JUDGE, JURY … AND INTERROGATOR

February 14, 2012 § 2 Comments

Lawyers frequently refer to the fact that chancellors are “judge and jury” because the chancellor makes findings of fact as well as conclusions of law in the case.

But there’s another legitimate role of the chancellor … developer of the facts. It’s a duty of chancellors long recognized in our jurisprudence, as this passage from the venerable case of Moore v. Sykes’ Estate, 167 Miss. 212, 219-221, 149 So. 789, 791 (1933), illustrates:

“Ever since our chancery court system has been in operation in this state, going back to the earlier days of our judicial history, it has been an established and well-recognized part of that system that one of the important obligations of the chancellor is to see that causes are fully and definitely developed on the facts, and that so far as practicable every issue on the merits shall be covered in testimony, if available, rather than that results may be labored out by inferences, or decisions reached for want of testimony when the testimony at hand discloses that other and pertinent testimony can be had, and which when had will furnish a firmer path upon which to travel towards the justice of the case in hand. The power and obligation reaches back into the ancient days of chancery when the chancellor called the parties before him and conducted a thorough and searching examination of the parties and the available witnesses and decreed accordingly. And, while now this duty of calling the witnesses and the conduct of their examination is placed in the first instance and generally throughout on counsel, the power and duty of the chancellor in that respect is not thereby abrogated; and while to be exercised only in cases in which it is fairly clear that the duty of the chancellor to intervene has arrived and is present, when that situation does arise and is perceived to be present, the duty must be exercised and is as obligatory as any other responsible duty which the constitution of the court imposes on the chancellor.”

And where the attorneys have failed to develop the proof necessary, the chancellor may reopen the proof, or leave the record open to acquire the necessary proof, so as to be able to adjudicate the case. In In re Prine’s Estate, 208 So.2d 187, 192-93 (Miss. 1968), the court said:

“More than a half century ago our Supreme Court in Beard v. Green, 51 Miss. (856) 859, expressly pronounced upon the obligation and responsibility mentioned, and in that case said: ‘The power of the chancery court to remand a cause for further proof at any time before final decree, and in some cases after it, either with or without the consent of parties, is one of the marked characteristics distinguishing it from a court of law, and is one of its most salutary and beneficent powers. It should always be exercised where it is necessary to the ascertainment of the true merits of the controversy.’ And the court went on to say that it was immaterial as to how the necessity of the action by the court arose, whether through inattention or misapprehension or misconception by counsel or litigants, and that none of these or the like should be allowed to prevent the doing of justice. And the duty of the chancellor in this respect was again declared in a later case, McAllister v. Richardson, 103 Miss. (418), 433, 60 So. 570, 572, wherein it was pointed out that the duty, and this of course carries the power, is not only to remand to rules, but includes the obligation on the part of the chancellor during the hearing to see ‘that all proper testimony was introduced to enable him to render a decision giving exact justice between the contending parties’-to conduct the hearing in such manner ‘that all testimony which will throw light upon the matters in controversy is introduced,‘ and that he is within his privileges and duties in aiding to bring out further competent and relevant evidence during the examination of the witnesses who are produced.”

The ancient practice is incorporated in MRE 614, which expressly provides that “The court may, on its own motion or at the suggestion of a party, call witnesses, and all parties are entitled to cross-examine witnesses thus called.” The rule goes on to say that the court may itself interrogate any witness called by anyone, and objections to the court calling or interrogating a witness in chancery should be contemporaneous.

Imagine a case where only one side puts on proof of the Albright factors in a child custody case with horrific allegations. The neglectful side is represented by counsel who is not quite up to the task. Should the chancellor allow the best interest of a child to be determined on lopsided proof? Or should she let the better-represented side play “gotcha!”? Neither. As Albright itself reiterates, the polestar consideration is the best interest of the child. In her role as the child’s superior guardian (Carpenter v. Berry, 58 So.3d 1158, 1163 (Miss. 2011)), the chancellor has the duty to make sure that there is adequate proof in the record before making a decision. Rule 614 and the judge’s authority to reopen or leave the record open are the tools that the judge can put to good use.

