor as finder of fact in complex human relationships and respected him as such. That was back in the day when most appellate judges had trial court experience, including Chancery experience, and the Court of Appeals had not yet been invented.

It’s trial day in a divorce you filed for a friend’s sister. Counsel opposite, a grizzled veteran, has filed a demurrer attacking your Bill of Complaint for Divorce, and the demurrer will be taken up in chambers before the trial. Whether the demurrer is granted in whole or in part, the trial will follow as night follows day because, “Trial not Delayed Because Demurrer Overruled.” The judge could grant a postponement if your case is gutted by the demurrer, but you know Judge Neville isn’t likely to do so, and your client wants this over with anyway.

You settle your client into the courtroom (now Judge Mason’s courtroom) for the duration. You’ve already explained to her that the judge may strike out part of the pleadings you filed on her behalf, but that you’re confident everything will be fine. That’s what you told her, not what you really feel. What you really feel is a knot in your stomach the size of Mount Rushmore.

You gather your file and leave your client in the dark-panelled court room, where dour portraits of previous Chancellors who practiced their alchemy in that chamber, their medieval visages glowering down disdainfully as if they sniff disagreeably the fetid aroma of the weaknesses in your case, stare balefully down on your misery.

In Judge Neville’s dim chambers (Cindy James’ office today), you wait while he relieves himself in the facilities. The air is redolent with fragrance of his ever-present pipe. There are wisps of smoke clinging to the ceiling like disembodied spirits. On the dark-panelled wall is a plaque that reads:

“If you are well, you have nothing to worry about; If you are sick, you have two things to worry about: whether you will live or whether you will die; If you live you have nothing to worry about; If ou die, you have only two things to worry about: whether you will go to heaven or whether you will go to hell; If you go to heaven you have nothing to worry about; If you go to hell, you’ll be so busy greeting your old friends that you won’t have time to worry!”

Before long, your older and more experienced opponent, wielding his superior knowledge of the byzantine rules of pleading, has prevailed, and the negative pregnants and other flaws in your pleading have been lopped away like infected warts. Before you know it, the 36-page Bill of Complaint for Divorce that you proudly filed has been whittled town to a dozen miserable pages.

Before turning you loose for the court room, the judge takes the opportunity to use his best cajolery skills to try to settle the case, telling you how he would rule on this issue and that, and even cussing you good for wasting the court’s precious time. He runs his hand over his balding head, adjusts his glasses, and you can see the trademark red flush spreading up his cheeks toward his forehead, but you stand your ground because you’ve already tried to no avail to talk your clint into a reasonable settlement.

You emerge into the comparatively brightly-lit court room and flash a brave smile at your client. Her attempt at looking brave looks more like crestfallen to you.

The floor is cork, scarred from years of cigarette burns. Brass spitoons, polished and emptied weekly by a jail trusty, are set on each side of the court room, one for the complainant and one for the defendant. In a corner plainly visible to the lawyers is a Coca-Cola clock; the art deco clock built into another wall stopped years ago at 10:05.

In the court room, the old lawyer has taken his place. He is chain smoking cigarettes. As he finishes one, he drops it on the floor and grinds it out under the sole of his two-tone wing-tips on the cork floor. He lights another and removes his linen jacket, revealing his short-sleeve shirt. He is wearing a cheap clip-on tie with Weidmann’s soup stains. His polyester slacks are held up by suspenders. His greased head gleams in the court room light. He is no fashion plate, but he is a dangerous adversary who only a few minutes ago gutted your case. He will smoke like that through the trial, his jacket hanging limply on his chair as he carves up your witnesses.

Your office file has only a few papers in it. There is no voluminous discovery, because you don’t get to propound interrogatories and requests for production. The only discovery is to ask for a Bill of Particulars. The rules of pleading are so arcane and complex that a misplaced adjective just might doom an essential element of your case. The older lawyers have mastered the strange warcraft of pleading and gleefully ambush you from the legal thickets, catching you unawares and pillaging the smoking ruins of your lawsuit.

As the older lawyer tends to other preparatory business, he lays his cigarette on the edge of the table, and the burning end inflicts yet another scar into counsel’s table, adding one more to the many other burn marks. He sticks the cigarette back into his mouth and approaches you to show you some document, wreathing your face in a fog of smoke and raining ashes on the natty pin-striped suit you bought from Harry Mayer (the elder) only last week.

