The key to “McKee”: Analyzing The Reasonableness of Attorney’s Fees

November 20, 2024 § 3 Comments

By: Donald E. Campbell

In two recent cases the Mississippi Court of Appeals has addressed the award of attorney’s fees in estate matters. In the first case, Estate of Watson v. Watson, 2024 WL 4354006 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024) the court reversed the chancellor based on the award of attorney’s fees over other creditor claims in an insolvent estate. While distribution of assets in an insolvent estates is a topic for another post, in opinion the court notes that the chancellor held that the fees were “reasonable and appropriate” without doing an appropriate analysis under McKee v. McKee, 418 So. 2d 764 (Miss. 1982). McKee sets out seven factors that a court should consider when evaluating attorneys fees. These factors, have become known as the “McKee factors”.

Similarly, in Estate of Stimley v. Merchant, 2024 WL 4439985 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024), an attorney representing an estate sought approval of attorney’s fees in the amount of $48,167.75. After a hearing, the chancellor said the fees were an “astronomical sum”, and would issue an opinion as to what would be a “reasonable fee in light of … services rendered.” Ultimately the court issued an order which provided the following — with no further explanation:

The law firm appealed the judgment which was assigned to the court of appeals. Writing for a unanimous court (Judge Carlton not participating), Judge Lawrence held that the chancellor erred in failing to apply the McKee factors in determining the appropriate amount of fees.

Right to attorney’s fees

The following statute provides for “reasonable” fees to be paid to an attorney providing services to an estate.

Miss. Code Ann. § 91-7-281. Attorney’s Fees

In annual and final settlements, the executor, administrator, or guardian shall be entitled to credit for such reasonable sums as he may have paid for the services of an attorney in the management or in behalf of the estate, if the court be of the opinion that the services were proper and rendered in good faith. Where the executor, administrator, or guardian acts also as attorney, the court may allow such executor, administrator, or guardian credit for his reasonable compensation as attorney in lieu of his compensation as executor, administrator, or guardian.

The attorney is entitled to “reasonable” fees if the services “were proper and rendered in good faith.” The determination of reasonableness is left to the discretion of the chancellor and an appellate court will review “the reasonableness of the [attorney’s fees] award only for an abuse of discretion, and we will not reverse unless the award is manifestly erroneous or amounts to a clear or unmistakable abuse of discretion.” (¶7). The court ultimately determined that the failure to do any analysis of the McKee factors warranted reversal.

Professor’s Thoughts

I thought it might be worthwhile to examine what is required for an adequate analysis of the McKee factors. As a starting point, chancellors are given a lot of discretion in awarding fees (reviewed for an abuse of discretion). Furthermore, the Stimley court notes “‘the lack of a factor-by-factor analysis does not immediately warrant a reversal.” However, there must be proof ‘support[ing] an accurate assessment of fees under the McKee criteria” (¶ 8) and “the mention of the McKee analysis is not enough to support a chancellor’s award of attorney’s fees.” (¶10).

So the question is: what does a sufficient McKee analysis look like? In footnote 9 of the Stimley opinion, the court references Mauck v. Columbus Hotel, 741 So. 2d 259 (Miss. 1999) as a case where the court did an adequate analysis. Therefore, in the discussion below, the judgment entered by the Chancellor in Mauk will be considered.

McKee Factors: Where did they come from?

McKee was a divorce case in which the chancellor awarded attorney’s fees to the wife’s attorneys and the Supreme Court reversed, holding that the amount of fees awarded was excessive. In granting guidance to courts in determining the appropriate amount of fees the Court held:

In determining an appropriate amount of attorneys fees, a sum sufficient to secure one competent attorney is the criterion by which we are directed. Rees v. Rees, 194 So. 750 (Miss. 1940). The fee depends on consideration of, in addition to the relative financial ability of the parties, the skill and standing of the attorney employed, the nature of the case and novelty and difficulty of the questions at issue, as well as the degree of responsibility involved in the management of the cause, the time and labor required, the usual and customary charge in the community, and the preclusion of other employment by the attorney due to the acceptance of the case.