It goes without saying that this considerable power should be exercised with discretion. There is the well-worn tale of the chancellor who interrupted counsel’s questioning of a witness and proceeded into his own lengthy cross examination. The attorney asked to approach the bench and told the judge, “Your honor, I don’t mind you questioning my witness, but please don’t lose the case for me.” So, a judge can be too fond of the sound of his own voice. The balance, perhaps, was laid out best by the Mississippi Supreme Court in Bumpus v. State, 166 Miss. 267, 144 So. 897 (1932): “It is true that ‘an overspeaking judge is no well-tuned cymbal,’ but, in language somewhat similar to that of Mr. Justice McReynolds, in Berger v. U. S., 255 U. S. 43, 41 S. Ct. 230, 65 L. Ed. 489, neither is an aphonic dummy a becoming receptacle for judicial power.”

JUDGE FAIR’S INVESTITURE TOMORROW

January 5, 2012 § Leave a comment

I was concerned that, up until Tuesday, there was no mention of Judge Gene Fair’s invesiture, much less appointment, on the Supreme Court’s web site. My chancery-court paranoia kicked in, and I wondered whether this was some new specie of persecution for us on the equity side.

My fears (exagerrated for this post, I assure you) were allayed by an anonymous insider, who reassured me that the silence had more to do with the holiday schedule than with an agenda. Whew.

If you can make Judge Fair’s ceremony tomorrow, I encourage you to do so. I plan to be there. Here’s the announcement:

December 29, 2011

An investiture ceremony for Judge Eugene L. Fair Jr. of the Court of Appeals of the State of Mississippi is scheduled for 10 a.m. Friday, Jan. 6, 2012, at the Gartin Justice Building, 450 High Street in Jackson.

The investiture will be webcast on the State of Mississippi Judiciary web site, www.courts.ms.gov. Members of the bench, bar and the public are invited.

Gov. Haley Barbour appointed Judge Fair to the District 5, Place 1 seat on the Court of Appeals. Judge Fair will replace Judge William H. Myers, who is retiring Dec. 31. The appointment is for one year. A special election will be held in November 2012 in the Court of Appeals district which includes Forrest, George, Greene, Hancock, Harrison, Jackson, Lamar, Pearl River, Perry, Stone and parts of Wayne counties.

Judge Fair, 65, of Hattiesburg, said, “I’m both honored and humbled by the appointment of the Governor.”

Gov. Barbour, his Chief of Staff Paul A. Hurst III, and Supreme Court Chief Justice Bill Waller Jr. will speak at the investiture. Former Mississippi Bar President George R. Fair, Judge Fair’s brother, will speak and will introduce special guests. Court of Appeals Chief Judge L. Joseph Lee will preside over the investiture ceremony.

Senior U.S. District Judge William H. Barbour Jr. will administer the oath of office.

Judge Fair’s wife, Dr. Estella Galloway Fair, will assist with the enrobing. Rev. Dr. Stephen Ramp, Judge Fair’s pastor at Westminster Presbyterian Church in Hattiesburg, will give the invocation. Rev. Dr. John C. Dudley of Hattiesburg, Administrative Presbyter of the Presbytery of Mississippi and Judge Fair’s former pastor, will give the benediction.

Judge Fair served for five years as a chancellor on the 10th Chancery Court. The district includes Forrest, Lamar, Marion, Pearl River and Perry counties.

Former Supreme Court Chief Justice Neville Patterson appointed him to the Mississippi Ethics Commission in 1984. Fair served on the commission for 20 years, including 19 years as vice-chair. He was board attorney for the Pat Harrison Waterway District 1988-1992.

Judge Fair grew up in Louisville. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Mississippi and a law degree from the University of Mississippi School of Law. During college, he was editor of The Mississippian for two years, and wrote for the Mississippi Law Journal. He helped pay his way through college with freelance writing for newspapers. He began working as a newspaper stringer at age 15, calling in sports scores and writing obituaries. He did freelance work for the Clarion-Ledger, the now defunct Jackson Daily News, the Meridian Star, the Associated Press and United Press International. He called his work as a news reporter and photographer “wonderful preparation to be a lawyer.”