Judge Neville takes the bench, his smoking pipe emitting inscrutable signals, clad in his customary dark suit. Chancellors did not wear a black robe back then, but he is wearing his black suit today, probably in mourning for my case, you muse. Your voice quavers as you read your pleadings into the record for the court, followed by the older lawyer. While you are struggling through the reading, Judge Neville is puffing pensively on his pipe and whittling strenuously on a cedar plug. Shavings curl slowly at first, and then furiously, as the pleadings pour from your mouth into the record for God and all the world to hear, the flaws and weaknesses drawing into clear focus with every heretofore and to-wit, and your spirits sag at the prospect of sour defeat.

By agreement the grounds for divorce are presented first, and the judge will rule whether a divorce will be granted. You call the opposing party first and he denies everything. Your client then testifies unconvincingly about her husband’s mistreatment. Her performance on cross is frightful. The corroborating witness might as well have been in Peru when the offending conduct is alleged to have occurred. Judge Neville ponders and whittles, maufacturing acrid clouds from his pipe. Tension builds until the judge intones his opinion that, “The grounds for divorce are not strong, but the court finds that these parties need to be divorced, and so I will grant the Complainant a divorce.” Whew. It was fairly common for Chancellors to do that back then, but it’s still a relief to get over that hump.

You rise to call your first witness on the remaining issues, but Judge Neville interrupts you in his stentorian tone, “Suh, I will see the lawyuhs in chambuhs,” and he leaps to his feet and bounds out of the court room and into his office, his pipe jutting decisively out of his face. You know what is coming. It’s the arm-twisting conference where the Judge, now that he’s granted the divorce, will bring all of his considerable persuasive power and intimidation to bear. In chambers he wheedles, threatens, sweet-talks, cajoles, cusses and pounds his desk, demanding that you settle, or else.

You confer with your client who is now more amenable to a settlement, having been tenderized by opposing counsel. A few more sessions with the Chancellor and the case is settled.

Somehow you paint the best face on your performance for your client. She’s not thrilled with the settlement, but it’s not really bad for those days: She gets her divorce and custody of the baby; her ex-husband will have to pay a respectable $35 a week for child support (her best friend got a divorce last month and got only $60 a month; after all, there were no statutory child support guidelines then); her ex gets the house because it is titled only in his name (no equitable distribution then; title controlled); she gets the 1971 Dodge, and he will pay the $65 monthly note; she will have to pay the $120 McRae’s bill; she will get the living room and bedroom suites, baby furniture and the 19-inch RCA black-and-white television, and he will get the 19-inch Westinghouse color tv. She’s not terribly happy, but all in all, she’s fairly satisfied that she got good value for the $250 that she paid you to handle her contested divorce.

In the clerk’s office, you stop to visit with Mr. M.B. Cobb, the gentlemanly Chancery Clerk, and deputy clerk Joyce Smith, who try to console you about your misfire in court. That new young deputy clerk, Rubye Hayes, is disgruntled about something, so you try not to lay your already-bruised ego in her path.

Leaving the court house, you meander over to the Southern Kitchen where you find the company of jovial lawyers and even your older adversary scarfing down coffee and pie, as they do every day. You pull up a chair and order a comforting slice of lemon icebox pie, and before your first forkful, you are the butt of their ribbing about how you folded your hot hand when Neville called your bluff. You fight not to blush, but you can’t help but smile with the satisfaction of knowing that they only treat colleagues that way, and that much of their humor is part painful experience and part shared pain.

It’s nearly 10:30, and you head back to your office. You wonder whether you’ll get to finish reading that new John D. MacDonald detective novel or whether you’ll have some work to do.

Back at the office, you have two new clients awaiting, and you receipt them and open files in time for lunch. But before leaving, you ask your secretary to type up the pleadings, which will be on legal-sized paper, the original on bond, and the several copies made with carbon paper on onion-skin; you can’t yet afford the latest technological advance: an IBM memory typewriter. Word processors and computers are unknown. You prefer carbons to photocopies (all of which were called “xerox copies” back then) because your copier, like most, makes sepia-colored copies on slick, coated paper from a roll in the machine, and the copies are not favored by the judges because they tend to curl up and are hard to handle, but worst of all, they tend to turn dark or black over time and become illegible.

