The need to clarify the “reasonable necessary” standard with regard to easements by necessity

October 18, 2024 § Leave a comment

By: Donald Campbell

Word v. U.S. Bank, 2024 WL 4489615 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024), is a case decided by the Mississippi Court of Appeals about an easement by necessity. While the court ultimately reached the correct decision based on Mississippi law, the opinion included some analysis that needs to be clarified/corrected in future cases for the benefit of practitioners and judges.

Facts of Word v. U.S. Bank

There are two parcels at issue in the case — from a common owner named Zeno Griffin. The parcel ultimately owned by William Word was conveyed by Griffin in 1996. Word purchased the lot in 2019. Thereafter, Griffin conveyed a second parcel in 1997 — this is the parcel that U.S. Bank ultimately obtained via foreclosure in 2019. This second parcel was landlocked when it was conveyed in 1997. Until 2019, access to the landlocked parcel was over a road on the Words’ property.

In early 2019 (prior to the bank’s foreclosure), Word blocked the road because he suspected the owners of the parcel were trafficking drugs. After Word blocked access, the owners began to use a route across another parcel of land (land retained by Zeno Griffin).

When the bank took ownership of the property, it filed suit in Perry County Chancery Court alleging that an easement by necessity was established over Word’s property and it had the right to continue to use the right-of-way that Word had blocked.

The case was assigned to Chancellor Michael C. Smith. Judge Smith ultimately held that the Bank had satisfied its burden to establish an easement by necessity and ordered Word to allow the Bank to cross his property. Word appealed.

The Appeal

The case was assigned to the Court of Appeals, and in an opinion by Judge Smith for a unanimous court (with Judge Wilson joining only part of the opinion and Judge Weddle not participating), the court reversed and rendered.

The Court of Appeal’s rationale was based on the following: (1) the Bank’s parcel was landlocked when it was severed from the commonly owned property, but at that time the Word property had already been severed (no longer owned by the common grantor Zeno Griffin); therefore, it was not possible to impose an easement by necessity over property that the common grantor did not own at the time of the severance creating the landlocked parcel; and (2) the bank “failed to provide any evidence at trial about the specific costs associated with using the available alternate route to access its parcel of land”. Specifically, the Court held: “even if U.S. Bank possessed a possible right to an easement by necessity over Word’s parcel, as in Hobby, it would still have constituted an abuse of discretion to grant the easement ‘without evidence of the alleged higher costs’ associated with utilizing the alternative available route.”

Professor Thoughts: Correct result but confused analysis of the “necessary” element of easement by necessity

I agree with the first part of the court of appeal’s opinion, but the second part is inconsistent with precedent and the purpose of implied easements, and provides confusing guidance about what is required to establish an easement by necessity.

Beginning with the part of the opinion that I agree with: At the time that the bank parcel was severed and landlocked, the Word parcel had already been sold. Therefore, to the extent there was an easement by necessity – it was over the property retained by the common grantor – not over the property that was not owned by the grantor at the time of the severance.

The part I disagree with: the court’s statement that the chancellor erred in failing to accept evidence of the cost to establish the easement (presumably over the property retained by Griffin). The rationale for requiring evidence of costs in the context of an easement by necessity is to establish whether there is necessity for an easement across the property retained by the grantor. The only reason cost is relevant is when the claimant has potential access to a public road but they argue requiring them to use that access is too expensive — and therefore an easement across their grantor’s property is necessary.

