Keeping the faith – state of mind in an adverse possession case

September 27, 2024 § 1 Comment

By: Donald Campbell

Signaigo v. Grinstead, 2024 WL 2284923 (Miss. Ct. App. 2024)

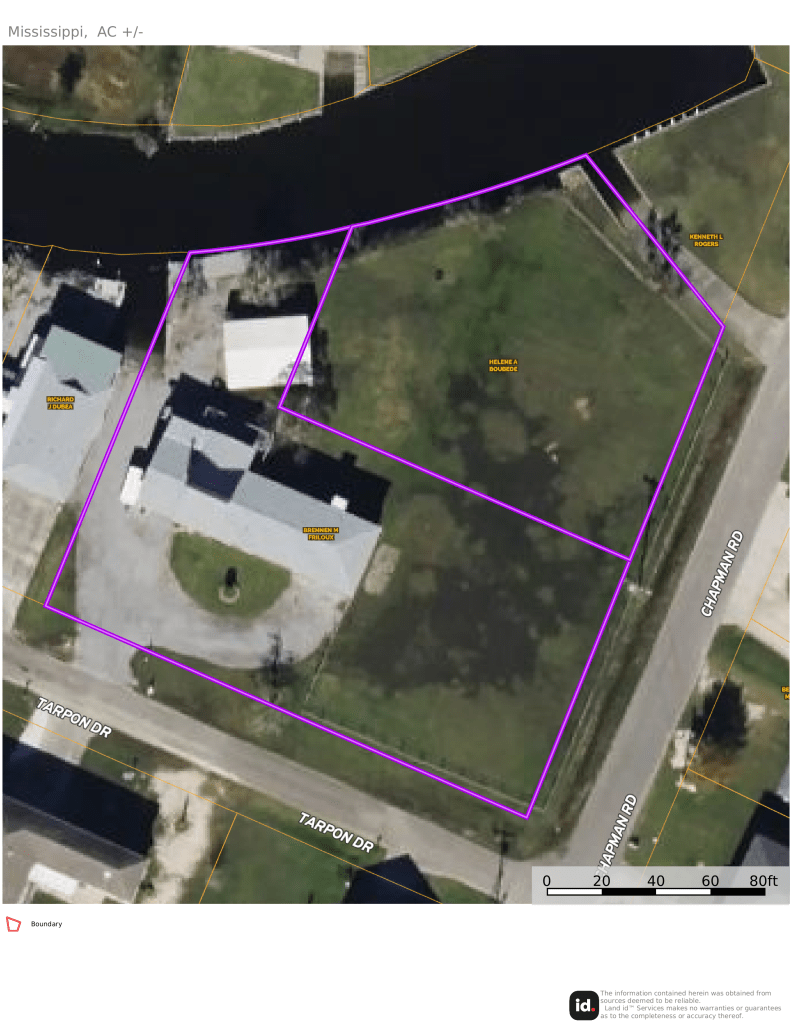

William and Judith Signaigo purchased property in Shorelines Estates in Hancock County in 1997. The adjacent property was owned by Helene A. Boubede at that time. Boubede lived in Iowa and, when she died, the property went to her daughter Myrna Grinstead.

After moving onto the property, the Signaigos fenced in part of their property and all of the Boubede property. When asked if she gave any thought as to whether they were fencing in someone else’s property, Mrs. Signaigo testified: “No. The only thing I was concerned about was the fact that there’s water here and there is a street there and the dogs were bringing stuff back from other places and we wanted to fence it in.” She also testified that she and her husband knew that the property was not theirs. In fact, they tried to contact Ms. Boubede about purchasing the property but were not able to get in contact with her. Beginning in 1997, the Signaigos performed all upkeep on the disputed property: mowing the grass, removing debris following hurricanes, removing trees, and providing fill material.

On September 15, 2021, the Signaigos filed a lawsuit against Boubede/Grinstead claiming ownership of the property by adverse possession. The case was assigned to Chancellor Margaret Alfonso. After a hearing, the chancellor found that adverse possession had not been established because the the Signaigos did not establish: (1) claim of ownership of the property; or (2) open and notorious possession. Signaigos appealed and the case was assigned to the Court of Appeals.

Judges Barnes, Greenlee, and McCarty were on the panel that heard the case. Judge Greenlee, writing for a unanimous court, affirmed Chancellor Alphonso.

To establish a claim of ownership by adverse possession in Mississippi the adverse possessor must satisfy the following six elements for 10 years (see Miss. Code Ann. 15-1-13): (1) under claim of ownership; (2) actual or hostile; (3) open, notorious, and visible; (4) continuous and uninterrupted for 10 years; (5) exclusive; and (6) peaceful.