We think it is not the best practice to estimate the time expended as the basis for a fee as the approximation is more susceptible to error, and thus more suspect than properly maintained time records. Estimates, however, can properly be considered by the court but the attorney who does so should have a clear explanation of the method used in approximating the hours consumed on a case. We are also of the opinion the allowance of attorneys fees should be only in such amount as will compensate for the services rendered. It must be fair and just to all concerned after it has been determined that the legal work being compensated was reasonably required and necessary.

Most of these factors were first set out by the Fifth Circuit in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Exp., Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974) and then cited with approval by the United States Supreme Court in Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983). There are 2 factors adopted by the Court in McKee that are not in the cases or the ethics rule: (1) relative financial ability of the parties, and (2) responsibility required in managing the case. I pulled the briefs from McKee to see if the parties cited to authority for these elements — but they did not. So these two factors are unique to Mississippi’s evaluation of attorney’s fees and, at least with regard to the ability to pay factor, may not be appropriate in every case.

The test for attorney’s fee is really a modified-McKee approach

If you look at cases after McKee what you see is that courts will cite to the factors set out in Rule 1.5 (which does not include the two referenced above) and call these the “McKee factors.” For example, in Mississippi Power and Light v. Cook, 832 So. 2d 474 (Miss. 2002), the Supreme Court set out the Rule 1.5 factors, cited McKee, and then said: “These factors are sometimes referred to as the McKee factors.” Id. at 486. Therefore, the standard for determining a reasonable attorney’s fee is best viewed as requiring an analysis relevant Rule 1.5 factors and the additional McKee factors if relevant.

None of the following factors are determinative, but should considered as a whole in evaluating a particular fee.

(1) Relative financial ability of the parties

This is the most unusual of the factors set out in McKee to evaluate the reasonableness of an attorney’s fee. This factor is not found in Rule 1.5 or in any other state lists of reasonableness factors. The question of whether a fee is reasonable not the same question as whether the fee is collectible. It may be that a client will never be able to pay a fee — but that does not make the fee unreasonable.

I think that this factor was listed because it is relevant in domestic relations cases. For example, in Dauenhauer v. Dauenhauer, 271 So. 3d 589 (Miss. Ct. App. 2018), the wife in a divorce action stipulated that the amount of attorney’s fees sought by her husband was reasonable, but argued that it was not appropriate to award fees because of her inability to pay. The court of appeals agreed and held that the award of fees was not appropriate.

Therefore, this factor will be relevant in domestic cases, but is not relevant in other situations where the ability to pay is not a relevant consideration.

(2) The skill and standing of the attorney employed [Rule 1.5(a)(7)]

An attorney that specializes in a particular area of law or who is well respected in a particular area of law may be in high demand and therefore able to charge a higher fee than someone without such reputation or skill. The Mauck court titles this factor as “The Skill Requisite to Perform the Legal Services Properly”:

(3) Novelty and difficulty of issues in the case [Rule 1.5(a)(1)]

If an attorney takes on a case of unusual difficulty or that raises a novel claim, fees that might otherwise be excessive can be considered reasonable: “Cases of first impression generally require more time and effort on the attorney’s part. Although this greater expenditure of time in research and preparation is an investment by counsel in obtaining knowledge which can be used in similar later cases, he should not be penalized for undertaking a case which may ‘make new law.’ Instead, he should be appropriately compensated for accepting the challenge.” Johnson, 488 F.2d 714 at 718.

(4) The responsibility required in managing the case

This is another factor that is unique to McKee and is not found in Rule 1.5 (or in the Johnson factors). In fact, in my research I cannot find any other jurisdiction that has this factor. I am not sure what the Supreme Court relied upon in adopting this factor. It is not referenced in the parties’ briefs in McKee. However, in the McKee briefs there is a great deal of discussion of the numerous lawyers that were involved and the time that they spent on the case. This element may be better framed as a factor that is in Rule 1.5(a)(4): The amount involved and the results obtained.