Ordinarily you would head over to Weidmann’s to sit at the lunch counter over a vegetable plate with cracklin bread and see many of the people you know, or to the Orange Bowl for a cheeseburger, but today you’ve decided to recover from your court room wounds by spending the afternoon on a friend’s lake, casting crickets on a quill with a fly rod for chinkapins and having a few cool ones. You stop at the bait shop next to Anderson Hospital and visit with James Elmer Smith while he scoops up your crickets. One great thing about being out on the lake: no one will bother you there because there were no cell phones then; in fact, many people still had dial telephones.

On your way out to the lake you think to yourself what a good life you have and how even a disappointing day in court is not so bad in the whole flow of things. And tomorrow is a whole, new day.

FIVE YEARS AFTER

August 29, 2010 § Leave a comment

It was five years ago today — August 29, 2005 — that Hurricane Katrina brought death and devastation to New Orleans, the Mississippi Gulf Coast and south-central Mississippi.

The news this weekend cast the familiar images of flooded homes in the Lower Ninth Ward, Bay St. Louis reduced to piles of debris, the Superdome, victims clamoring for help, and on and on.

The storm was still powerful when it crossed east Mississippi near Newton, bringing 85-mile-per-hour winds with gusts to 105 here in Meridian. More than one thousand homes in Meridian suffered serious damage. It took nearly two weeks to restore electric service throughout the city and county, and the damage to structures took years to repair. The devastation was astonishing considering that Meridian is nearly 200 miles inland.

In the years since Katrina the Mississippi Gulf Coast has rebounded well. Rebuilding is a continuing process, and there are ongoing battles between property owners and insurers, but the resilience of the Coast makes all Mississippians proud.

New Orleans, on the other hand, has struggled. The dysfunctional near-anarchy of the Big Easy that has always been one of its most endearing features as an entertainment center has not served it well in its efforts to recover. The city’s population is significantly reduced (the poverty-plagued Lower Ninth Ward had 18,000 residents before the storm and now has around 1,800), and many damaged neighborhoods, particularly in the east, remain mostly boarded up and abandoned. There are still 50,000 abandoned homes in the city. Convention business and tourism, the lifeblood of the city, are greatly diminished. New Orleans is down, for sure, but not out. New Orleans is now the fastest-growing city in the US. The New York Times has an interesting article, with video, showing evolution of two streets near the Industrial Canal in the Lower Ninth both before and since Katrina [Thanks to nmisscommentor for letting us know about it]. There is a University of Southern California study of damage in the area, with video, here.

New Orleans, on the other hand, has struggled. The dysfunctional near-anarchy of the Big Easy that has always been one of its most endearing features as an entertainment center has not served it well in its efforts to recover. The city’s population is significantly reduced (the poverty-plagued Lower Ninth Ward had 18,000 residents before the storm and now has around 1,800), and many damaged neighborhoods, particularly in the east, remain mostly boarded up and abandoned. There are still 50,000 abandoned homes in the city. Convention business and tourism, the lifeblood of the city, are greatly diminished. New Orleans is down, for sure, but not out. New Orleans is now the fastest-growing city in the US. The New York Times has an interesting article, with video, showing evolution of two streets near the Industrial Canal in the Lower Ninth both before and since Katrina [Thanks to nmisscommentor for letting us know about it]. There is a University of Southern California study of damage in the area, with video, here.

Today, three tropical cylones are churning across the Atlantic, with yet another tropical wave trailing them out of Africa. Is our next Katrina among them? We pray not.

THE LAST BATTLE OF THE CIVIL WAR

August 28, 2010 § 2 Comments

Through the spring and summer most of my reading has been books dealing with the South in general and Mississippi in particular in the last half of the twentieth century, the era of the struggle for civil rights I still have a few more to read on the topic before I move on to other interests.

One of the seminal events of the civil rights era was the admission of James Meredith as a student at the University of Mississippi in 1962. The confrontation at Ole Miss between the determined Meredith, backed by the power of the federal government, and Mississippi’s segregationist state government culminated in a bloody battle that resulted in two deaths and a shattering blow to the strategies of “massive resistance,” “interposition,” and “states rights” that had been employed to stymie the rights of black citizens in our state.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Frank Lambert has authored a gem of a book in THE BATTLE OF OLE MISS: Civil Rights v. States Rights, published this year by the Oxford University Press. If you have any interest in reading about that that troublesome time, you should make this book a starting point.