He helped screen and recommend lawyers to fill judicial vacancies as a member of Gov. William Winter’s Judicial Nominating Committee. A similar group, Gov. Barbour’s Judicial Appointments Advisory Committee, recommended Fair to fill the vacancy on the Court of Appeals.

Fair ran unsuccessfully for election to the Supreme Court in 1988, and for the Court of Appeals in 1994. The 1994 race was for Position 1, District 5, the same position to which he has been appointed. He said, “I have thought about it (serving on an appellate court) for a long time. My uncle was Supreme Court Justice Stokes V. Robertson Jr., and I was greatly influenced by his dedication and love of the law. My cousin Charles Fair, having the same characteristics, had a similar influence on me.” His grandfather, also named Stokes Robertson, served as the first member of the House of Representatives from Forrest County and as Clerk of the House for four years. He was also Revenue Agent of the state of Mississippi, a statewide elective office later renamed State Tax Collector and abolished when William Winter held the office. His great-grandfather, G. C. Robertson, was the last Justice of the Peace of District 2, Perry County, before the county was split to form Perry and Forrest counties.

He served for four years on active duty with the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General’s Corps during the Vietnam War, attaining the rank of Lieutenant Commander, and spent five years as a reservist in the Jackson Naval J.A.G. Reserve Unit.

He practiced law in Hattiesburg from October 1972 to December 2006. During that time, he tried cases in 57 courthouses across the state. He was admitted to practice law in all state courts, the U.S. District Courts for the Northern and Southern Districts of Mississippi, the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court of Texas and the U.S. Supreme Court.

He served on the Mississippi Supreme Court Committee on Technology in the Courts 1988-1990, and on the Judicial Advisory Study Committee Technology Consulting Group 1993-1994.

He served as treasurer, secretary, vice-president and president of both the Young Lawyers Section of the Mississippi Bar and the South Central Mississippi Bar Association.

He held numerous leadership positions in the Mississippi Bar. He is a former member of the Board of Bar Commissioners, and is a Fellow of the Mississippi Bar Foundation and a Charter Fellow of the Young Lawyers.

He is a trustee, elder and Sunday School teacher at Westminister Presbyterian Church.

He is a former chairman of deacons, and was church treasurer for 18 years.

He is an Eagle Scout.

He has two daughters and four grandchildren. Melissa Fair Wellons M.D. is assistant professor at the University of Alabama Birmingham (UAB) School of Medicine. Julia Fair Myrick is a screenwriter and producer in Pasadena, Calif.

The 10-member Court of Appeals of the State of Mississippi is the state’s second highest court. The Supreme Court assigns cases to the Court of Appeals, and has discretionary review of its decisions. The Legislature created the intermediate appellate court in 1993 to speed decisions and relieve a backlog of appeals. The Court of Appeals began hearing cases in 1995.

‘NUF SAID

December 14, 2011 § 1 Comment

Following is the entire opinion rendered in the case of Denny v. Radar Industries Inc., 28 Mich. App. 294, 184 N.W.2d 289 (1970):

“The appellant has attempted to distinguish the factual situation in this case from that in Renfroe v. Higgins Rack Coating and Manufacturing Co., Inc. (1969), 17 Mich.App. 259, 169 N.W.2d 326. He didn’t. We couldn’t. Affirmed. Costs to appellee.”

Michigan Court of Appeals Judge J. H. Gillis deserves a medal for getting right to the point.

JUSTICE CARLSON PLANS TO STEP DOWN

November 15, 2011 § 2 Comments

Mississippi Supreme Court Presiding Justice George Carlson announced yesterday that he will step down when his term ends at the end of 2012. The vacancy created by his retirement is in the northern district.

Carlson, of Batesville, served for 19 years as a Circuit Judge in the 17th district. He was appointed by Governor Ronnie Musgrove to fill a vacancy on the Mississippi Supreme Court, and he has served on the high court for the last 11 years.

The justice said that he wants to spend more time with his family, alhough he continues to enjoy his work on the court.