Assuming this factor is meant to cover the amount involved and the results obtained, the question is whether the fee is in line with the nature of the representation. For example, in Matter of Fordham, 668 N.E.2d 816 (Mass. 1996), a lawyer charged approximately $50,000 (227 hours) in representing a defendant in a DUI case. The testimony received indicated that the lawyer obtained a very good outcome for the defendant (the case was dismissed based on a novel argument), but even the lawyer’s expert testified that she had never heard of a fee in excess of $10,000 in a DUI case. Therefore, even if the lawyer was entitled to a “bonus” for obtaining favorable results, the $50,000 charge was clearly excessive. On the other side, if the matter involved a great deal of money and the lawyer is able to obtain favorable results, a larger fee may be warranted.

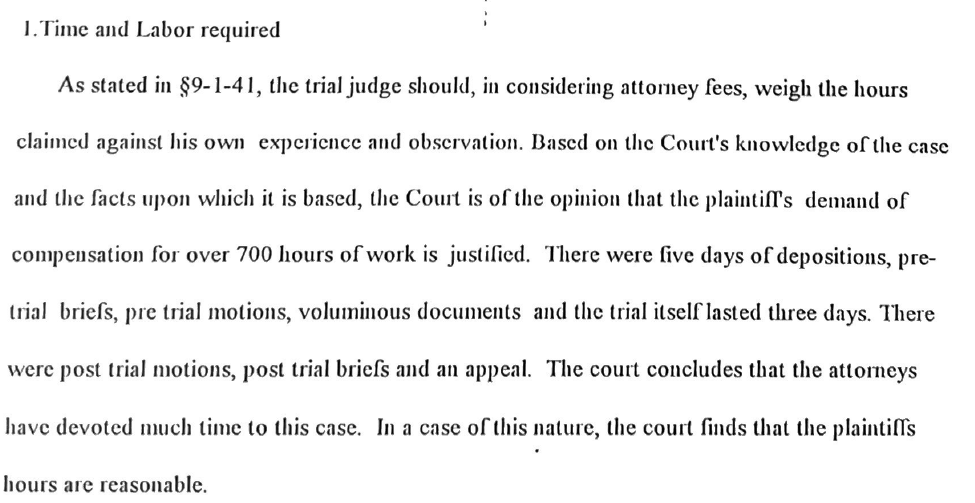

(5) Time and labor required [Rule 1.5(a)(1)]

A case that requires a lot of time and effort to resolve would justify a larger fee amount than one where very little effort is required the matter. In this regard, judges should bring into consideration their own background and experience: “The trial judge should weigh the hours claimed against his own knowledge, experience, and expertise of the time required to complete similar activities. If more than one attorney is involved, the possibility of duplication of effort along with the proper utilization of time should be scrutinized. The time of two or three lawyers in a courtroom or conference when one would do, may obviously be discounted. It is appropriate to distinguish between legal work, in the strict sense, and investigation, clerical work, compilation of facts and statistics and other work which can often be accomplished by non-lawyers but which a lawyer may do because he has no other help available. Such non-legal work may command a lesser rate. Its dollar value is not enhanced just because a lawyer does it.” Johnson, 488 F.2d at 717.

The discussion below from Mauck involved cancellation of a lease.

Notice the court references Miss. Code § 9-1-41, which provides that a judge can rely on their “experience and observation” in evaluating whether the time spent on the case was reasonable:

Miss. Code Ann. § Evidence of attorney fees’ reasonableness

In any action in which a court is authorized to award reasonable attorneys’ fees, the court shall not require the party seeking such fees to put on proof as to the reasonableness of the amount sought, but shall make the award based on the information already before it and the court’s own opinion based on experience and observation; provided however, a party may, in its discretion, place before the court other evidence as to the reasonableness of the amount of the award, and the court may consider such evidence in making the award.