Lambert, who is a professor of history at Purdue University, not only was a student at Ole Miss in 1962 and an eye-witness to many of the events, he was also a member of the undefeated football team at the time, and his recollection of the chilling address delivered by Governor Ross Barnett at the half-time of the Ole Miss-Kentucky football game on the eve of the battle is a must-read.

This is a small book, only 193 pages including footnotes and index, but it is meticulously researched. As a native Mississippian and eyewitness, Lambert is able not only to relate the historical events, he also is able to describe the context in which they happened.

The book lays out the social milieu that led to the ultimate confrontation. There is a chapter on Growing Up Black in Mississippi, as well as Growing up White in Mississippi. Lambert describes how the black veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict had experienced cultures where they were not repressed because of their race, and they made up their minds that they would challenge American apartheid when they returned home. Meredith was one of those veterans, and he set his sights on attending no less than the state’s flagship university because, as he saw it, a degree from Ole Miss was the key to achievement in the larger society. He also realized that if he could breach the ramparts at Ole Miss, so much more would come tumbling down.

The barriers put up against Meredith because of his race were formidable. He was aware of the case of Clyde Kennard, another black veteran who had tried to enroll at what is now the University of Southern Mississippi, but was framed with trumped-up charges of stolen fertilizer and sentenced to Parchman, eventually dying at age 36. And surely he knew of Clennon King, another black who had managed to enroll at Ole Miss only to be committed to a mental institution for his trouble. Even among civil rights leadrs, Meredith met resistance. He was discouraged by Medgar and Charles Evers, who were designing their own strategy to desegregate Ole Miss, and felt that Meridith did not have the mettle to pull it off. Against all of these obstacles, and in defiance of a society intent on destroying him, Meredith pushed and strove until at last he triumphed.

But his triumph was not without cost. Armed racists from throughout Mississippi, Alabama and other parts of the South streamed to Oxford in response Barnett’s rallying cry for resistance. The governor’s public rabble-rousing was cynically at odds with his private negotiations with President John Kennedy and US Attorney General Bobby Kennedy, with whom he sought to negotiate a face-saving way out. The ensuing battle claimed two lives, injured 160 national guardsmen and US marshals, resulted in great property damage, sullied the reputation of the university, tarred the State of Mississippi in the eyes of the world, led to armed occupation of Lafayette County by more than 10,000 federal troops, and forever doomed segregation. Ironically, the cataclysmic confrontation that Barnett and his ilk intended to be the decisive battle that would turn back the tide of civil rights was instead the catalyst by which Ole Miss became Mississippi’s first integrated state university. It was in essence the final battle of the Civil War, the coup de grace to much of what had motivated that conflict in the first place and had never been finally resolved.

As for Meredith, the personal cost to him was enormous. He was subjected to taunts and derision, as well as daily threats of violence and even death. He found himself isolated on campus, and did not even have a roommate until the year he graduated, when the second black student, Cleveland Donald, was admitted. Meredith described himself in 1963 as “The most segregated Negro in the world.”

The admission of James Meredith to Ole Miss not only opened the doors of Mississippi’s universities to blacks, it also helped begin the process in which Mississippians of both races had to confront and come to terms with each other as the barriers fell one by one. As former mayor Richard Howorth of Oxford recently told a reporter: ” … other Americans have the luxury of a sense of security that Mississippi is so much worse than their community. That gives them a sense of adequacy about their racial views and deprives them of the opportunity we’ve had to confront these issues and genuinely understand our history.”

Meredith’s legacy is perhaps best summed up in the fact that, forty years after his struggle, his own son graduated from the University of Mississippi as the Outstanding Doctoral Student in the School of Business, an event that Meredith said, ” … vindicates my entire life.” His son’s achievement is the culmination of Meredith’s singular sacrifice. What Meredith accomplished for his son has accrued to the benefit of blacks and whites alike in Mississippi, and has helped our state begin to unshackle itself from its slavery to racism.