The dispositive issue was whether there was a “claim of ownership.” There have been a split of decisions in Mississippi when it comes to what it means to claim ownership. Some older cases have said that the key to a claim of ownership is the taking of steps demonstrating that the adverse possessor is making a claim to the property. Therefore, the determining factor was what the adverse possessor did to possess the property — not the state of mind of the adverse possessor. For example, in 1846, the High Court of Errors and Appeals of Mississippi held: “There is no doubt, that the possession of a mere intruder, is protected to the extent of his actual occupation; whilst one who has color of title is protected to the extent of the limits of his title.” (Grafton v. Grafton, 16 Miss. 77, 91 (Miss. 1846)). Again, in Levy v. Campbell in 1946, the court notes that, as far back as 1858: “it has been settled rule in this state that although the possession may have been begun by a mere intruder without any color of title at all, the occupant may establish title by adverse possession to the extent of his actual occupation.” In short — it does not matter that the adverse possessor knows that they are trespassing so long as they actually take possession.

A 2004 Mississippi Supreme Court case (Blackburn v. Wong, 904 So. 2d 134 (Miss. 2004)) rejected the idea that possession is all that matters and required the adverse possessor to be acting in good faith. “Good faith” means that the adverse possessor must have a reasonable belief that they have rights in the property. In Blackburn a lawyer built a law office onto the property of another. Shortly after the building was constructed, a surveyor informed the lawyer that his office was across the property line. At that point the lawyer testified he had three options: (1) contact the true owner to try to purchase the property; (2) dig up the sewer lines and tear down the building; or (3) wait for the adverse possession time to pass and claim ownership. The lawyer chose to wait out the time for adverse possession. The lawyer possessed the property from 1971 through 1999 (when the suit commenced). The court, without much analysis held that, because the lawyer found out that he did not own the disputed strip shortly after the building was completed, he could not claim the property by adverse possession.

Relying on the Blackburn holding, the court in Signaigo held that, because the Signaigos knew that they did not own the property at the time they went into possession, they could not establish the element of “claim of ownership”. Therefore, the heirs of Boubede own the disputed parcels. The court remands the case for a determination of heirship.

Professor Thoughts

The justification of allowing adverse possession is to ensure that property is used and not abandoned by an absentee owner without any hope of putting the property back into use. To this end, there are three approaches that states have taken to determine whether an adverse possessor can demonstrate a “claim of title”: (a) good faith; (b) bad faith; and (c) objective approach (state of mind is irrelevant).

The majority of states take the approach that the state of mind is irrelevant. The rationale for taking this approach is two-fold: (1) if the justification of adverse possession is to reward the industrious possessor and punish the true owner who has not bothered to check on their property for more than 10 years — whether the adverse possessor knew the property was not theirs or whether they had a reasonable belief it was, is irrelevant; and (2) requiring testimony of a state of mind can encourage adverse possessors to lie on the stand to conform their testimony to what is required in the jurisdiction. Those older Mississippi cases followed this approach — emphasizing the possession over the state of mind. In adopting the objective approach (and abandoning the good faith approach), the Washington Supreme Court noted: “The doctrine of adverse possession was formulated at law for the purpose of, among others, assuring maximum utilization of land, encouraging the rejection of stale claims and, most importantly, quieting titles… Because the doctrine was formulated at law and not at equity, it was originally intended to protect both those who knowingly appropriated the land of others and those who honestly entered and held possession in full belief that the land was their own… Thus, when the original purpose of the adverse possession doctrine is considered, it becomes apparent that the claimant’s motive in possessing the land is irrelevant and no inquiry should be made into his guilt or innocence.” (Chaplin v. Sanders, 676 P.2d 431, 435 (Wash. 1984)(en banc))

Some states (after Wong, Mississippi is in this category) require that the adverse possessor act in good faith (have a reasonable belief that they own the property to satisfy the claim of ownership requirement). The justification for this approach (and this is apparent in both the Wong and Signaigo case) is the refusal to reward land pirates (ie intentional trespassers). Under this approach, it does not matter that the Signaigos put the property to use from 1997 until 2021 or that Blackburn had his law office on the property from 1971 until 1999 — the fact that they were using the property knowing it was not theirs, defeated their claim.

The final approach, bad faith, is only followed by one state that I am aware of — Arkansas (Fulkerson v. Van Buren, 961 S.W. 2d 780 (Ark. Ct. App. 1998)) Under this approach, to satisfy the “claim of ownership” element, the adverse possessor must be able to show that they knew that the property was not theirs and they intended to claim it as their own. The rationale is that someone should not be able to gain title (and the owner should not lose title) by accident. To claim title by adverse possession, the possessor must intend to do so.

The bottom line: in an adverse possession case, the adverse possessor must be able to demonstrate by clear and convincing evidence that they had a good faith belief they had a right to the disputed property. This should not be a problem in a run-of-the-mill boundary line dispute case where the parties genuinely did not know about the encroachment until it is revealed years later (for example Conliff v. Hudson, 60 So. 3d 203 (Miss. Ct. App. 2011)). However, a client who has long possessed the property and either knows they have no ownership interest in the property or learn, before the 10 years runs, that they are not the owner of the property, will not be able to establish the “claim of title” element of adverse possession.