He timed his announcement to allow time for careful consideration and planning for the campaign in the 33-county northern Supreme Court district.

His announcement at the Mississippi Judiciary web site is here. The Clarion-Ledger article, which mimes most of the official announcement instead of doing its own reporting, is here.

MORE HISTORY OF THE LAUDERDALE COUNTY COURT HOUSE

October 21, 2011 § Leave a comment

I posted here about the evolution of the Lauderdale County Court House, which included various historical photos of the building.

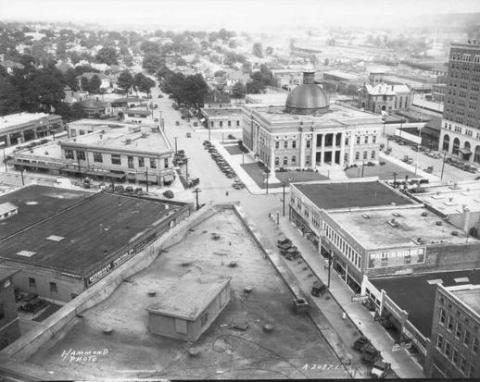

Below is a photo of Meridian looking east-southeast, obviously from a vantage point in the Threefoot Building, Meridian’s 16-story Art Deco icon, which had been built in 1929. The Lauderdale County Court House is the domed, Beaux-Arts-style building in the right center. The photo had to have been taken before 1939, because that is the year when the WPA work removed the dome, replaced it with a squarish jail, and transformed the façade from Beaux Arts to Art Deco. The photo, then, had to have been taken between 1929 and 1939.

If you compare this photo to some in the prior post, you will notice that the statues that originally adorned the court house roof above the west-facing columned entrance are removed. The Confederate memorial has been installed on the northwest corner of the lawn.

In other details of the photo, look to the right of the court house, east of and about a block from the Lamar Hotel building, and you will see the old jail that predated the one installed atop the court house during the WPA renovation.

You will also notice the residential neighborhoods to the east that extend in this photo within a block of the court building. I imagine some of the more everyday lawyers strolled to work from home in those neighborhoods back when this photo was taken. The more prosperous barristers lived in the mansions along Eighth Street, or around Highland Park, or in the ample residences on Twenth-Third and Twenty-Fourth Avenues.

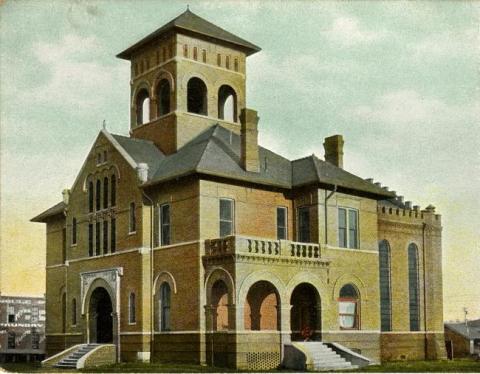

Here is a post-card photo of the jail building. Notice the Soulé foundry building to the left (east) of the jail. Its location will give you a clue as to the site of the old jail.

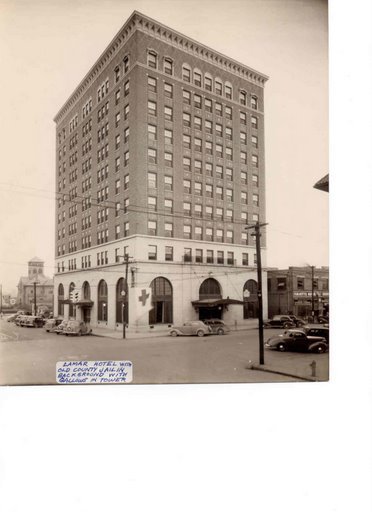

And below is a photo of the Lamar Hotel looking southeast, with the jail to the left, or east. Notice the caption, “Lamar Hotel with old County Jail in background with gallows in tower.” Before the state employed a travelling electric chair, executions for capital offenses were carried out in the various counties by hanging. Meridian, in forward-looking fashion, had a permanent gallows for the purpose, rather than having to go to the expense of constructing an ad-hoc apparatus as the need arose. Even back in those days, Lauderdale County had innovative leadership.