The problem begins with Hobby v. Ott

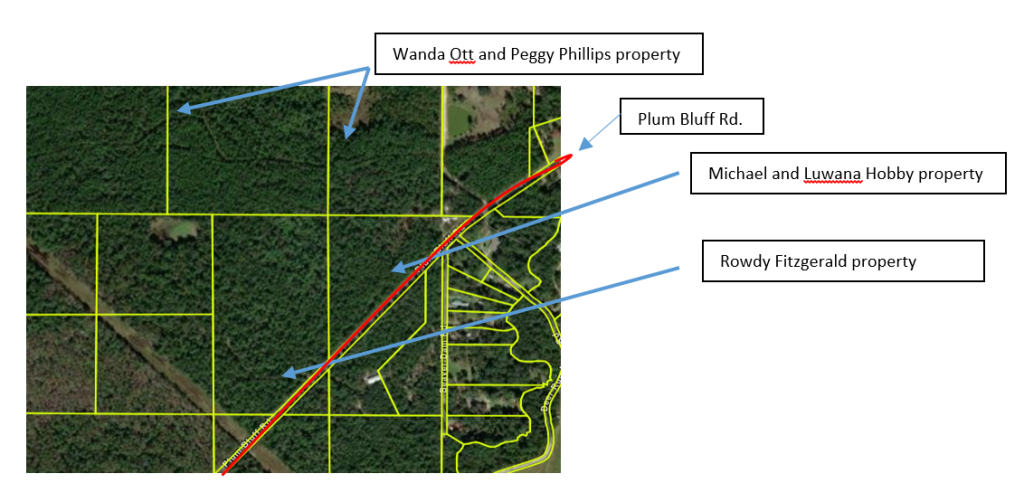

This confusion about how costs play into an easement by necessity analysis began with Hobby v. Ott, 382 So. 3d 1156 (Miss. Ct. App. 2023). In that case, E.B. Taylor owned property in George County. The property abutted a public road (Plum Bluff Road). In 1969, Taylor conveyed property that abutted Plum Bluff Road to J.R. Hobby and Betty Hobby (this property ultimately was held by Michael and Luwana Hobby). After this conveyance, Taylor retained a parcel that abutted Plum Bluff Road – and also owned the property behind the Hobbys. That meant that at the time of the conveyance, Taylor’s property still had access to a public road. Thereafter, in 1970, Taylor made three conveyances of property behind the Hobby’s, but retained the property abutting Plum Bluff Road. That meant that, at the time of the 1970 conveyances, Taylor created 3 landlocked parcels. Over time, these landlocked parcels came into the ownership of Wanda Ott and Peggy Phillips. At some point after 1970, Taylor conveyed the property he retained (and which abutted Plum Bluff Road) to Rowdy Fitzgerald. Here is screenshot of the tax parcels as of October 17, 2024 just to give a sense of how things stood at the time of the lawsuit:

According to the complaint filed by Ott and Phillips, there is a logging road across the Hobby’s property that they used to access Plum Bluff Road. At some point the Hobbys refused to allow Ott and Phillips to use the road, so Ott and Phillips sued for an easement by necessity across the Hobby’s land.

The Hobbys argued that the there were other properties which Ott and Phillips could seek to cross, so an easement across their property should be denied. One particular alternative route was over the land now owned by Rowdy Fitzgerald (the land that was retained by the original grantor Taylor after he conveyed the Hobby property). There was a 100 foot right of way given to Mississippi Electric Power Association across the property in 1972. After considering the alternatives proposed (across the Hobby land or across the Fitzgerald land), the chancellor concluded, “an easement across the Hobby’s triangular parcel of property is the most convenient and least onerous means to access the Ott and Phillips’ properties, and other alternatives would involve a disproportionate expense or inconvenience.” Therefore, the chancellor granted an easement by necessity across the Hobby’s property. The Court of Appeals reversed and rendered the chancellor’s order – holding as follows:

“Because the record reveals the existence of alternative routes, Ott and Phillips were required to provide evidence regarding the costs of accessing their properties by the alternative routes to prove that they were entitled to an easement by necessity across the Hobby properties. A thorough review of the record shows that Ott and Phillips did not provide any specific evidence of the expense involved in obtaining access by alternative routes… We find that the chancery court abused its discretion by granting Ott and Phillips an easement by necessity over the Hobby properties without evidence of the allegedly higher costs of the alternative routes.” (1163)

This evidentiary requirement – imposing on a party the obligation to show the cost of various alternative locations/properties to impose an easement — is not consistent with prior caselaw addressing the elements of an easement by necessity.

Remember, an interest in land such as an easement is subject to the statute of frauds and must be in writing to be enforceable. However, in limited circumstances a court will imply an easement as a matter of law even though there is no writing. Why? With regard to an easement by necessity the belief is that the grantor would have not have intentionally landlocked a piece of land, therefore, a court (enforcing what is the presumed intent of the parties), will impose an easement across property retained by the grantor for the benefit of the landlocked parcel.

With that justification in mind, consider the elements that a claimant must show to establish an easement by necessity: (1) easement is necessary; (2) the dominant (landlocked) and servient (parcel that easement will be placed on) estates were once part of a commonly owned parcel; (3) the implicit right-of-way arose at the time of severance from the common owner. (Hardy v. Hardy, 241 So. 3d 636, 638 (Miss. Ct. App. 2018)).

