When can a person be presumed dead? An analysis of Miss. Code Ann § 13-1-23 and the 2024 Amendment

October 30, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

There is a longstanding common law rule that a person who has been absent for an extended period of time can be presumed to be dead. See Thayer, A Preliminary Treatise on Evidence at the Common Law pp. 319-324 (1898). Mississippi has codified this common law rule since at least 1856, and the statute remained largely unchanged until 2024. This post will cover first the long-standing part of the statute and then the 2024 Amendment.

7 Years Absent or Concealed Can be Presumed Dead

Mississippi Code Ann. Section 13-1-23(1) provides:

(1) Except as otherwise provided in subsection (2) of this section, a person who shall remain beyond the sea, or absent himself or herself from this state, or conceal himself or herself in this state, for seven (7) years successively without being heard of, shall be presumed to be dead in any case where the person’s death shall come in question, unless proof be made that the person was alive within that time. Any property or estate recovered in any such case shall be restored to the person evicted or deprived thereof, if, in a subsequent action, it shall be proved that the person so presumed to be dead is living.

Here are some cases where the statute was applied and interpreted:

- In Learned v. Corley, 43 Miss. 687 (Miss. 1870), Henry Augustus sailed from New York in 1856 en route to Spain. After five days at sea there was a storm and neither the ship nor any of its passengers were heard from again. Ten years later, in 1866, a hearing was held, and he was presumed to be dead under the statute.

- In Manley v. Patterson, 19 So. 236 (Miss. 1896), the Mississippi Supreme Court interpreted the phrase “absenting” in the statute. In that case, a husband, wife, and two children disappeared after the husband became “involved in some trouble” in Hazlehurst. The children were left property interest in the will of their grandmother. A guardian was appointed to protect the children’s interest. The contingent beneficiaries of the property under the will sought a declaration that the children were presumed dead. The Supreme Court refused to allow the party to rely on the presumption of death statute, because the statute requires proof that the person “absent” or “conceal” themselves, which requires the ability to do so by a person’s own volition. The presumption of death cannot apply to children who, “by reason of their tender age, [are incapable] of ‘absenting’ themselves from the state, or of ‘concealing’ themselves within it.” The court noted that evidence could still be put on to establish that the children were actually dead, but the party could not utilize the presumption of death.

- In Frank v. Frank, 10 So. 2d 839 (Miss. 1942), Isom Frank had a life insurance policy payable to his wife, with the contingent beneficiary being his next of kin. Frank’s purported wife was Ollie Lee. The problem was that Ollie Lee married Dan Evans in 1912. Shortly after the marriage Dan moved to Arkansas. None of Dan’s Mississippi relatives knew where he was. In 1927, Ollie wrote to Dan’s sister in Arkansas asking about his whereabouts. The sister responded that Dan had drowned. Thereafter, in 1935, assuming Dan was dead, Ollie Lee married Isom Frank. However, at some point Dan reappeared. The Court (over two strong dissents), held that the statutory presumption of death was rebutted by the fact that Dan reappeared. Therefore, Ollie’s second marriage to Isom Franks was invalid, and she was not entitled to the insurance proceeds as the wife of Isom Franks.

- In Martin v. Phillips, 514 So. 2d 338 (Miss. 1987), John Martin and his wife, Grace Martin owned 340 acres in Grenada County as joint tenants. Thereafter, on January 20, 1969, John parked his car near the Grenada spillway and disappeared. In 1976 (7 years after his disappearance), Grace filed an action in the Grenada County Chancery Court to have John declared dead under the statute. The Chancery court held that there was sufficient evidence to raise a presumption that John was dead. Thereafter, in 1977, Grace sold the property she held as joint tenants with John to the Phillip’s for $95,000. In a twist that would make soap operas jealous, John reappeared in August 1983 (the court notes that there was no explanation for this “spectral reemergence from the dead”). John filed a petition in chancery court to have the order declaring him dead set aside, and to have the property he owned restored to him. John based his claim on the statute, which provides that, if the person who is declared dead is later determined to be living, “[a]ny property or estate recovered in any such case shall be restored to the person evicted or deprived thereof….” The chancellor set aside the declaration of death but refused to void the conveyance of the property. The Supreme Court reversed the chancellor, holding that it was error to grant a 12(b)(6) dismissal without developing the facts to show the purchasers of the property from Grace did not actually know that John was still alive and that they relied on that fact in purchasing the property. Essentially they would have to show that they were good faith purchasers.