WHAT IS THE EXTENT OF THE DISABILITIES OF MINORITY?

October 17, 2011 § 3 Comments

Minors can not act for themselves. We call this the “disability of minority,” and the chancery court is charged with protecting their rights. Alack vs. Phelps, 230 So. 2d 789, 793 (Miss. 1970).

The principle of minority disability is in keeping with the ancient maxim of equity that “When parties are disabled equity will act for them.” Griffith, Mississippi Chancery Practice, Section 34, page 37 (1950 ed.). More than 130 years ago, in the case of Price vs. Crone, 1871 WL 8417, at 3 (1870), the Mississippi Supreme Court stated:

“Nothing is taken as confessed or waived by the minor or her guardian. The court must look to the record and all its parts, to see that a case is made which will warrant a decree to bind and conclude [the minor’s] interest, and of its own motion, give the minor the benefit of all objections and exceptions, as fully as if specially made in pleading … There being no power in the infant to waive anything, a valid decree could not be made against her, unless there has been substantial compliance with the requirements of the law, in the essential matters.” [Emphasis added]

Thus, the chancery court can and should act on its own initiative to protect and defend the minor’s interest.

In the case of Khoury vs. Saik, 203 Miss. 155, 33 So.2d 616, 618 (Miss. 1948), the supreme court held that, “Minors can waive nothing. In the law they are helpless, so much so that their representatives can waive nothing for them …” This is so even where the minor has pled, appeared in court, and even testified.” Parker vs. Smith, et al., 150 Miss. 849, 117 So. 249, 250 (Miss. 1928).

Our modern MRCP 4(e) embodies these concepts wherein it specifically states that, “Any party … who is not an unmarried minor … may … waive service of process or enter his or her appearance … in any action, with the same effect as if he or she had been duly served with process, in the manner required by law on the day of the ate thereof.” There is no provision in MRCP 4 that permits a minor to join in an action on his or her own initiative, or to waive process; in fact, the express language of Rule 4 makes it clear that such is not permitted.

It is a long-held fundamental of Mississippi law that process must be had on infants in the form and manner require by law, and a decree rendered against minors without service in the form and manner required by law is void as to them, as they can not waive process. Carter vs. Graves, 230 Miss. 463, 470, 93 So.2d 177, 180 (Miss. 1957).

The purpose of the protective posture of the law is clear: “Minors are considered incapable of making such decisions because of their lack of emotional and intellectual maturity.” Dissent of Presiding Justice McRae in J.M.M. vs. New Beginnings of Tupelo, 796 So.2d 975, 984 (Miss. 2001). During the formative adolescent years, minors often lack the experience, perspective and judgment required to recognize and avoid choices that are not in their best interest. Belotti vs. Baird, 443 U.S. 622, 634, 99 S.Ct. 3035, 3043 (1979).

In the case of In the Matter of R.B., a Minor, by and through Her Next Friend, V.D. vs. State of Mississippi, 790 So.2d 830 (Miss. 2001), R.B., an unmarried, seventeen-year-old minor, became pregnant and sought chancery court approval of an abortion, pursuant to MCA § 41-41-55(4). The decision described her as, ” … of limited education, having attended school through the eighth grade,” and largely ignorant of the medical and legal implications of her request. Id., at 831. The decision reveals that the chancellor went to great pains to develop the record that the young girl had not been informed of the possible complications of the surgical procedure, that she was emotionally fragile and susceptible to mental harm, that there were services available to the youngster of which she was unaware, and other pertinent factors. Id., at 834. The supreme court upheld the decision of the chancellor, saying,

“R.B. has failed to persuade us that she is mature enough to handle the decision (for an abortion) on her own. The record does not indicate that the minor is capable of reasoned decision-making and that she has considered her various options. Rather the decision shows that R.B.’s decision is the product of impulse.” Id., at 834.

It has long been the law in Mississippi that all who deal with minors deal with them at their peril, since the law will take extraordinary measures to guard them against their own incapacity.