Posthumously Conceived children

September 24, 2024 § 1 Comment

With advances in technology, babies can now be created without sexual intercourse. The use of assisted reproductive technology has been increasing. In 2021, 2.3% of infants born in the United States were conceived with assisted reproductive technology. Under traditional law, if a child was not in utero at the time of the parent’s death – they were not considered the child of the deceased. Today, however, a deceased person can be the biological parent of a child long after their death.

Children conceived by assisted reproductive technology raise unique challenges for the traditional inheritance system. First, the parent who predeceased before the child was conceived may have no knowledge that their biological material would be used to assist in reproduction, and therefore may not want the after born child to have a share of their estate. Second, any inheritance that is provided for the child will diminish the amount that is taken by children who were born or conceived prior to the parent’s death, and could disrupt the orderly administration of the estate if there are no limitations on how long after the parent’s death a child can be conceived.

The issue is how to balance the competing concerns between the innocent child, the deceased’s interest in controlling where their property goes, and the efficient administration of estates. It should be noted that the outcome impacts issues beyond the inheritance system itself. Survivorship rights are often determined by whether the person has the right to inherit under a state’s descent and distribution law. The Social Security Administration considers a posthumously conceived child as a non-marital child who is only entitled to benefits if they are entitled to inheritance rights under state intestacy law.

In 2024, Mississippi adopted House Bill 1542 that sets out the rights of children conceived by assisted reproductive technology (methods of conception without sexual intercourse). The law provides that children born through assisted reproductive technology can inherit a child’s share of the deceased parent’s personal property if certain procedures are followed. The law is tilted the Chris McDill law in memory of Chris McDill. McDill was diagnosed with cancer and he and his wife Katie were unable to conceive before his death. Katie subsequently had a child through IVF, but was not able to claim survivor benefits through the Social Security Administration because the child was not entitled to inherit under Mississippi law.

First, the parent must have died without disposing of all of their personal property. Therefore, a posthumously conceived child’s rights are solely in personal – not real – property. Furthermore, if the deceased has disposed of all of their personal property in a will to someone other than the posthumously conceived child – the subsequently born child is not entitled to inherit.

Next, there must be a document signed by the deceased parent and the person that is planning on using the genetic material that the now-deceased parent consented to the use of genetic material in assisted technology after their death. The requirement that there be a record of consent from the deceased parent is to recognize and respect the reproductive desires of the deceased.

After death, the personal representative and the court must have been given notice or had actual knowledge of the intent to use genetic material in assisted reproduction not later than six months after the death of the parent. Thereafter, the embryo must be in utero not more than thirty-six months after the parent’s death, and the child must be born not later than forty-five months after the parent’s death and must live 120 hours after birth. The purpose of setting this time frame is to give the surviving parent an opportunity to grieve and contemplate whether to use the genetic material while, at the same time, ensuring that the estate will not remain open indefinitely.

If the deceased was divorced or legally separated from the individual seeking to use the genetic material, there is a rebuttable presumption that the decedent did not consent to use of their genetic material in assisted reproductive technology.

If the requirements above are satisfied, the court shall set aside a child’s share of the qualifying personal property. Each qualifying child would share in that child’s share of the estate. The court should then distribute the remainder of the estate as provided by law of descent and distribution and close the estate for all purposes except distribution of the set-aside property. Once the eligible children (born and survive 120 hours) are ascertained, the court should distribute the set-aside property to those children. If there are no eligible children, the court should distribute the estate according the descent and distribution statute. The statute expressly provides that it is the intent of the law that “an individual deemed to be living at the time of the decedent’s death” under the statute would qualify for federal survivor benefits.

Your eyes are not deceiving you

September 20, 2024 § 27 Comments

My name is Donald Campbell. I am a professor at Mississippi College School of Law where I teach in the areas of Property, Wills & Trusts, and legal ethics. When I first started teaching Wills a colleague told me that I had to subscribe to Judge Primeaux’s blog. I did, and thereafter I looked forward to every post that he made. And it was not just me. There is no doubt that Judge Primeaux’s blog was a go-to for all things chancery (and beyond) for years. When Judge Primeaux decided to step away from blogging it was a loss for the profession.

I am excited to announce that with the judge’s blessing, I am hoping to bring back a version of Better Chancery Blog. The focus will still be on issues/cases that arise in chancery court. Of course the problem is that I can never produce the “my thoughts” comments that pulled back the curtain on how a judge thinks. I am hoping that, through the comments members of the bar and bench can engage in a discussion of how these issues arise in practice.

Although I realize I am burying the lead, I am truly honored to have Dean Debbie Bell as a contributor to the blog on family law issues. Dean Bell needs no introduction. Her book (Bell on Mississippi Family Law) is a well-respected and often-cited treatise on family law in Mississippi. I am excited to see the insight that Dean Bell will bring to the blog.

To give you a sense of how the blog will operate going forward, I hope to post twice a week. A post on Tuesday that covers a recent issue or case. Then a post on Friday that looks at a case or issue that may not be directly related to current issues in Mississippi law. If there are any suggestions on improving the blog as we move forward, please to not hesitate to reach out.