ANSWERS TO WICKED MISSISSIPPI TRIVIA

August 20, 2010 § Leave a comment

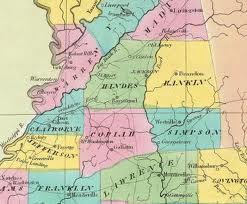

1. Which Mississippi county changed its name in 1865 to Davis County in honor of Jefferson Davis and the name of its county seat to Leesburg, in honor of Robert E. Lee? What was the name of the original county seat? (Note: the names were restored to their originals in 1869).

It was Jones County. Ellisville was the original county seat, because Laurel, which is now one of the two county seats, was not founded until 1882.

2. What is the present-day name of the Mississippi county that was established in 1871 as Colfax County?

Clay. Colfax County was created in 1871 from parts of Chickasaw, Lowndes, Oktibbeha and Monroe. It changed its name in 1876 to honor Henry Clay.

3. From which present-day county did Bainbridge County separate in1823, only to merge back into its original county in 1824?

Covington. There is no record of the reason for the establishment of Bainbridge county, or for its dissolution, nor is there any identfication of the person or place for whom the county was named in the act establishing it.

4. What is the present-day name of the Mississippi county that was established in 1874 as Sumner County?

Webster. The county was renamed in honor of Daniel Webster in 1882.

5. In 1918 , the last county to be established in Mississippi was formed. What is its name?

Humphreys. Named for Benjamin Humphreys, 26th governor of Mississippi.

6. What present-day county seat was founded in 1832 as the Town of Jefferson? (Note: no relation to the Faulkner’s fictional town of the same name).

Hernando.

7. John L. Sullivan defeated Jake Kilrain in 1889 in the last official bare-knuckled bout in what was then Perry County. In which present-day county is the site located?

Forrest. Forrest County was carved out of the western part of Perry County in 1908.

8. President James K. Polk owned a 1,120-acre estate in the Troy community of which present-day county from 1835-1849?

Grenada.

9. Which Mississippi county seat was the home of thirteen generals of the Confederacy?

Holly Springs. The original name of the town was “Suavatooky,” which would have been a nightmare for today’s image-conscious tourism promoters.

10. Which Mississippi town was named after a newspaper published in another state?

Picayune. Eliza Jane Nicholson, a famed poet and resident of Pearl River County, was editor of the New Orleans Picayune, now the Times-Picayune, and the town was named in honor of her achievements.

11. In which Mississippi county did Teddy Roosevelt’s famous bear hunt take place in 1902 in the community of Smedes?

Sharkey. Smedes was the name of the train landing at Onward Plantation in Sharkey County. Onward, which is the surviving community in the vicinity of the plantation, is usually given as the locale, since the train landing has long since disappeared. You can read the fascinating story how African-American Holt Collier, legendary bear hunter, former slave, Confederate soldier and Texas cowboy, guided Roosevelt on his hunt here.

12. In which Mississippi county does the “Southern cross the Dog?”

Sunflower. At Moorhead, where a line of the Southern Railway crossed the Yazoo and Delta (YD=Yellow Dog, or “Dog”) at a 90-degree angle, reputedly the only place in the western hemisphere where two rail lines cross at a perpindicular. The junction is mentioned in blues recordings, notably by W.C. Handy and Bessie Smith.

13. Which Mississippi county’s name is derived from an Indian name meaning “tadpole place?”

Yalobusha. Some other unusual names: Pontotoc means “weed prairie” or “land of hanging grapes”; Noxubee means “stinking water,” and Oktibbeha means “bloody water”; and Attala was named after the heroine of an 1801 novella by Franois-Rene de Chateaubriand, spelled Atala in his work.

BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA’S MUSIC

August 18, 2010 § Leave a comment

What do all these professional Mississippi musicians have in common?