The principle of minority disability is ingrained in many facets of Mississippi law:

- Minors may not vote. Article 12, Section 241, Mississippi Constitution.

- Minors may not waive process. MRCP 4(e).

- Minors may not select their own domicile, but must have that of the parents. Boyle vs. Griffin, , 84 Miss.41, 36 So. 141, 142 (Miss. 1904); In re Guardianship of Watson, , 317 So.2d 30, 32 (Miss. 1975); MississippiBand of Choctaw Indians vs. Holyfield, 490 U.S. 30, 40; 109 S.Ct. 1597, 1603 (1989).

- Minors may not enter into binding contracts regarding personal property or sue or be sued in their own right in regard to contracts into which they have entered. MCA § 93-19-13.

- Minors may not have an interest in an estate without having a guardian appointed for them. MCA § 93-13-13.

- Minors may not purchase or sell real property, or mortgage it, or lease it, or make deeds of trust or contracts with respect to it, or make promissory notes with respect to interests in real property without first having his or her disabilities of minority removed. MCA § 93-19-1.

- Minors may not be bound by contracts for the sale of land, and may void them at their option.Edmunds vs. Mister, 58 Miss. 765 (1881).

- Minors may not choose the parent with whom they shall live in a divorce or modification; although they may state a preference, their choice is not binding on the chancellor. MCA § 93-11-65; Westbrook vs Oglesbee,606 So.2d 1142, 1146 (Miss. 1992); Bell vs. Bell, 572 So.2d 841, 846 (Miss. 1990). Minors may not after emancipation be bound by or enforce contracts entered into during minority except by following certain statutory procedures. MCA § 15-3-11.

- Minors may not legally consent to have sexual intercourse. MCA § 97-3-65(b).

- Minors may not legally consent to be fondled. MCA § 97-5-23(1).

- Minors are protected by an extended statute of limitations. MCA § 15-1-59.

It’s important to be aware of the legal status of the persons with whom you are dealing in land transactions, estates, contracts, and many other legal matters. In Mississippi, minors have many legal protections and disabilities that the courts will zealously guard.

THE POWER OF NOW FOR THEN

September 28, 2011 § Leave a comment

Unlike mere mortals, chancellors have the power to reach back into the past and take action as effectively as if had actually been done back then. It’s called nunc pro tunc — Latin for now for then — and here is how it works:

“This Court has stated that ‘[n]unc pro tunc signifies now for then, or in other words, a thing is done now, which shall have [the] same legal force and effect as if done at [the] time when it ought to have been done.’ In re D.N.T., 843 So. 2d 690, 697 n.8 (Miss. 2003) (quoting Black’s Law Dictionary 964 (5th ed. 1979)) (emphasis added). This Court has further articulated that

[n]unc pro tunc means ‘now for then’ and when applied to the entry of a legal order or judgment it does not refer to a new or fresh (de novo) decision, as when a decision is made after the death of a party, but relates to a ruling or action actually previously made or done but concerning which for some reason the record thereof is defective or omitted. The later record making does not itself have a retroactive effect but it constitutes the later evidence of a prior effectual act.

Thrash v. Thrash, 385 So. 2d 961, 963-64 (Miss. 1980) (emphasis added).”

The above language is from the MSSC decision in Irving v. Irving, decided August 18, 2011.

We’ve talked here before about Henderson v. Henderson, another nunc pro tunc case that reached back two years to effectuate a divorce judgment that had erroneously never been entered with the clerk.

Years ago I tried a consent divorce case in Wayne County involving only property issues between an elderly husband and wife. Chancellor Shannon Clark rendered an opinion from the bench at the conclusion of trial and directed me to draft the judgment, which I did the next day and mailed to counsel opposite in Waynesboro. Before the other attorney could approve the judgment and return it to me, my client suddenly died. Judge Clark later signed a judgment nunc pro tunc, and the other side appealed. In White v. Smith, Admrx of Estate of White, 645 So.2d 875, 882 (Miss. 1994), the MSSC upheld the trial judge’s action, quoting a Florida case that held, ” … recordation of a final decree is a procedural and ministerial act, that a decree when recorded is but evidence of judicial action already taken and that a failure to perform the act of recording may be remedied by an order nunc pro tunc.”