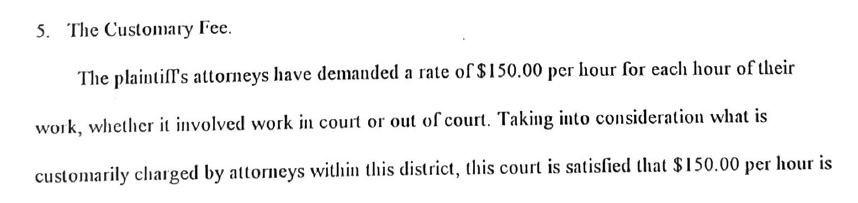

(6) The usual and customary fee charged in the community [Rule 1.5(a)(3)]

The baseline to determine whether a fee is reasonable or excessive is what a competent lawyer would charge for the service in the community. This is the loadstar approach — “the most useful starting point for determining the amount of a reasonable fee is the number of hours reasonably expended on the litigation, multiplied by a reasonable hourly rate.” BellSouth Communications v. Bd. of Supervisors, 912 So. 2d 436, 446-47 (Miss. 2005).

The factors discussed above may justify a higher fee than would normally be charged, but for a run-of-the-mill case, the fee should be in line with what would ordinarily be charged for the type of case by lawyers in the community.

(7) Whether the attorney was precluded from undertaking other employment by accepting the case [Rule 1.5(a)(2)]

An attorney who agrees to accept a case and spend time on it to the exclusion of other cases would be entitled to charge a larger fee than an attorney who just accepted a case as part of the ordinary book of business. This is particularly relevant where the lawyer has other available business which they must turn down because representation of the client would result in a conflict of interest. This factor would also cover situations where a lawyer is brought in at the last minute to handle a matter and has to make the client’s case a priority – delaying the lawyer’s other work. This is more than just the lawyer’s business decision to accept a case and refuse another. This is meant to cover a situation where a lawyer could have other business, the client is aware that the lawyer, in taking the client’s case, will be precluded from accepting the other matter (that is why the Rule requires that the situation be “apparent to the client”).

The Mauk court judgment:

Factors were not discussed in McKee, but are included Rule 1.5:

(8) Time limitations imposed by the client or the circumstances [Rule 1.5(a)(5)]

This is meant to cover a situation where a client needs work performed in an expedited manner or where the client comes to the lawyer at the last minute for legal assistance. In these situations, a lawyer would be entitled to charge more for a fee. Essentially the client is paying a premium for the lawyer to drop everything they are doing to handle the client’s matter.

(9) The nature and length of professional relationship with the client [Rule 1.5(a)(6)]

This factor is meant to address situations where a lawyer and client have a long-standing relationship. A long-standing client who has accepted increased fees over time and who has presumably been pleased with the lawyer’s representation should not be able to, in hindsight, argue that the fee is unreasonable (essentially arguing that another lawyer would have charged them less). This factor recognizes good will that develops over time between a lawyer and client has value.

(10) Whether the fee is fixed or contingent [Rule 1.5(a)(8)]

Questions of reasonableness will almost always arise in the context of an hourly rate fee. Contingent fees are not governed by the same standards of reasonableness. There are a couple of reasons that cases that are taken on a contingency fee basis would justify a higher fee than one taken on an hourly rate. The first reason is based in public policy – contingency cases allow those who could not otherwise afford a lawyer to have their case heard. Second, the lawyer who accepts a contingency fee case is taking the risk that they will not recover anything. Acceptance of this risk justifies the recovery of a higher amount of fees. Of course, if the lawyer takes a case where there is no uncertainty in the plaintiff’s right to recovery. For example, in Attorney Grievance Comm’n v. Kemp, 496 A.2d 672 (Md. Ct. App. 1985), the court held that recovery under a contingency fee was unreasonable where there was a statutory right to recover certain insurance proceeds. The court noted: “[w]hen there is virtually no risk and no uncertainty, contingent fees represent an improper measure of professional compensation.” Id. at 676.

A contingency fee can also be unreasonable if the percentage charged is unusually high.