- The most recent case citing the statute is Matter of Johnson, 312 So. 3d 709 (Miss. 2021). In that case, Ashley filed a petition in the Hinds County Chancery Court asking the chancellor to declare her father, Audray Johnson, dead, arguing that he “had been gone from his physical body for more than seven years and should be presumed dead.” Audray (who had changed his name to Akecheta Andre Morningstar), testified at a hearing on the petition that Audray’s “spirit expired more than seven years ago, and Morningstar now occupies Audray’s physical body.” The supreme court quoted the chancellor with approval in affirming the denial of the declaration of death:

The reality is that we are identified by our physical body. Our physical body is given a birth certificate and social security number to identify our person and ultimately a death certificate. Our physical body can be identified by our DNA, fingerprints, and physical appearance. It is uncontested that the physical body of Audray Johnson is the body Morningstar now occupies.

Id. at 711.

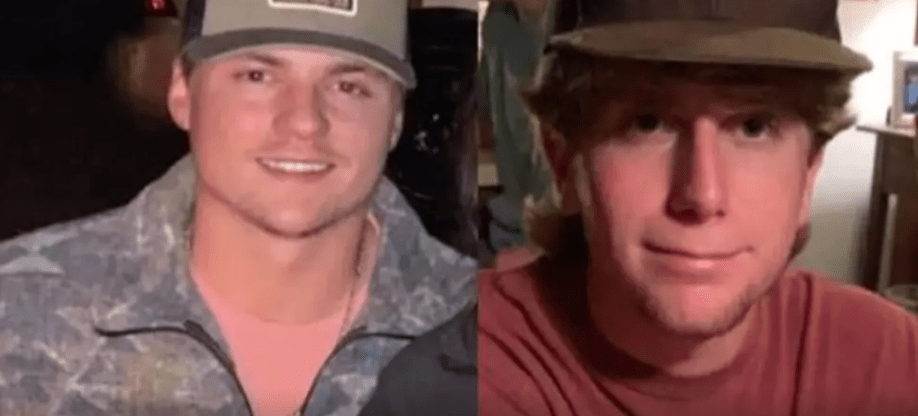

2024 Amendment: Zeb Hughes Law

On December 3, 2020, Zeb Hughes (21) and Gunner Palmer (16) went missing while hunting ducks on the Mississippi River near Vicksburg. While search teams found their boat and some hunting equipment, the bodies of the boys have never been recovered. Now, more than three years after the disappearance, under the statute discussed above, the families would still have to wait four more years before a death certificate could be issued. The mother of Zeb Hughes, who worked to have the law amended noted that there are a number of times she has needed a death certificate to handle affairs on behalf of her son and could not do so because seven years have not passed.

The 2024 Amendment, which is titled the “Zeb Hughes Law” provides that a person who has undergone a “catastrophic event that exposed the person to imminent peril or danger reasonably expected to result in loss of life” and whose absence cannot be explained after a diligent search is presumed to be dead if there is uncontradicted testimony from those having “firsthand knowledge of the event” (law enforcement officers, first responders, search and rescue personnel, eye witnesses, etc.) that the person died in the “catastrophic event.” The hearing can be held 2 years after the event and the “loss of life shall be proven by clear and convincing evidence.” Notice of the hearing must be provided to the “coroner, the district attorney and the sheriff of the county” in which the event occurred.” If the evidence is sufficient to establish the presumption of death, the death is presumed to have occurred at the time of the catastrophic event.

The law also amended Miss. Code Ann. § 41-57-8, and requires the State Registrar of Vital Statistics to issue a death certificate upon receipt of a court order finding a presumption of death.

Professor’s Thoughts

I first heard about this amendment at a CLE for public defenders. The speaker before me was talking about the impact of this amendment in the criminal prosecution/defense world in cases where someone is missing and foul play is suspected. Looking at the statute, I think it is going to raise some interesting issues in the future, for example:

- What is meant by “catastrophic event”? There is no definition of the term. Does the phrase mean situations where a person has gone missing — like Zeb Hughes? Is the catastrophic event the presumed drowning? Is it the event that caused them to drown — Zeb’s mother thinks it was the turbulent waters of the Mississippi River although that is speculation. The speaker at the CLE said that he believed that the phrase “catastrophic event” was intended to be more like a hurricane or flood. That definition of catastrophic event would not cover the missing person situation without some kind of natural disaster or other widespread event. This interpretation is justifiable if based on the text but not if you look at legislative intent (and the title of the amendment).

- There is also a question of what to include on the death certificate. A medical examiner may be unwilling to sign off on a death certificate that states a presumed cause of death without having a body to confirm the cause of death.

- There is also no provision for what happens if the person presumed to be dead ultimately reappears. The amendment to the statute specifically states that section (1) which provides that if a person presumed dead appears they are entitled to have their property restored.

Leave a comment