John Alexander, Metropolitan Opera star Steve Forbert, singer songwriter George Atwood, bass player for Buddy Holly Ty Herndon, country singer Paul Overstreet, country singer songwriter Julian Patrick, Broadway and Metropolitan Opera singer Moe Bandy, country music singer songwriter Eddie Houiston, southern soul singer Don Poythress, country and gospel singer songwriter Clay Barnes, guitarist for Steve Forbert and Willie Nile, session artist for the Who Bobby Jay, rock and roll, soul and R & B musician Carey Bell, blues harmonica player for Muddy Waters Duke Jericho, blues organist for BB King David Ruffin, member of the Temptations Cleo Brown, blues, boogie and jazz pianist and vocalist Sherman Johnson radio show host and juke joint owner Pat Brown, southern soul R & B singer John Kennedy, country bmusic songwriter Jimmy Ruffin, R & B and soul singer, recorded “What Becomes of the Broken-Hearted?” Mike Compton, bluegrass mandolin player featured on soundtrack of “O, Brother, Where Art Thou?” Cap King, blues musician Patrick Sansone, guitarist for Wilco and Autumn Defense George Soulé, singer songwriter Lovie Lee, blues singer George Cummings, composer, guitarist Paul Davis, singer songwriter Scott McQuaig, country music singer songwriter Brain Stephens, drummer Chris Ethridge bass guitarist for Flying Burrito Brothers, Willie Nelson and International Submarine Band Elsie McWilliams, songwriter, Country Music Hall of Fame Ernest Stewart, blues singer Patrice Moncell, blues, soul, jazz and gospel vocalist Dudley Tardo, drummer for the House Rockers, featured in the movie “Last of the Mississippi Jukes” Rosser Emerson, blues musician Steve Moore, country and rock guitarist Cooney Vaughn, blues pianist William Butler Fielder, jazz trumpeter and professor of music at Rutgers University Theresa Needham, Chicago blues club owner Hayley Williams, lead singer for Paramore Alvin Fielder, jazz drummer Duke Otis, band leader Al Wilson, soul singer and drummer Jimmie Rodgers, father of country music, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Country Music Hall of Fame, Songwriters Hall of FameIf you haven’t figured it out by now … every one of them is from Meridian. And Meridian is not unique in our state. Mississippi’s musical legacy is phenomenal.

OLD TIMES HERE ARE NOT FORGOTTEN

August 13, 2010 § 2 Comments

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” — William Faulkner in REQUIEM FOR A NUN

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” — L.P. Hartley in THE GO-BETWEEN

No region of our nation has revered, understood, embraced, been bedevilled by and romanticized its past more than has the South. Much of the South’s history since the Civil War has been the history of evolving race relations in a culture determined to preserve inviolate its notion of its past. Beginning in the 1950’s, however, the irresistable force of change in the form of the civil rights movement collided head-on with the immovable object in the form of “massive resistance,” and the resulting explosion that destroyed the foundation of segregation began the transformation of southern culture that continues to this day.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

Bill May called my attention to DIXIE, by Curtis Wilkie. I had seen this book in various book stores (as I had seen its author, Mr. Wilkie, around Oxford), but had passed it over. On Bill’s recommendation, I got a copy and read it.

On its face, DIXIE is a history of the South’s agonizing journey through the watershed era of the civil rights movement and into the present, a chronicle of the events that shook and shattered our region and sent shock waves across the nation. The events and figures parade across his pages in a comprehensive panorama: The assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., James Meredith and the riot at Ole Miss, Ross Barnett, Jimmy Carter, Eudora Welty, Brown v. Board of Education, Freedom Summer, Aaron Henry, the Ku Klux Klan, the struggle for control of the Democratic Party in Mississippi, White Citizens Councils, sit-ins, John Bell Williams, William Winter, Willie Morris, Charles Evers, Byron de la Beckwith and Sam Bowers, Trent Lott and Thad Cochran, William Waller, the riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968, and more. As a history of the time and how the South tore itself out of the crippling grip of the past, the book is a success.

The great charm and charisma of this book, however, is in the way that Wilkie weaves his own, personal history through the larger events, revealing for the reader how it was to be a southerner in those days, both as an average bystander and as an active participant.

The author grew up in Mississippi, hopscotching around the state until his mother lighted in the town of Summit. His recollection of life in the late 40’s and 50’s in small-town Mississippi echoes the experiences of many of us who were children in those years, and will enlighten those who came along much later.

Wilkie was a freshman at Ole Miss when James Meredith enrolled there in 1962, sparking the riot that ironically spurred passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. On graduation Wilkie took a job with the Clarksdale newspaper and developed many contacts in Mississippi politics that eventually led him to be a delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, where he was an eyewitness to the calamitous events there.