Where does the requirement that the claimant establish the cost of various means of access fit in? The Court of Appeals considers it to be under the “necessary” element: “Here, ‘[o]ur concern is only whether alternative routes exist. If none exist then the easement will be considered necessary.” (¶ 14) But cases discussing necessity do not ask a party to compare the costs to impose an easement over the property of various neighbors to determine whether an easement exists. Instead, necessity and the cost of access concerns the cost of the landowner to access a public road from their own property.

Thus in Burns v. Haynes, 913 So. 2d 424 (Miss. Ct. App. 2005), a party sought an easement by necessity across a neighbor’s property even though they could build a driveway across their own property to get to the public road. The court first (correctly) recognized that Mississippi only requires “reasonable necessity” for an easement by necessity and not “strict necessity”. [NOTE: Strict necessity was historically required for an easement by necessity – which required the claimant to have no possibility of access such that, if a party could access a public road by building a bridge they could not satisfy the necessity element.]

To determine whether there is “reasonable necessity” the court “looks to whether an alternative would involve disproportionate expense and inconvenience.” (430-31). In Burns, the claimant did not put on put on any evidence that building a new drive way would be prohibitively expensive – therefore, because the party could not establish the “necessary” element – the claim was denied. Similarly, in Hardy v. Hardy, the claimant sought an easement by necessity across his grantor’s property. The court denied the easement because there was a driveway that provided access to a public road. The claimant argued that the public access point was “one-half mile farther north and only provided access to his property and not to his home place…” and that the route was not passable because it was overgrown. The court held that the test is not whether it would be more convenient to have a different location of access, there must be a showing of necessity to justify the grant of an implied easement across the grantor’s land.

Classic cases where there is reasonable “necessity” involve where the claimant would have to build a bridge on their property to reach a public road. Mississippi Power v. Fairchild, 791 So. 2d 262 (Miss. Ct. App. 2001); Rotenberry v. Renfro, 214 So. 2d 275, 278 (Miss. 1968)).

These cases put the burden on the party claiming an easement by necessity to show that the alternative route across their own property is cost prohibitive so they are entitled to an easement across their grantor’s property.

In Hobby v. Orr, the court of appeals (I think because of the nature of the arguments presented by the parties), misapplied how the element of “necessity” . The question is not the expense to impose an easement across one neighbor’s property as opposed to other routes. The question is whether, assuming the landowner has access to a public road, can they demonstrate that it would be so expensive to use that access that it would be unreasonable to use that route to gain access to a public road.

So, how should Hobby v. Orr have been decided? Although the facts are somewhat convoluted, it seems clear that at the time that Taylor conveyed Hobby his parcel first (in 1969), Taylor retained property with access to Plum Bluff Road and it was not until later (1970) when he conveyed property to the predecessors of Ott and Phillips that those parcels were landlocked. Therefore, if an easement by necessity is available (which there is a strong argument that there is), then it should be imposed across the land that was retained by the grantor at the time the lots were landlocked (property now owned by Rowdy Fitzgerald) and not over the Hobby’s land (regardless of whether it would be more convenient or cost effective to cross the Hobby’s land).

The unfortunate legacy of Hobby v. Orr

Now, getting back to Word v. U.S. Bank. In my opinion, the second section of the opinion titled: “U.S. Bank presented no evidence regarding the costs of using an available alternative route to access its property” simply should have been omitted. It was unnecessary to the holding and furthers the incorrect analysis in Hobby v. Orr. There was no evidence that U.S. Bank had access to a public road across its own property, therefore, there was no need to consider the cost of access.

The court does note that there is a statutory mechanism for obtaining an easement for a landlocked parcel which could be obtained over property of someone other than the grantor. Miss. Code Ann. 65-7-201 provides that when someone wants a private road over the land of another they shall utilize an eminent domain proceeding. Under this statute, if a right-of-way is granted, the servient property owner is entitled to compensation for the property interest that was lost. This is a very important point — when an easement is implied by necessity, the servient property owner is not entitled to compensation because the easement is imposed based on the presumed intent of the parties at the time of the conveyance. That is why it critically important that easements by necessity only be granted across the land of the grantor that created the landlocked parcel.

Final thoughts: Hopefully in a future case the appellate courts will clarify the “reasonable necessity” element (and hopefully move away from the Hobby analysis).

Leave a comment