I’ll leave it to you to conjure up some situations in which you can ask the chancellor to act now for then to pull your irons out of the fire.

“ASK NOT FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS …”

September 27, 2011 § 3 Comments

Cell phones in court rooms have given rise to some pretty funny situations.

I have seen judges fly into a blind rage at the sound of a ringing cell phone during a trial. And I have seen judges act benignly, at most emitting a resigned sigh to the techno intrusion. The range of reactions is almost infinite.

In the early days of cell phones in our district, Judge George Warner was in the more-or-less rageful category. Since people were unaccustomed to the new contraptions, it happened fairly often that they neglected to turn them off before entering the court room. So it was that chirping cell phones could be heard as witnesesses droned on in trials. The high frequency ringtones irked Judge Warner the most. He would stop the witness, demand to know whence the intrusion arose, and direct the bailiff to confiscate the offending instrument forthwith. Since it never happened to me or my client personally, I never discovered what became of all those seized phones. I imagined that there was a warehouse with stockpiles of them, some buzzing or beeping merrily along unanswered, with no human to put them to rest.

In time, as people became used to the electronic marvels and the instruments became more sophisticated, we learned to put our phones on “vibrate.” We males also learned not to carry them in our pants pockets in the court room when the phone was on vibrate, lest sudden vibrations in that region cause a surprised yelp or leap into the air inconsistent with court room decorum.

And so the practice became to place the vibrating phone on counsel’s table, where it could vibrate away without consequence. Or so we thought. In one trial I had, I was cross examining the witness at the only court room podium in Judge Mason’s court. The podium was next to counsel opposite’s table. As I questioned the witness, I was distracted by a sound akin to a swarm of bees to my right. After a minute I looked over and there was Robbie Jones’s cell phone lit up like a Christmas tree, vibrating loudly on the oak table. The table was amplifying the sound. Every time the phone vibrated, it inched across the table like a buzzing, manic seventeen-year locust. Jones sat there and watched the creature head toward the edge of the table. Right before it lurched off into oblivion, I snatched it and handed it to Jones with a flourish. We two lawyers were quite amused. Judge Mason not so much.

When I took the bench, it became my practice not to react to the mere blirping of a cell phone in my court room. Most callees react with mortification at their oversight, and commence with comic spasmic desperation to put a stop to the interruption. I figure their embarassment is punishment enough. Of course, my reaction would be different at the second offense by the same person, or if the offender began a cell phone conversation in the court room.

Most judges nowadays react by taking up the phone and holding it until the end of the day or the trial. Judge Gene Fair of Hattiesburg related his woeful experiences:

On one Friday afternoon in Poplarville, early in my first term as a judge, it was announced by me just before beginning of a trial that ringing cell phones during a trial would be considered, as allowed and provided by a Uniform Chancery Rule, to be contempt of court punishable by a fine of $50.00.

Forty (40) minutes into the trial my phone rang. I recessed Court, wrote a check for $50.00, put my phone in chambers and announced that future fines would be $25.00, and would be paid at the close of proceedings, when the offending phone would be returned to its owner by the bailiff. .

It was funny to almost everyone in the Courtroom, as was my payment of $25.00 the following Monday in Purvis, when two lawyers joined me in paying the Clerk a total of $75.00. As Justice Mike Sullivan pointed out when he showed up significantly late for a trial because of having gone to the wrong courthouse and wrote a $100.00 check to the clerk for his contempt, “I have learned a lesson. I hope someone else has also.”

I have had to pay only $25.00 this year, and it is September.

So far in my time on the bench I have paid a total of $250 in four of five of my counties. There are only one or two other offenders who have gone as high as $100.00. In Perry County, the smallest county and the one of which my great-grandfather was a Justice of the Peace, I have a pristine record. It is probably the result of only three one week terms and a few ex-parte days schedule for my presence there.

That oh, so convenient cell phone with its pleasant bell-tone. Will it toll for thee?