Through a succession of jobs, Wilkie wound up a national and middle-eastern corresondent for the BOSTON GLOBE, and even a White House Correspondent during the Carter years. His observations and first-hand accounts of his personal dealings with many of the leading figures of history through the 60’s and 70’s are fascinating.

When he had left the South, Wilkie believed he was leaving behind a tortured land where change could never take place, and where he could never feel at home with his anti-racism views and belief in racial reconciliation. He saw himself as a romantic exile, a quasi-tragic figure who could never go home again, but over time he found the northeast lacking, and he found the South tugging at him whenever he returned on assignment.

When his mother became ill, Wilkie persuaded his editor to allow him to return south, and he moved to New Orleans, from where he covered the de la Beckwith and Bowers Klan murder trials and renewed his acquaintanceship with many Mississippi political and cultural figures, including Willie Morris, Eudora Welty and William Winter. He began to discover that the south had undergone a sea change in the years that he was away, and that the murderous, hard edge of racism and bigotry had been banished to the shadowy edges, replaced largely by people of good will trying their best to find a way to live together harmoniously. He found a people no longer dominated by the ghosts of the ante-bellum South.

In the final chapter of the book, Wilkie is called home for the funeral of Willie Morris, and the realization arises that he is where he needs to be — at home in the South. His eloquent end-note answered a question Morris had posed to him some years before: “Curtis, can you tell us why you came home?” Wilkie’s response:

Just as Vernon Dahmer, Jr. had said, I, too believe I came home to be with my people. We are a different people, with our odd customs and manner of speaking and our stubborn, stubborn pride. Perhaps we are no kinder than others, but it seems to me we are … We appreciate our history and recognize our flaws much better than our critics. And like our great river, which overcomes impediments by creating fresh channels, we have been able in the span of Willie’s lifetime and my own to adjust our course. Some think us benighted and accursed, but I like to believe the South is blessed with basic goodness. Even though I was angry with the South and gone for years, I never forsook my heritage. Eventually, I discovered that I had always loved the place. Yes, Willie, I came home to be with my people.

Those of you who lived through the troubled years recounted here will find that Wilkie’s accounts bring back memories that are sometimes painful and sometimes sweet. For readers who are too young to recall that era, this book is an excellent history as well as an eye-opening account of what it was like to grow up in that South.

Wilkie’s new book, THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF ZEUS, about the Scruggs judicial bribery scandal, is due out in October.

WICKED MISSISSIPPI TRIVIA

August 11, 2010 § 15 Comments

Answers next week

1. Which Mississippi county changed its name in 1865 to Davis County in honor of Jefferson Davis, and the name of its county seat to Leesburg, in honor of Robert E. Lee? What was the name of the original county seat? (Note: the names were restored to their originals in 1869).

1. Which Mississippi county changed its name in 1865 to Davis County in honor of Jefferson Davis, and the name of its county seat to Leesburg, in honor of Robert E. Lee? What was the name of the original county seat? (Note: the names were restored to their originals in 1869).

2. What is the present-day name of the Mississippi county that was established in 1871 as Colfax County?

3. From which present-day county did Bainbridge County separate in1823, only to merge back into its original county in 1824?

4. What is the present-day name of the Mississippi county that was established in 1874 as Sumner County?

5. In 1918 , the last county to be established in Mississippi was formed. What is its name?

6. What present-day county seat was founded in 1832 as the Town of Jefferson? (Note: no relation to the Faulkner’s fictional town of the same name).

7. John L. Sullivan defeated Jake Kilrain in 1889 in the last official bare-knuckled bout in what was then Perry County. In which present-day county is the site located?

8. President James K. Polk owned a 1,120-acre estate in the Troy community of which present-day county from 1835-1849?

9. Which Mississippi county seat was the home of thirteen generals of the Confederacy?

10. Which Mississippi town was named after a newspaper published in another state?

11. In which Mississippi county did Teddy Roosevelt’s famous bear hunt take place in 1902 in the community of Smedes?

12. In which Mississippi county does the “Southern cross the Dog?”

13. Which Mississippi county’s name is derived from an Indian name meaning “tadpole place?”

LOOKING BACK AT WEIDMANN’S

August 7, 2010 § Leave a comment

A Weidmann’s photo gallery …

Thanks to The World According to Carl for these photos, except for the bottom one, which was taken by my wife. Reminiscences of the original Weidmann’s are at Carl’s website.